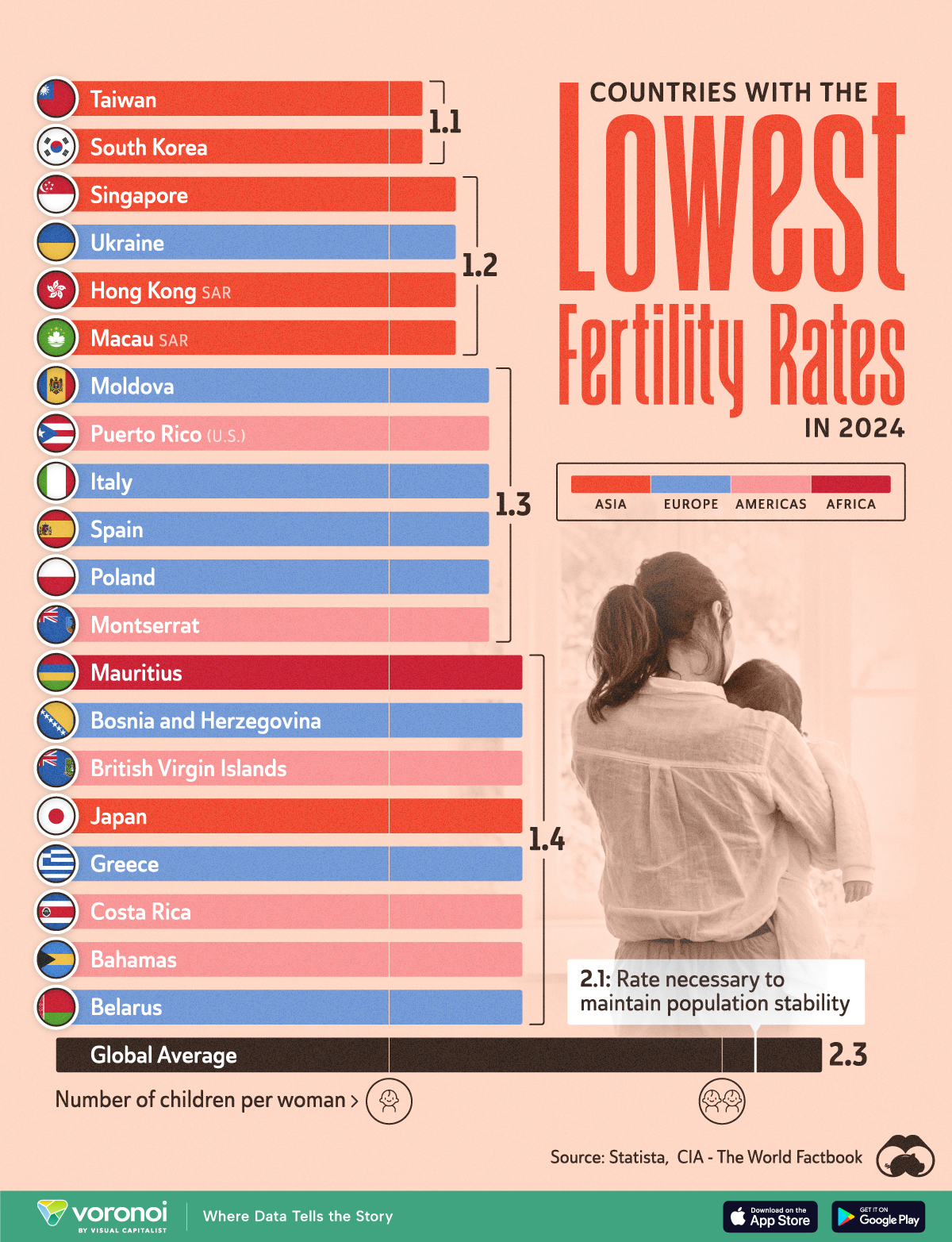

Japan has been trying to boost its fertility rate for 30 years. Now the rest of the rich world is, too.

In 1989, Japan seemed to be an unstoppable economic superpower. Its companies were overtaking competitors and gobbling up American icons like Rockefeller Center. But inside the country, the government had identified a looming, slow-motion crisis: The fertility rate had fallen to a record low. Policymakers called it the “1.57 shock,” citing the projected average number of children that women would have over their childbearing years.

If births continued to decline, they warned, the consequences would be disastrous. Taxes would rise or social security coffers would shrink. Japanese children would lack sufficient peer interaction. Society would lose its vitality as the supply of young workers dwindled. It was time to act.

Starting in the 1990s, Japan began rolling out policies and pronouncements designed to spur people to have more babies. The government required employers to offer child care leave of up to a year, opened more subsidized day care slots, exhorted men to do housework and take paternity leave, and called on companies to shorten work hours. In 1992, the government started paying direct cash allowances for having even one child (earlier, they had started with the third child), and bimonthly payments for all children were later introduced.

None of this has worked. Last year, Japan’s fertility rate stood at 1.2. In Tokyo, the rate is now less than one. The number of babies born in Japan last year fell to the lowest level since the government started collecting statistics in 1899.

Now the rest of the developed world is looking more and more like Japan. According to a report issued in 2019 by the United Nations Population Fund, half of the world’s population lives in countries where the fertility rate has fallen below the “replacement rate” of 2.1 births per woman.

Why should countries care about shrinking populations at a time of climate change, increasing risk of nuclear catastrophe and the prospect of artificial intelligence taking over jobs? At a global level, there is no shortage of people. But drastically low birthrates can lead to problems in individual countries.

Tomáš Sobotka, one of the authors of the U.N. report and a deputy director at the Vienna Institute of Demography, does a back-of-the-envelope calculation to illustrate the point: In South Korea, which has the lowest birthrate in the world at 0.72 children per woman, just over a million babies were born in 1970. Last year, 230,000 were. It’s obviously too simple to say that each person born in 2023 will, in their prime working years, have to support four retired people. But in the absence of large-scale immigration, the matter will be “extremely difficult to organize and deal with for Korean society,” said Mr. Sobotka.

Similar concerns arise from Italy to the United States: working-age populations outnumbered by the elderly; towns emptying out; important jobs unfilled; business innovation faltering. Immigration could be a straightforward antidote, but in many of the countries with declining birthrates, accepting large numbers of immigrants has become politically toxic.

How a Vast Demographic Shift Will Reshape the World

The most powerful countries have benefited from large work forces for decades. What happens when they retire?

Across Europe, East Asia and North America, many governments are, like Japan, introducing measures like paid parental leave, child care subsidies and direct cash transfers. According to the U.N., the number of countries deliberately targeting birthrates rose from 19 in 1986 to 55 by 2015.

The topic has surfaced in the American presidential campaign, with the Republican vice-presidential candidate, JD Vance, chastising the country for its low birthrates and defending his past comments about “childless cat ladies” running the nation. Mr. Vance has suggested raising the child tax credit and said he would consider a policy, like one in Hungary, in which women with multiple children are taxed at a lower rate. On the Democratic side, Kamala Harris has proposed a $6,000 tax credit for families with infants. While Ms. Harris doesn’t present this as a pro-fertility policy, it echoes what other countries are doing.

More in Asia Pacific

//So, Are You Pregnant Yet? China’s In-Your-Face Push for More Babies.Oct. 8, 2024 https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/08/worl ... tions.html

Advocates sometimes suggest that if you offer paid family leave or free day care, birthrates will magically shoot up. But for some 30 years Japan has been a kind of laboratory for these initiatives — and research shows that even generous policies yield only slight upticks.

After years of political grandstanding and a growing menu of government initiatives, modern families just don’t seem to want to grow larger. “The policies would need to be very, very coercive to push people to change their preferences,” Mr. Sobotka said. “Or to have kids they didn’t want or plan to have.” So what kinds of measures might actually induce people to have more babies? And if nothing really works, why not?

The Great Baby Bust

There’s plenty of evidence that governments can change fertility rates, but generally in one direction: down.

In East Asia, many of the countries that now have exceedingly low fertility initially imposed it on themselves. For more than three decades, China enforced a one-child policy. After World War II, Japan encouraged the wide use of contraception and decriminalized abortion in an effort to shrink the population. Likewise, in South Korea, the government legalized abortion in the early 1970s and discouraged families from having more than two children.

Minchul Yum, an associate professor of economics at Virginia Commonwealth University who has studied South Korean birthrates, said his mother told him that “if you brought more than two kids onto public transportation, it was like a social stigma.”

In Europe and the United States, fertility rates declined as more women entered the work force and the influence of religion — particularly Catholicism — receded. Young people, who started to leave the communities where they were raised, pursue careers and build networks that normalized postponing marriage, had fewer children as they started childbearing later.

Lower birthrates signify progress: Declining infant mortality rates reduced the need to have many children. As economies transitioned away from predominantly agricultural or family-owned businesses that required offspring to run, people focused on leisure and other aspirations. Women could now pursue career goals and personal fulfillment beyond raising children. Undergirding it all was the rise of birth control, which meant women could determine whether and when they got pregnant.

But the impediments to having multiple children have also grown. Housing costs are ballooning and the gig economy has made young people worry about their own — and their potential offspring’s — financial security. The cost of educating children and preparing them for a more competitive and inequitable job market keeps increasing. The kinds of institutions that once helped people meet future partners with whom they might want to have children, such as the church or formal matchmaking services, have waned.

As families have fewer children, they invest more in those they have. Parents in China, Japan and South Korea compete to enroll their children in the best schools and pay for rigorous tutoring from a very young age. Some of those practices have become familiar in the United States, too. In August, Vivek H. Murthy, the surgeon general, issued an advisory to call attention to rising levels of stress and mental health concerns among American parents.

Children no longer provide direct economic value with their labor, or an insurance policy in the way that in previous generations it was virtually guaranteed that children would take care of their parents in old age, according to Poh Lin Tan, a senior research fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies in Singapore. “We are at the place where having children is really a matter of pure joy and a preference where you kind of have to pay for and make some sacrifices in terms of your leisure and career advancement,” Tan said.

Better Dads, More Babies?

Despite changes in family and work life, traditional ideas about who should take care of children — women, of course — have proved resistant to policy prescriptions. “Cultural expectations are designed to fit a way of living that doesn’t exist anymore,” said Matthias Doepke, an economist at the London School of Economics. “That is the root cause of these extremely low fertility rates that we have in rich countries.”

In Japan, a demanding work culture that originated in an era when many women stayed home makes it difficult to balance career and family. Despite some changes, employees are still expected to put in long hours, socialize with colleagues or clients at night and travel frequently for business. More than in the West, Japanese mothers, even those with careers, take care of the majority of child care and housework.

Kumiko Nemoto, a sociologist and gender scholar at Senshu University in Tokyo, interviewed 28 Japanese women in executive or managerial positions. Many did not have children. Those who did either relied heavily on their parents or paid as much as $2,000 a month for child care. “Almost all of these women said their husbands did not help them,” Ms. Nemoto said.

Some governments on the other side of the world have tried to address these kinds of inequalities. Scandinavian countries have enacted policies to shift some of the burden onto men in the hope that they can support bigger families.

In 1995, Sweden introduced what came to be known as the “daddy month,” a month of parental leave given to the spouse — usually the father — who had not already taken leave after the birth of a child. If that spouse did not use the month, the couple would lose it. With the addition of second and third “use it or lose it” months in subsequent years, more fathers took paternity leave. “That has created a change in cultural expectations on what it means to be a good father,” said Ylva Moberg, a researcher in economics and sociology at Stockholm University.

Yet fertility rates in Sweden have not increased. Economists say it’s not clear that that means the policy has failed, given that Sweden’s rates are higher than those in East Asia. “The problem for economists is that even if the fertility rates haven’t gone up, they could have gone down more,” said Anna Raute, an associate professor of economics at Queen Mary University of London.

Some conservatives and religious scholars suggest that rather than encourage fathers to do more, governments should incentivize women to quit work to raise children. But even countries like Finland and Hungary that provide generous benefits, such as letting a parent take up to two or three years off after a child is born, have not seen significant increases in their fertility rates.

Marriage, or Something More Fundamental

If more gender equality between parents, tax rebates and cash allowances can’t create bigger families, what else can a desperate government do?

In Japan, policymakers are trying a new gambit: promoting weddings. Last year, fewer than 500,000 couples got married in Japan, the lowest number since 1933, despite polls showing that most single men and women would like to do so. One obstacle is that many young adults live with their parents — close to 40 percent of people aged 20 to 39, according to data from 2016, the latest year for which it is available. “Living with your mom is not the best romantic environment for finding your lifelong partner,” said Lyman Stone, director of the Pro-Natalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies in Charlottesville, Va.

Japanese politicians have also talked about the importance of raising wages, and some economists say the government should support corporate social activities that could lead to relationships. L.G.B.T.Q. advocates argue that Japan should legalize same-sex marriage and help such couples have children.

The Tokyo government recently launched its own dating app, but it has not released any enrollment figures. On social media, the initiative seems to have gotten more attention from Elon Musk than from local residents.

It’s hard to imagine that this pro-wedding push will succeed in boosting the birthrate any more than Japan’s last three decades of initiatives have. In the end, it seems that governments can only do so much.

In China, intrusive efforts by the authoritarian government to encourage childbearing have generated a backlash. In democratic countries, policies with a whiff of a mandate will likely engender fierce opposition, too. The truth is that a decision as momentous as whether to have children rarely comes down to mere economics or who will change the diapers.

Influencing those choices may be beyond the reach of traditional government policy. For most people in affluent countries, having children is deeply personal, touching on our values, what kinds of communities we want to be part of, how we view the future. Sometimes it’s also about luck. “Policies cannot find you the best possible partner you dreamed of at the right time,” Mr. Sobotka pointed out.

That’s not to say that some of the policies implemented to spur higher birthrates, or at least partly for that reason, are not meaningful. Providing high-quality, subsidized child care, motivating fathers to take part in their children’s lives and refashioning the workplace to let employees engage with their families can all help improve the lives of those who do have children.

Here in Tokyo, friends with young children rave about the wonderful, affordable nursery schools where children from early infancy to as old as 5 eat nutritional lunches and caregivers send daily photos and personalized updates. Compared to when I was here as a newspaper intern in the late 1980s, I see more fathers taking their children on the subways and to playgrounds on weekends.

Still, it’s hard to escape the feeling that old people far outnumber babies. And I’ll tell you what I see more frequently than parents walking with toddlers: adults with their dogs dressed in sweaters and bootees, toting them in carriers strapped to their chests or pushing them in strollers.

Kiuko Notoya contributed reporting.

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/13/worl ... 778d3e6de3