Miscellaneous Articles on Ginans

Honoring Zawahir Moir:

Catalogue of 114 Khojki Manuscripts in Searchable Form

Ali Jan Damani

(Institute of Business Administration)

Brief note:

Zawahir Noorally (now, Zawahir Moir) prepared a catalogue of 114 Khojki manuscripts in 1971. The manuscripts catalogued by her were then under the custody of the Ismailia Association for Pakistan (now; ITREB, Pakistan). Unfortunately, the catalogue remained in the scanned form with some scholars and no efforts were made to re-type and arrange the catalogue in searchable form. Hence, this is the pioneer effort by Ali Jan Damani to

re-type the catalogue in searchable form. Mistakes, errors and inconsistencies of all types are maintained as they appear in the original catalogue. This work was undertaken by Ali Jan Damani while he was studying the catalogue critically for his forthcoming article on the project of how the khojki manuscripts must be subject to cataloguing by potential scholars.

pdf file at:

ismailimail.files.wordpress.com/2020/08/zawahir-catalogue__searchable__damani.pdf

Catalogue of 114 Khojki Manuscripts in Searchable Form

Ali Jan Damani

(Institute of Business Administration)

Brief note:

Zawahir Noorally (now, Zawahir Moir) prepared a catalogue of 114 Khojki manuscripts in 1971. The manuscripts catalogued by her were then under the custody of the Ismailia Association for Pakistan (now; ITREB, Pakistan). Unfortunately, the catalogue remained in the scanned form with some scholars and no efforts were made to re-type and arrange the catalogue in searchable form. Hence, this is the pioneer effort by Ali Jan Damani to

re-type the catalogue in searchable form. Mistakes, errors and inconsistencies of all types are maintained as they appear in the original catalogue. This work was undertaken by Ali Jan Damani while he was studying the catalogue critically for his forthcoming article on the project of how the khojki manuscripts must be subject to cataloguing by potential scholars.

pdf file at:

ismailimail.files.wordpress.com/2020/08/zawahir-catalogue__searchable__damani.pdf

Pirs composed Ginans to teach Ismaili doctrines

Posted by Nimira Dewji

Ginan bolore nit nure bharea;

evo haide tamare harakh na maeji.

Recite continually the Ginans which are filled with light;

boundless will be the joy in your heart. (tr. Ali Asani). Listen

Ginans are a vast collection comprising several hundred poetic compositions which have been a central part of the religious life of the Nizari Ismaili community of the Indian subcontinent that today resides in many countries around the world. Derived from the Sanskrit gyan, meaning contemplative knowledge, Ginans refer to the poetic compositions authored by Ismaili Pirs, who came to the Indian subcontinent in the eleventh century to teach the Ismaili interpretation of Islam. The literature is also shared by the Imamshahi community in Gujarat, who are believed to have split off from the Nizari Ismailis in the sixteenth century (IIS)

At the time, the field of devotional poetry was flourishing, with figures such as Narasimha Maeta (15th century), Mirabai (1498-1557), Narhari (17th century), Kabir (1440-1518), Guru Nanak (1469-1539), among others. A tradition of mystical poetry was also developing among the Sufis in the subcontinent. The Pirs used the subcontinent’s many languages, folk songs, myths, and traditional music to articulate its core concepts” (Asani, A Modern History of the Ismailis p 96). Compositions were also influenced by the various communities’ needs to assimilate the practices of the dominant local populace in order to avoid persecution.

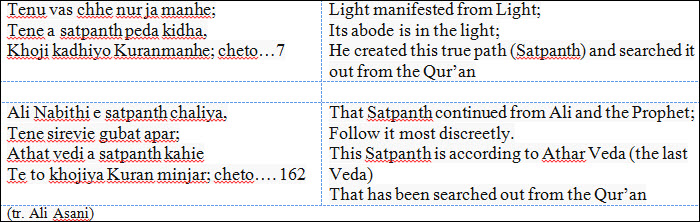

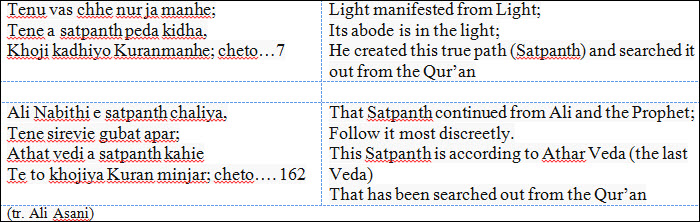

The form of Nizari Ismail tradition in the subcontinent came to be known as sat panth (‘true path’). The term panth, “an Indic term meaning path, doctrine or sect, is popularly used in the names of groups that crystallized around the different religious personalities of medieval India. For example, followers of the poet Dadu call their movement Dadupanth while those of Kabir use the term Kabirpanth. The term satpanth used by the Ismaili pirs echoes the Qur’anic concept of sirat al-mustaqim (the right path).

Through the medium of Ginans, the Pirs provided guidance on a variety of doctrinal, ethical, and mystical themes for the community while also serving to explain the inner meaning (batin) of the Qur’an to the external (zahir) aspects. The Ginan literature “came to be perceived within the community as a kind of commentary on the Qur’an. Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah explained “In the ginans which Pir Sadardin has composed for you, he has explained the gist of the Qur’an in the language of Hindustan” (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 30).

“According to Paul Walker, the Ismailis have:

tolerated a surprising intellectual flexibility and leeway. That in turn has allowed men of various philosophical temperaments to enter into and promote with enthusiasm this particular kind of Islam… This fact may explain why the Ismaili movement attracted a number of brilliant and creative thinkers and also why others of equal brilliance seem to lean in their direction.”

Cited in Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 7

Language of Ginans

Ginans were composed in Punjabi, Multani (Saraiki), Sindhi, Kachhi, Hindustani/ Hindi, and Gujarati. Compositions were also influenced by the various communities’ needs to assimilate the practices of the dominant local populace in order to avoid persecution.

The specific form of Nizari Ismaili interpretation came to be known by the translation of sirat al-mustaqim, rendered as Satpanth (sat panth, or ‘true path.’)

Themes

The number of verses in Ginans varies from four to ten in the shorter ones to over five-hundred in the longer ones. Generally the shorter versions do not possess titles, therefore, the first verses or refrains serve as titles for identification purpose. Longer Ginans designated as Granths, have titles that may reflect the main theme or message such as the Bujh Niranjan (Knowledge of the Attributeless Deity), a long mystical poem on the spiritual quest of the soul; Soh Kiriya (One-Hundred Obligatory Acts) provides instruction for proper conduct.

Several Ginans are stories or parables that are meant to be interpreted mystically such as Kesri sinh swarup bhulayo (The Lion Forgot his Lion-form), which describes a lion who has forgotten its true identity on account of its upbringing among a flock of sheep. Listen

Many Ginans are supplications (venti) for spiritual enlightenment and vision (darshan, didar) such as Hun re piasi tere darshan ki (I Thirst for a Vision of You), which draws on the symbol of a fish writhing in agony outside its home in water. Listen

Unch thi ayo (Coming From an Exalted Place) is a lament of the soul’s fate in the material world and a plea for the intercession of Prophet Muhammad. Listen

Music

The Ginans were a counterpart to the traditions of the geet, bhajan, and kirtan among the many traditions prevalent in the subcontinent. Like most Indian devotional poetry, Ginans are meant to be sung. Music, therefore, is a vital characteristic of Ginans to invoke specific emotional states such as on special occasions, morning prayers, evening prayers, ghatpat ceremony, or at funerals. Each Ginan is distinguished by its raga, or musical mode, with the name of the composer at the end, a characteristic of North Indian poetry. If a Ginan does not possess a refrain, the first verse is used as refrain, a common practice in the Bhakti and Sant traditions of the subcontinent.

Furthermore, Ginans are meant to be sung from memory and heart rather than from a script in order to eliminate the intermediary (the book) between worshipper and the Divine. To compensate the differences between the poetic and musical metre of a ginan, extra syllables such as ‘re’ and ‘eji’ are often inserted during recitation (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment, p 52, n 50).

Although initially an oral tradition, Ginans were recorded in Khojki, a special script adopted by the Ismaili community of the Indian subcontinent primarily to record the community’s religious literature.

Pir Satgur Nur (d.1094) was the earliest Pir sent to the subcontinent. Nanji states that “Satgur Nur came to Jambu-dvipu from Sahetar-dvipa via the city of Bhildi and proceeded to Patan in Gujarat” (Listen).

The term jambu-dvipa refers to “the land of the jambu tress,” jambu being the name of the species of Jambul (Syzgium cumini of the myrtle family Myrtaceae) or Indian blackberries, dvipa meaning ‘island’ or ‘continent.’ The jambu trees were native to the Indian subcontinent as well as other areas of South Asia and Australia, although subsequently grown in other tropical climates around the world. The trees were considered sacred to Lord Krishna and therefore planted close to Hindu temples.

Pir Satgur Nur was followed by Pir Shams al-Din, who was active in the mid-fourteenth century, mainly in Uchchh and Multan in the province of Sind, and associated with Imam Qasim Shah (r. ca. 1310-1370). Pir Shams is also featured prominently in a number of Sufi traditions.

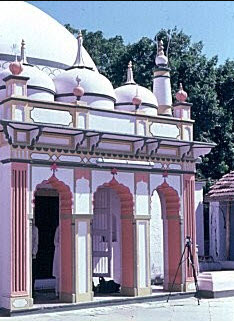

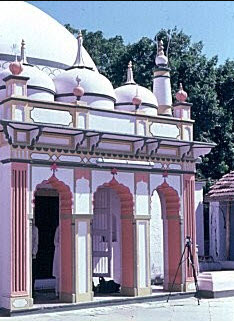

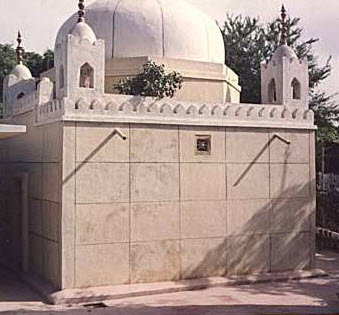

Satgur Nur pir

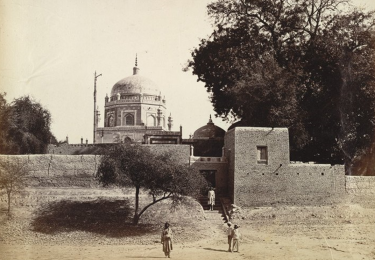

Pir Satgur Nur’s Mausoleum. Source: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Garbis

Very popular during the Gujarati culture of western India was the garbi, a folk dance in which individuals move around in a circle and sing to the accompaniment of a rhythmic clap of hands and feet. “the dancers in motion, as well as the songs composed for the occasion are known as garbis” (Nanji, The Nizari Ismaili Tradition p 20)

Pir Shams, who is said to have joined in the dancing of the Hindu festival of Navratri, substituted his own words for theirs, thus teaching them the principles of Ismailism. Pir Shams composed 28 garbis. Listen to the garbi titled Evi garbi sampuran saar.

Pir Sadr al-Din

Pir Shams was succeeded by his son Nasir al-Din and grandson Shihab or Sahib al-Din, both conducting activities in secrecy to avoid persecution. The latter was succeeded by Pir Sadr al-Din, who worked during the time of Imam Islam Shah (r. 1369/70 to 1425/26), and is considered the founder of the Nizari Ismaili Khoja community.

Pir Sadr al-Din played a prominent role in converting many Hindus, giving them the Persian title of khwaja (meaning ‘master’), corresponding to the Hindu title of thakur. He is credited with authoring the largest number of Ginans, and establishing the earliest jamatkhanas in Kotri, Sind in the fifteenth century, with additional ones in Panjab and Kashmir.

Pir Sadr al-Din died between 1369 and 1416; he was succeeded by Pir Hasan Kabir al-Din, (d. ca. 1470) and Pir Taj al-Din (d. end of the 15th century).

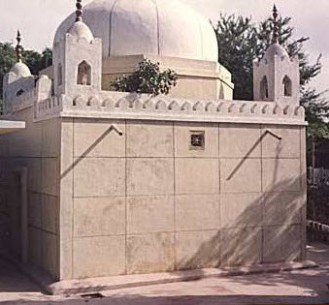

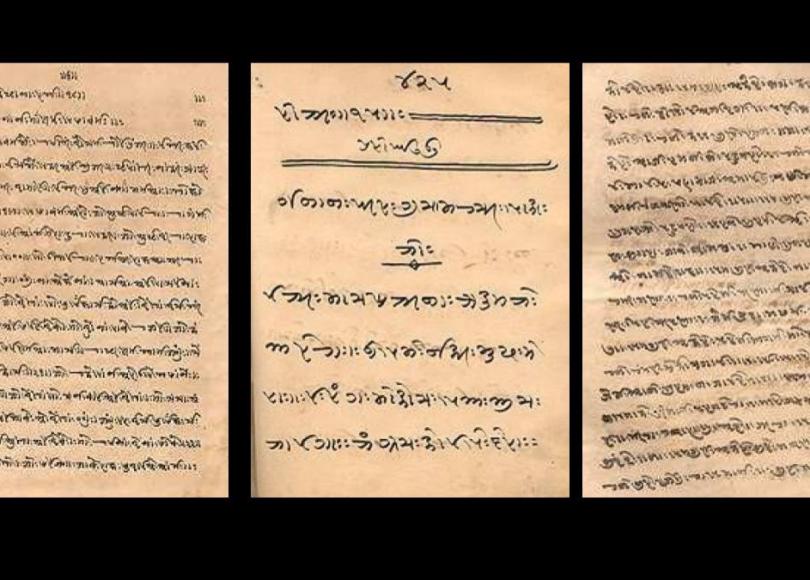

Pir Sadr al-Din Uchch

Pir Sadr al-Din’s mausoleum in Uchchh, India. Source: Ismaili Gnosis

Pandiyat-i javanmardi

As a result of dissension in the community upon the appointment of Pir Taj al-Din, Imams did not appoint Pirs after his death. Instead, a book – Pandiyat-i javanmardi (‘Counsels of Chivalry‘) – containing the guidance of Imam Mustansir billah II (d.1480) was sent. This book came to occupy the twenty-sixth place in the traditional list of Pirs. The Pandiyat also found its way to remote areas in Hunza, Chitral, and Badakshan.

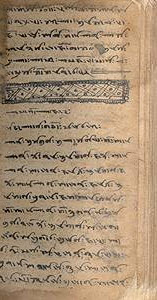

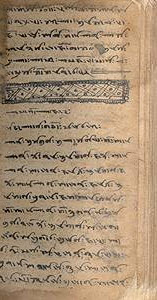

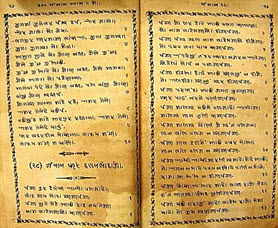

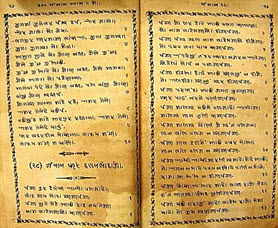

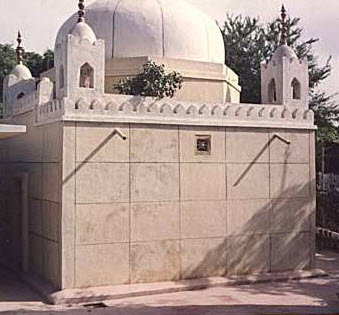

Pandiyat jawanmardi pirs

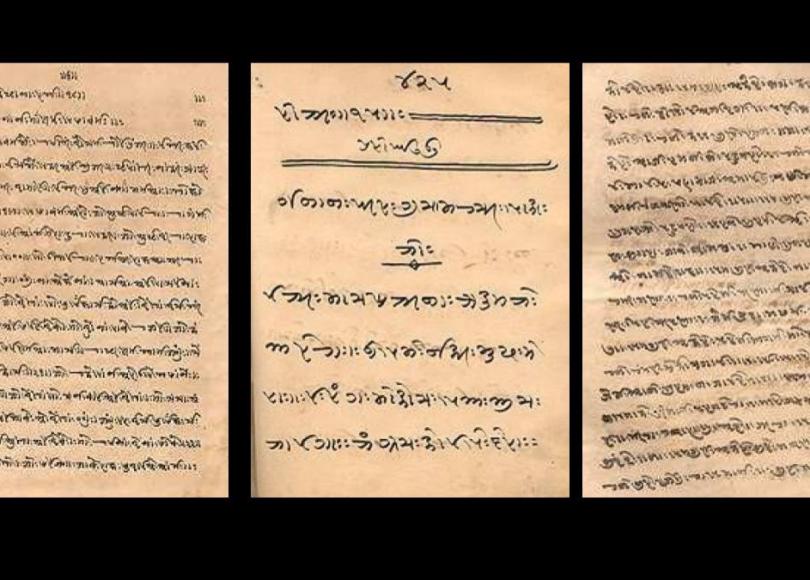

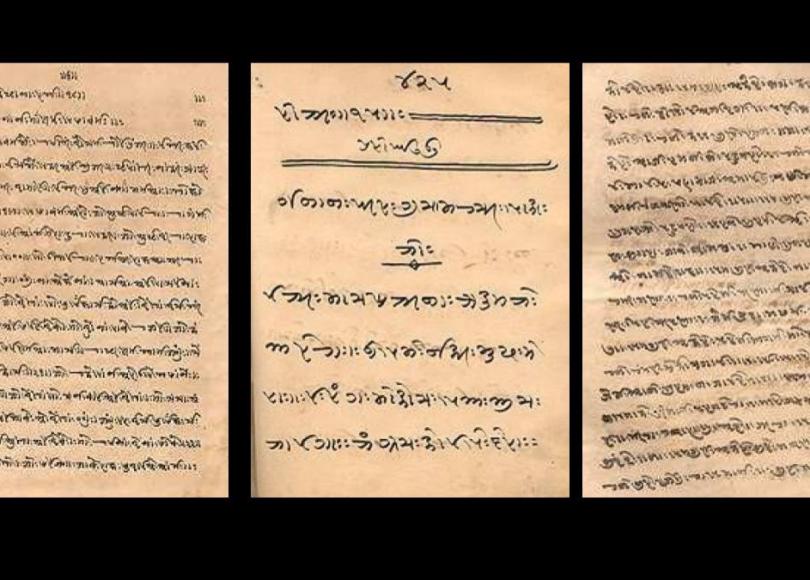

Pandiyat-i Jawanmardi, copied between 1736 and 1879, scribe unknown. Source: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Sayyids

After Pir Taj al-Din, the work of Pirs was continued by a line of Sayyids, generally regarded as the descendants of Pir Hasan Kabir al-Din.

The Arabic word sayyid, meaning ‘lord’ or ‘master,’ refers to a person who possesses dignity or enjoys an exalted position among his people. It is also used as a title for Sufi masters and notable theologians. (IIS Glossary)

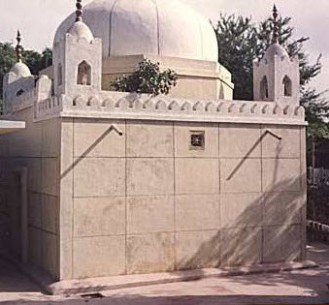

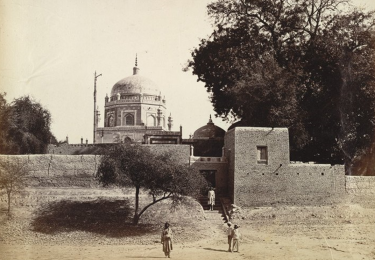

Imam Begum Karachi

Imam Begum’s mausoleum in Karachi, Pakistan. Source: The Institute of Ismaili Studies.

Imam Begum

The last in the line of Sayyids and the only known female composer of Ginans, Imam Begum, who composed ten Ginans, sang her compositions to the accompaniment of the fiddle (sarangi).

Asani notes that the singing of Ginans in unison of the entire congregation “can also be very powerful in its emotional and sensual impact. Even those who may not fully understand the meanings and significance of the words they sing may experience an emotion difficult to describe but which sometimes physically manifests itself through moist eyes or tears” (Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 41).

Sources:

Ali S. Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment, The Ismaili Devotional Literature of South Asia, I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., London, 2002

Azim Nanji, The Nizari Isma’ili Tradition in the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, Caravan Books, New York, 1978

Ginans: A Tradition of Religious Poetry, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

/nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/08/03/pirs-composed-ginans-to-teach-the-ismaili-interpretation-of-islam/

Posted by Nimira Dewji

Ginan bolore nit nure bharea;

evo haide tamare harakh na maeji.

Recite continually the Ginans which are filled with light;

boundless will be the joy in your heart. (tr. Ali Asani). Listen

Ginans are a vast collection comprising several hundred poetic compositions which have been a central part of the religious life of the Nizari Ismaili community of the Indian subcontinent that today resides in many countries around the world. Derived from the Sanskrit gyan, meaning contemplative knowledge, Ginans refer to the poetic compositions authored by Ismaili Pirs, who came to the Indian subcontinent in the eleventh century to teach the Ismaili interpretation of Islam. The literature is also shared by the Imamshahi community in Gujarat, who are believed to have split off from the Nizari Ismailis in the sixteenth century (IIS)

At the time, the field of devotional poetry was flourishing, with figures such as Narasimha Maeta (15th century), Mirabai (1498-1557), Narhari (17th century), Kabir (1440-1518), Guru Nanak (1469-1539), among others. A tradition of mystical poetry was also developing among the Sufis in the subcontinent. The Pirs used the subcontinent’s many languages, folk songs, myths, and traditional music to articulate its core concepts” (Asani, A Modern History of the Ismailis p 96). Compositions were also influenced by the various communities’ needs to assimilate the practices of the dominant local populace in order to avoid persecution.

The form of Nizari Ismail tradition in the subcontinent came to be known as sat panth (‘true path’). The term panth, “an Indic term meaning path, doctrine or sect, is popularly used in the names of groups that crystallized around the different religious personalities of medieval India. For example, followers of the poet Dadu call their movement Dadupanth while those of Kabir use the term Kabirpanth. The term satpanth used by the Ismaili pirs echoes the Qur’anic concept of sirat al-mustaqim (the right path).

Through the medium of Ginans, the Pirs provided guidance on a variety of doctrinal, ethical, and mystical themes for the community while also serving to explain the inner meaning (batin) of the Qur’an to the external (zahir) aspects. The Ginan literature “came to be perceived within the community as a kind of commentary on the Qur’an. Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah explained “In the ginans which Pir Sadardin has composed for you, he has explained the gist of the Qur’an in the language of Hindustan” (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 30).

“According to Paul Walker, the Ismailis have:

tolerated a surprising intellectual flexibility and leeway. That in turn has allowed men of various philosophical temperaments to enter into and promote with enthusiasm this particular kind of Islam… This fact may explain why the Ismaili movement attracted a number of brilliant and creative thinkers and also why others of equal brilliance seem to lean in their direction.”

Cited in Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 7

Language of Ginans

Ginans were composed in Punjabi, Multani (Saraiki), Sindhi, Kachhi, Hindustani/ Hindi, and Gujarati. Compositions were also influenced by the various communities’ needs to assimilate the practices of the dominant local populace in order to avoid persecution.

The specific form of Nizari Ismaili interpretation came to be known by the translation of sirat al-mustaqim, rendered as Satpanth (sat panth, or ‘true path.’)

Themes

The number of verses in Ginans varies from four to ten in the shorter ones to over five-hundred in the longer ones. Generally the shorter versions do not possess titles, therefore, the first verses or refrains serve as titles for identification purpose. Longer Ginans designated as Granths, have titles that may reflect the main theme or message such as the Bujh Niranjan (Knowledge of the Attributeless Deity), a long mystical poem on the spiritual quest of the soul; Soh Kiriya (One-Hundred Obligatory Acts) provides instruction for proper conduct.

Several Ginans are stories or parables that are meant to be interpreted mystically such as Kesri sinh swarup bhulayo (The Lion Forgot his Lion-form), which describes a lion who has forgotten its true identity on account of its upbringing among a flock of sheep. Listen

Many Ginans are supplications (venti) for spiritual enlightenment and vision (darshan, didar) such as Hun re piasi tere darshan ki (I Thirst for a Vision of You), which draws on the symbol of a fish writhing in agony outside its home in water. Listen

Unch thi ayo (Coming From an Exalted Place) is a lament of the soul’s fate in the material world and a plea for the intercession of Prophet Muhammad. Listen

Music

The Ginans were a counterpart to the traditions of the geet, bhajan, and kirtan among the many traditions prevalent in the subcontinent. Like most Indian devotional poetry, Ginans are meant to be sung. Music, therefore, is a vital characteristic of Ginans to invoke specific emotional states such as on special occasions, morning prayers, evening prayers, ghatpat ceremony, or at funerals. Each Ginan is distinguished by its raga, or musical mode, with the name of the composer at the end, a characteristic of North Indian poetry. If a Ginan does not possess a refrain, the first verse is used as refrain, a common practice in the Bhakti and Sant traditions of the subcontinent.

Furthermore, Ginans are meant to be sung from memory and heart rather than from a script in order to eliminate the intermediary (the book) between worshipper and the Divine. To compensate the differences between the poetic and musical metre of a ginan, extra syllables such as ‘re’ and ‘eji’ are often inserted during recitation (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment, p 52, n 50).

Although initially an oral tradition, Ginans were recorded in Khojki, a special script adopted by the Ismaili community of the Indian subcontinent primarily to record the community’s religious literature.

Pir Satgur Nur (d.1094) was the earliest Pir sent to the subcontinent. Nanji states that “Satgur Nur came to Jambu-dvipu from Sahetar-dvipa via the city of Bhildi and proceeded to Patan in Gujarat” (Listen).

The term jambu-dvipa refers to “the land of the jambu tress,” jambu being the name of the species of Jambul (Syzgium cumini of the myrtle family Myrtaceae) or Indian blackberries, dvipa meaning ‘island’ or ‘continent.’ The jambu trees were native to the Indian subcontinent as well as other areas of South Asia and Australia, although subsequently grown in other tropical climates around the world. The trees were considered sacred to Lord Krishna and therefore planted close to Hindu temples.

Pir Satgur Nur was followed by Pir Shams al-Din, who was active in the mid-fourteenth century, mainly in Uchchh and Multan in the province of Sind, and associated with Imam Qasim Shah (r. ca. 1310-1370). Pir Shams is also featured prominently in a number of Sufi traditions.

Satgur Nur pir

Pir Satgur Nur’s Mausoleum. Source: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Garbis

Very popular during the Gujarati culture of western India was the garbi, a folk dance in which individuals move around in a circle and sing to the accompaniment of a rhythmic clap of hands and feet. “the dancers in motion, as well as the songs composed for the occasion are known as garbis” (Nanji, The Nizari Ismaili Tradition p 20)

Pir Shams, who is said to have joined in the dancing of the Hindu festival of Navratri, substituted his own words for theirs, thus teaching them the principles of Ismailism. Pir Shams composed 28 garbis. Listen to the garbi titled Evi garbi sampuran saar.

Pir Sadr al-Din

Pir Shams was succeeded by his son Nasir al-Din and grandson Shihab or Sahib al-Din, both conducting activities in secrecy to avoid persecution. The latter was succeeded by Pir Sadr al-Din, who worked during the time of Imam Islam Shah (r. 1369/70 to 1425/26), and is considered the founder of the Nizari Ismaili Khoja community.

Pir Sadr al-Din played a prominent role in converting many Hindus, giving them the Persian title of khwaja (meaning ‘master’), corresponding to the Hindu title of thakur. He is credited with authoring the largest number of Ginans, and establishing the earliest jamatkhanas in Kotri, Sind in the fifteenth century, with additional ones in Panjab and Kashmir.

Pir Sadr al-Din died between 1369 and 1416; he was succeeded by Pir Hasan Kabir al-Din, (d. ca. 1470) and Pir Taj al-Din (d. end of the 15th century).

Pir Sadr al-Din Uchch

Pir Sadr al-Din’s mausoleum in Uchchh, India. Source: Ismaili Gnosis

Pandiyat-i javanmardi

As a result of dissension in the community upon the appointment of Pir Taj al-Din, Imams did not appoint Pirs after his death. Instead, a book – Pandiyat-i javanmardi (‘Counsels of Chivalry‘) – containing the guidance of Imam Mustansir billah II (d.1480) was sent. This book came to occupy the twenty-sixth place in the traditional list of Pirs. The Pandiyat also found its way to remote areas in Hunza, Chitral, and Badakshan.

Pandiyat jawanmardi pirs

Pandiyat-i Jawanmardi, copied between 1736 and 1879, scribe unknown. Source: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Sayyids

After Pir Taj al-Din, the work of Pirs was continued by a line of Sayyids, generally regarded as the descendants of Pir Hasan Kabir al-Din.

The Arabic word sayyid, meaning ‘lord’ or ‘master,’ refers to a person who possesses dignity or enjoys an exalted position among his people. It is also used as a title for Sufi masters and notable theologians. (IIS Glossary)

Imam Begum Karachi

Imam Begum’s mausoleum in Karachi, Pakistan. Source: The Institute of Ismaili Studies.

Imam Begum

The last in the line of Sayyids and the only known female composer of Ginans, Imam Begum, who composed ten Ginans, sang her compositions to the accompaniment of the fiddle (sarangi).

Asani notes that the singing of Ginans in unison of the entire congregation “can also be very powerful in its emotional and sensual impact. Even those who may not fully understand the meanings and significance of the words they sing may experience an emotion difficult to describe but which sometimes physically manifests itself through moist eyes or tears” (Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 41).

Sources:

Ali S. Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment, The Ismaili Devotional Literature of South Asia, I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., London, 2002

Azim Nanji, The Nizari Isma’ili Tradition in the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, Caravan Books, New York, 1978

Ginans: A Tradition of Religious Poetry, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

/nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/08/03/pirs-composed-ginans-to-teach-the-ismaili-interpretation-of-islam/

Pirs and Sayyids composed ginans within the framework of the society of the time

Posted by Nimira Dewji

Pirs and Sayyids, endowed with spiritual knowledge and experience, composed poetry known as ginans in local Indic languages to be sung according to specific melodies (ragas). Ginans served as literary vehicles for conveying Ismaili doctrines that focus on penetrating to the inner (batin) significance of the Qur’an, into the framework of the societies of the Indian subcontinent. From the Sanskrit gyan, meaning contemplative knowledge, ginans contain emotive knowledge that can transcend the material to connect to the Divine.

“God has treasures beneath His Throne, the keys of which are the Tongues of Poets”

Hadith of Prophet Muhammad

Source: Ali S. Asani, The Ginans: Awakening the Soul Through Wisdom

More on Ginans and Satpanthi Tradition

During the time of the da’wa, Vaishnavism (devotion to Vishnu and his many incarnations, avatars) was one of the dominant Indic streams of religious life in northern India. Pirs introduced their teaching “without totally rejecting the conceptual and even social framework of the society” (Nanji, The Nizari Isam’ili Tradition p 102). Many traditions incorporated indigenous framework into their teachings; for example, “among Sunnis in Bengal, Prophet Muhammad was regarded as the ‘incarnation of God himself.’ He was seen as the last, tenth incarnation of Vishnu, the avatara of Kali-yuga,’ superseding the nine previous incarnations. (Esmail, A Scent of Sandalwood p 29).

Themes

The themes of ginans are diverse ranging from laments of the soul as it proceeds on a spiritual quest, to ethical precepts concerning proper business practice. “One ginan may contain more than one theme that are blended together, however, the corpus comprises some major motifs” (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 45).

1) Integration of Ismaili thought within Vaishnava framework

In this category, ginans explain that “to know the truth, which can be done only through true faith, it is necessary to break once and for all, the relentless chain of karma… which make the wheel of re-birth spin on and on. In this way, the idea of re-birth is invoked not to promote it as an object of belief but to promote commitment to the true faith. The idea of myriad rounds of birth (eight hundred and forty thousand…according to ancient Indian belief), invokes the sense of a human ordeal on a formidable scale. This foreboding is turned into a case for seeking salvation through wholehearted commitment, a surrender of body, mind, and soul to the true faith” (Esmail, A Scent of Sandalwood p 66-67), as taught by Sayyida Imam Begum in verse 2 of the Ginan Aye rahem raheman

Regarding the concept of reincarnation, Esmail notes that the doctrine “is a very old one, as is evident in its presence in cultures across the world from Ancient Greece, Africa, through to India. It is not to be found… in scriptural traditions of Semitic languages. However, it was one of the elements in the extraordinary mix of cultural traditions in the Near East, and was thus one of the contenders in the battle of ideas which shaped the course of the Semitic civilisations. Like the doctrines of the ancient religions of Manicheanism and Zoroastrianism, [religions of ancient Iran] the doctrine of reincarnation was treated by these religious traditions as heretical… in India, it remained all-important, and not only in Hinduism. Popular Islam, including Sufism, retained it, together with a host of other significant, indigenous ideas and symbols….” (Ibid. p 64).

Figures of Hindu mythology such as Harischandra, Draupadi, and the Pandava brothers served as models of proper behaviour and conduct. In order that some of these figures might be of benefit to new converts, they were assimilated into the Ismaili tradition by being re-interpreted with Ismaili perspectives. For example, in the ginan tiled Amar te ayo (The Command has Come), Harischandra is carried over into the ginan tradition, where he becomes the paradigm of the true devotee who is ready to sacrifice everything for his religion (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 45).

The term avatara in Vaishnavism “came to signify the assumptions of different forms, man or animal by God, in which Vishnu came down to earth and lived on it until the purpose for which he had descended into the Universe was fulfilled (Nanji, The Nizari Isam’ili Tradition p 111).

In the ginan Allah ek kasam sabhuka, Pir Hasan Kabirdin explains (v. 16):

Know the Creator [Brahma], Ruler [Vishnu], and the Destroyer of evil [Shiva]

In the present age Lord Vishnu is the Imam.

Those souls that have followed the Farmans,

have reached the abode of paradise.

(tr. Ismaili.net)

One of the functions of avatars “is that they have come, throughout the ages, not only to fight the forces of evil but also to “save” man from the shackles of the cycle of re-birth… Sat Panth is presented as the solution to escape from this cycle and to gain Paradise.” (Nanji, The Nizari Isma’ili Tradition, p 121), as expressed by the Hindu concept of moksha – deliverance and final emancipation from the bondage of existence (Ibid. p 179 n. 89).

The Hindu doctrine had spoken of the coming of the tenth avatar (das avatara) from which the ginans take their name. The ten avatars “were fitted into the framework of a cyclical history on the basis of the Hindu concept of yuga, elaborated into the doctrine of the four yugas or Ages, the four cosmic cycles wherein the Universe was periodically created and destroyed. The four yugas were Krita, Treta, Davapara, and Kali (the present age) considered the age of darkness. The tenth avatar would fight the forces of evil in the Kali Yuga (Ibid. p 111-113). In the ginan titled Pahela karta jugmahe Shahna Pir Sadr al-Din addresses the four yugas, describing that in the present age, Lord Sri Naklank (Hazarat Ali) is seated on the throne. Sayyid Muhammad Shah narrates, in the ginan Sahebji tun more man bhaave :

Lord! I have visited and seen all the four yugas, there is none like you (v 2).

(tr. Kamaluddin, Ginan Central, University of Saskatchewan)

Pir Sadr al-Din warns of the danger of Kalinga in verse 4 of the ginan Firat neja tambal vaajshe:

daeet kaalee(n)gaa naa chhaasatth laakh jodhaa…

The devil’s army has a strength of the magnitude of 6.6 million…

(tr. Ismaili.net)

“Just as in Ismailism, in both its Fatimid and Nizari versions, the forces of evil symbolized by Iblis were set free and disturbed the state of harmony necessitating “the coming of a new Lawgiver to offset the forces of evil, so in Hindu doctrine the various avataras had come to earth to put things right.” The fulfillment of their doctrine of the tenth avatara however, would find its culmination, not in the standard figure of Kalki [Vishnu’s incarnation the destroyer], but as a form of Ali. He was to be the Mahdi who would kill Kalinga, the embodiment of evil, the Iblis of Hindu mythology” (Nanji, The Nizari Isma’ili Tradition, p113).

Pir Imamshah parallels the Four Revealed Books of Islamic Tradition in Moman Chetamni to the Four Vedas, the primary scriptures of Hinduism. All the various chords, merge and centre upon the single figure of the “Imam of the Time,” the tenth avatara.

Tawrat –Prophet Musa

Injil – Gospel of Isa (Jesus)

Qur’an – Prophet Muhammad

Zabur – Book of Dawud (David)

Ginan bolore nit nure bharea;

evo haide tamare harakh na maeji.

Recite continually the Ginans which are filled with light;

boundless will be the joy in your heart.

(tr. Ali Asani). Listen

(Ginan themes to be continued)

Sources:

Ali S. Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment, I.B. Tauris Publishers in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2001

Azim Nanji, The Nizari Isma’ili Tradition in the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, Caravan Books, Delmar, 1978

Aziz Esmail, A Scent of Sandalwood, Curzon Press, Surrey, UK, 2002

Shafique Virani, “Symphony of Gnosis : A Self-Definition of the Ismaili Ginan Tradition,” published in Reason and Inspiration in Islam Edited by Todd Lawson, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2005

/nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/08/17/pirs-and-sayyids-composed-ginans-within-the-framework-of-the-society-of-the-time/

Posted by Nimira Dewji

Pirs and Sayyids, endowed with spiritual knowledge and experience, composed poetry known as ginans in local Indic languages to be sung according to specific melodies (ragas). Ginans served as literary vehicles for conveying Ismaili doctrines that focus on penetrating to the inner (batin) significance of the Qur’an, into the framework of the societies of the Indian subcontinent. From the Sanskrit gyan, meaning contemplative knowledge, ginans contain emotive knowledge that can transcend the material to connect to the Divine.

“God has treasures beneath His Throne, the keys of which are the Tongues of Poets”

Hadith of Prophet Muhammad

Source: Ali S. Asani, The Ginans: Awakening the Soul Through Wisdom

More on Ginans and Satpanthi Tradition

During the time of the da’wa, Vaishnavism (devotion to Vishnu and his many incarnations, avatars) was one of the dominant Indic streams of religious life in northern India. Pirs introduced their teaching “without totally rejecting the conceptual and even social framework of the society” (Nanji, The Nizari Isam’ili Tradition p 102). Many traditions incorporated indigenous framework into their teachings; for example, “among Sunnis in Bengal, Prophet Muhammad was regarded as the ‘incarnation of God himself.’ He was seen as the last, tenth incarnation of Vishnu, the avatara of Kali-yuga,’ superseding the nine previous incarnations. (Esmail, A Scent of Sandalwood p 29).

Themes

The themes of ginans are diverse ranging from laments of the soul as it proceeds on a spiritual quest, to ethical precepts concerning proper business practice. “One ginan may contain more than one theme that are blended together, however, the corpus comprises some major motifs” (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 45).

1) Integration of Ismaili thought within Vaishnava framework

In this category, ginans explain that “to know the truth, which can be done only through true faith, it is necessary to break once and for all, the relentless chain of karma… which make the wheel of re-birth spin on and on. In this way, the idea of re-birth is invoked not to promote it as an object of belief but to promote commitment to the true faith. The idea of myriad rounds of birth (eight hundred and forty thousand…according to ancient Indian belief), invokes the sense of a human ordeal on a formidable scale. This foreboding is turned into a case for seeking salvation through wholehearted commitment, a surrender of body, mind, and soul to the true faith” (Esmail, A Scent of Sandalwood p 66-67), as taught by Sayyida Imam Begum in verse 2 of the Ginan Aye rahem raheman

Regarding the concept of reincarnation, Esmail notes that the doctrine “is a very old one, as is evident in its presence in cultures across the world from Ancient Greece, Africa, through to India. It is not to be found… in scriptural traditions of Semitic languages. However, it was one of the elements in the extraordinary mix of cultural traditions in the Near East, and was thus one of the contenders in the battle of ideas which shaped the course of the Semitic civilisations. Like the doctrines of the ancient religions of Manicheanism and Zoroastrianism, [religions of ancient Iran] the doctrine of reincarnation was treated by these religious traditions as heretical… in India, it remained all-important, and not only in Hinduism. Popular Islam, including Sufism, retained it, together with a host of other significant, indigenous ideas and symbols….” (Ibid. p 64).

Figures of Hindu mythology such as Harischandra, Draupadi, and the Pandava brothers served as models of proper behaviour and conduct. In order that some of these figures might be of benefit to new converts, they were assimilated into the Ismaili tradition by being re-interpreted with Ismaili perspectives. For example, in the ginan tiled Amar te ayo (The Command has Come), Harischandra is carried over into the ginan tradition, where he becomes the paradigm of the true devotee who is ready to sacrifice everything for his religion (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 45).

The term avatara in Vaishnavism “came to signify the assumptions of different forms, man or animal by God, in which Vishnu came down to earth and lived on it until the purpose for which he had descended into the Universe was fulfilled (Nanji, The Nizari Isam’ili Tradition p 111).

In the ginan Allah ek kasam sabhuka, Pir Hasan Kabirdin explains (v. 16):

Know the Creator [Brahma], Ruler [Vishnu], and the Destroyer of evil [Shiva]

In the present age Lord Vishnu is the Imam.

Those souls that have followed the Farmans,

have reached the abode of paradise.

(tr. Ismaili.net)

One of the functions of avatars “is that they have come, throughout the ages, not only to fight the forces of evil but also to “save” man from the shackles of the cycle of re-birth… Sat Panth is presented as the solution to escape from this cycle and to gain Paradise.” (Nanji, The Nizari Isma’ili Tradition, p 121), as expressed by the Hindu concept of moksha – deliverance and final emancipation from the bondage of existence (Ibid. p 179 n. 89).

The Hindu doctrine had spoken of the coming of the tenth avatar (das avatara) from which the ginans take their name. The ten avatars “were fitted into the framework of a cyclical history on the basis of the Hindu concept of yuga, elaborated into the doctrine of the four yugas or Ages, the four cosmic cycles wherein the Universe was periodically created and destroyed. The four yugas were Krita, Treta, Davapara, and Kali (the present age) considered the age of darkness. The tenth avatar would fight the forces of evil in the Kali Yuga (Ibid. p 111-113). In the ginan titled Pahela karta jugmahe Shahna Pir Sadr al-Din addresses the four yugas, describing that in the present age, Lord Sri Naklank (Hazarat Ali) is seated on the throne. Sayyid Muhammad Shah narrates, in the ginan Sahebji tun more man bhaave :

Lord! I have visited and seen all the four yugas, there is none like you (v 2).

(tr. Kamaluddin, Ginan Central, University of Saskatchewan)

Pir Sadr al-Din warns of the danger of Kalinga in verse 4 of the ginan Firat neja tambal vaajshe:

daeet kaalee(n)gaa naa chhaasatth laakh jodhaa…

The devil’s army has a strength of the magnitude of 6.6 million…

(tr. Ismaili.net)

“Just as in Ismailism, in both its Fatimid and Nizari versions, the forces of evil symbolized by Iblis were set free and disturbed the state of harmony necessitating “the coming of a new Lawgiver to offset the forces of evil, so in Hindu doctrine the various avataras had come to earth to put things right.” The fulfillment of their doctrine of the tenth avatara however, would find its culmination, not in the standard figure of Kalki [Vishnu’s incarnation the destroyer], but as a form of Ali. He was to be the Mahdi who would kill Kalinga, the embodiment of evil, the Iblis of Hindu mythology” (Nanji, The Nizari Isma’ili Tradition, p113).

Pir Imamshah parallels the Four Revealed Books of Islamic Tradition in Moman Chetamni to the Four Vedas, the primary scriptures of Hinduism. All the various chords, merge and centre upon the single figure of the “Imam of the Time,” the tenth avatara.

Tawrat –Prophet Musa

Injil – Gospel of Isa (Jesus)

Qur’an – Prophet Muhammad

Zabur – Book of Dawud (David)

Ginan bolore nit nure bharea;

evo haide tamare harakh na maeji.

Recite continually the Ginans which are filled with light;

boundless will be the joy in your heart.

(tr. Ali Asani). Listen

(Ginan themes to be continued)

Sources:

Ali S. Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment, I.B. Tauris Publishers in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2001

Azim Nanji, The Nizari Isma’ili Tradition in the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, Caravan Books, Delmar, 1978

Aziz Esmail, A Scent of Sandalwood, Curzon Press, Surrey, UK, 2002

Shafique Virani, “Symphony of Gnosis : A Self-Definition of the Ismaili Ginan Tradition,” published in Reason and Inspiration in Islam Edited by Todd Lawson, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2005

/nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/08/17/pirs-and-sayyids-composed-ginans-within-the-framework-of-the-society-of-the-time/

Ginan themes include laments of the soul, supplications, and ethics

Posted by Nimira Dewji

“Poetry is the voice of God speaking through the lips of man. If a great painting puts you in direct touch with nature, great poetry puts you in touch with God.”

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III

Source: Ali S Asani, The Ginans: Awakening the Soul Through Wisdom

The term ginan is from the Sanskrit gyan meaning contemplative knowledge, wisdom or gnosis. Nasr translates the term to mean ‘supreme knowledge.’ Ivanow, generally considered the founder of the modern Ismaili studies, said this term ‘is used in the sense of the knowledge, i.e. the real and true, as the Arabic Ismaili term haqa’iq” (Virani, Reason and Inspiration p 504).

The themes of ginans are diverse ranging from laments of the soul as it proceeds on a spiritual quest, to ethical precepts concerning proper business practice. One ginan may contain more than one theme that are blended together, however, the corpus comprises some major motifs (Asani, Ecstatsy and Enlightenment p 45).

1) Integration of Ismaili thought within Vaishnava framework

Pirs and Sayyids, endowed with spiritual knowledge and experience, composed poetry known as ginans in local Indic languages to be sung according to specific melodies (ragas). Ginans served as literary vehicles for conveying Ismaili doctrines that focus on penetrating to the inner (batin) significance of the Qur’an, into the framework of the societies of the Indian subcontinent.

More

2) Destiny of Soul

This category deals with the questioning the soul as it passes through fifty-two stages in the after-life, for example Bavan Ghati (Fifty-two Passes); Brahma Gayantri deals with the creative process from a pre-eternal divine light (an integration of Hindu creation myths into an Islamic context); Naklanki Gita is a mystical cosmogony; and Unchi thi aayo (‘Coming from an Exalted Place’) is a lament of the soul’s fate in the material world and a plea for the intercession of Prophet Muhammad (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 45).

3) Ethics or Morals

Ginans in this category provide instructions for proper conduct of worldy life, for example So Kriya (One-Hundred Obligatory Acts); Bavan Bodh (Fifty-two Advices), and Moman Chetamni (A Warning for the Believers). (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 46).

4) Rituals and Festivals

A number of ginans are recited on specific occasions, for example:

Saat swargna kaim khuloya che dwaar (The Doors of the Seven Heavens Have Swung Open) on the birthday of Prophet Muhammad

Dhan dhan aajno dadalore (Happy and Blessed is This Day) on the birthday of the Imam

Navroz na din sohaman (On This Auspicious Day of Navroz) at the beginning of the Persian New Year

(Ibid. p 28)

5) Mysticism and Spiritual life

“The Ismailis have been notable in Islamic thought for the emphasis they give to the batin, the esoteric aspects of the faith, to complement the zahir, the exoteric or external. Ismaili literature has been concerned throughout its development with the spiritual life of the human soul, especially its search to transcend the shackles of material bondage. The ultimate destiny of the soul is to return to its origin in … God as per the ayat:

“Verily we come from God and to God we return” (Q 2:156).

Such a journey becomes feasible by means of the spiritual relationship that exists between the individual believer and the Imam. As keeper of the mysteries of the batin, the Imam becomes the supreme guide in the spiritual quest (Ibid.). There are compositions that guide an individual’s spiritual progress, composed in the same vein as Sufi manuals such as the granths (long ginans) Bujh Niranjan (Knowledge of the Attributeless Deity ) and Brahma Prakash (Divine Illumination), both of which include descriptions of mystical stages and advice on how to attain them (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 46).

“For the Nizari Ismailis, only the Imam’s spiritual insight and knowledge can provide the faithful with the correct interpretation (ta’wil) that penetrates beyond the formal and literal meaning of the divine word embodied in the Qur’an” (Ibid. p 56).

(Further reading: How the Ismaili Imam teaches esoteric interpretation (ta’wil) of the Holy Qur’an at Ismaili Gnosis)

In mystical ginans, the soul is often represented in the feminine mode as a wife anxious for the return of her husband or a bride awaiting her bridegroom. The woman-soul symbol is a conventional feature in most North Indian devotional poetry written in vernacular languages.

Tamaku sadhare sohodin (The Day that You Left)

Beloved, it has been long since the day you left

(and) anxiously I wait for you.

My merciful lord and kindly master,

O my beloved, how will I spend these days without you?”(Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 57)

It is not uncommon to find ginans using Indic terms for husband or lord (nar, nath, swami) in reference to the Imam. The idea of servitude is also expressed by representing the soul as the servant is slave of the lord. A popular ginan Darshan diyo mora naath (‘Grant me Your Vision, my Lord’), composed by the female saint Imam-Begum, is based entirely on this theme, with the supplicating servant craving didar/darshan (vision) of the Lord” (Ibid. p 58).

Like the sant and Sufi poetry, the ginans draw on a host of symbols taken from the world of nature, agriculture or folk culture to garb their message with a material form e.g. Hun re piasi tere darshan ki (‘I Thirst for a Vision of You’) the symbol of the fish writhing in agony outside its home in water, is used to underline the importance of love, symbolised by water, as the emotive principle of existence (Ibid. p 47). The ginan Kesri sinh swarup bhulayo (The Lion Forgot his Lion-form), describes a lion who has forgotten its true identity on account of its upbringing among a flock of sheep.

6) Supplications (Ventis)

“That Day will faces be bright, looking toward their Lord” (Q 75:22-23)

Ginans in this category are mainly supplications for spiritual enlightenment and vision (darshan or didar), the inner, mystical vision of the Imam’s spiritual light (nur). The concept of nur “constitutes a central motif in the ginans where, in fact, it stood as the primal cause out of which other creations came into being. Pir Shams, in his garbi tith athami avea gamna lok (On the 8th day [of the month] the villagers came and all are looking in amazement), explains Panjtan Pak having been created from Light:

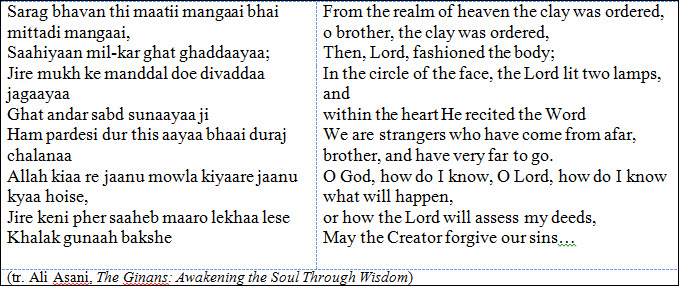

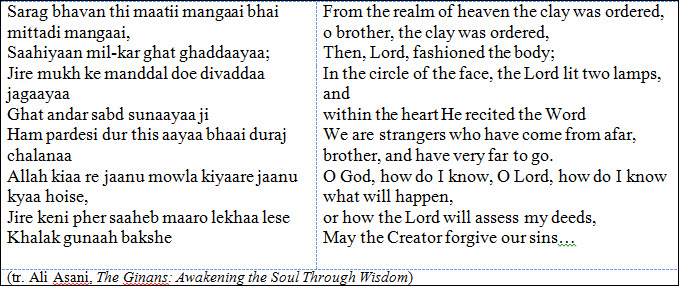

In the ginan sarag bhavan thi maati mangaai Pir Fazal Shah alludes to the popular story of the creation of Adam from clay:

The face was moulded into a circle in which two lamps (eyes) were lit. In the human heart, He recited the Word (sabd). Hence we are connected through our hearts to God through the word – naam, shabd, the ism-e azam. This ginan reminds of our origin with God, and that we are strangers (pardesi) in this world on a long journey back to Him.

Seyyid Imam Shah, in verse 5 of his composition Hetesun milo mara munivaro, says:

Worship with such awareness that the Lord sits manifest in the heart.

(tr. M. and Z. Kamaluddin, Ginan Central, University of Saskatchewan)

In his granth titled Saloko Moto, Pir Shams explains, in the first verse:

Worship the Lord in the heart, and in the heart is the abode of the Lord. In your heart the Lord resides, and in the heart He bestows His Vision.

Photo: AKDN

“As the poet Rumi has written: “The light that lights the eye is also the light of the heart… but the light that lights the heart is the Light of God.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam

Speech

Sources:

Ali S. Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2002

Azim Nanji, The Nizari Isma’ili Tradition in the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, Caravan Books, New York, 1978

Shafiqu N. Virani, “Symphony of Gnosis“, in Reason and Inspiration in Islam Edited by Todd Lawson, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2005

Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Intellect and Intuition: Their Relationship from the Islamic Perspective

Share this:

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/08/21/ginan-themes-include-laments-of-the-soul-supplications-and-ethics/

Posted by Nimira Dewji

“Poetry is the voice of God speaking through the lips of man. If a great painting puts you in direct touch with nature, great poetry puts you in touch with God.”

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III

Source: Ali S Asani, The Ginans: Awakening the Soul Through Wisdom

The term ginan is from the Sanskrit gyan meaning contemplative knowledge, wisdom or gnosis. Nasr translates the term to mean ‘supreme knowledge.’ Ivanow, generally considered the founder of the modern Ismaili studies, said this term ‘is used in the sense of the knowledge, i.e. the real and true, as the Arabic Ismaili term haqa’iq” (Virani, Reason and Inspiration p 504).

The themes of ginans are diverse ranging from laments of the soul as it proceeds on a spiritual quest, to ethical precepts concerning proper business practice. One ginan may contain more than one theme that are blended together, however, the corpus comprises some major motifs (Asani, Ecstatsy and Enlightenment p 45).

1) Integration of Ismaili thought within Vaishnava framework

Pirs and Sayyids, endowed with spiritual knowledge and experience, composed poetry known as ginans in local Indic languages to be sung according to specific melodies (ragas). Ginans served as literary vehicles for conveying Ismaili doctrines that focus on penetrating to the inner (batin) significance of the Qur’an, into the framework of the societies of the Indian subcontinent.

More

2) Destiny of Soul

This category deals with the questioning the soul as it passes through fifty-two stages in the after-life, for example Bavan Ghati (Fifty-two Passes); Brahma Gayantri deals with the creative process from a pre-eternal divine light (an integration of Hindu creation myths into an Islamic context); Naklanki Gita is a mystical cosmogony; and Unchi thi aayo (‘Coming from an Exalted Place’) is a lament of the soul’s fate in the material world and a plea for the intercession of Prophet Muhammad (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 45).

3) Ethics or Morals

Ginans in this category provide instructions for proper conduct of worldy life, for example So Kriya (One-Hundred Obligatory Acts); Bavan Bodh (Fifty-two Advices), and Moman Chetamni (A Warning for the Believers). (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 46).

4) Rituals and Festivals

A number of ginans are recited on specific occasions, for example:

Saat swargna kaim khuloya che dwaar (The Doors of the Seven Heavens Have Swung Open) on the birthday of Prophet Muhammad

Dhan dhan aajno dadalore (Happy and Blessed is This Day) on the birthday of the Imam

Navroz na din sohaman (On This Auspicious Day of Navroz) at the beginning of the Persian New Year

(Ibid. p 28)

5) Mysticism and Spiritual life

“The Ismailis have been notable in Islamic thought for the emphasis they give to the batin, the esoteric aspects of the faith, to complement the zahir, the exoteric or external. Ismaili literature has been concerned throughout its development with the spiritual life of the human soul, especially its search to transcend the shackles of material bondage. The ultimate destiny of the soul is to return to its origin in … God as per the ayat:

“Verily we come from God and to God we return” (Q 2:156).

Such a journey becomes feasible by means of the spiritual relationship that exists between the individual believer and the Imam. As keeper of the mysteries of the batin, the Imam becomes the supreme guide in the spiritual quest (Ibid.). There are compositions that guide an individual’s spiritual progress, composed in the same vein as Sufi manuals such as the granths (long ginans) Bujh Niranjan (Knowledge of the Attributeless Deity ) and Brahma Prakash (Divine Illumination), both of which include descriptions of mystical stages and advice on how to attain them (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 46).

“For the Nizari Ismailis, only the Imam’s spiritual insight and knowledge can provide the faithful with the correct interpretation (ta’wil) that penetrates beyond the formal and literal meaning of the divine word embodied in the Qur’an” (Ibid. p 56).

(Further reading: How the Ismaili Imam teaches esoteric interpretation (ta’wil) of the Holy Qur’an at Ismaili Gnosis)

In mystical ginans, the soul is often represented in the feminine mode as a wife anxious for the return of her husband or a bride awaiting her bridegroom. The woman-soul symbol is a conventional feature in most North Indian devotional poetry written in vernacular languages.

Tamaku sadhare sohodin (The Day that You Left)

Beloved, it has been long since the day you left

(and) anxiously I wait for you.

My merciful lord and kindly master,

O my beloved, how will I spend these days without you?”(Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 57)

It is not uncommon to find ginans using Indic terms for husband or lord (nar, nath, swami) in reference to the Imam. The idea of servitude is also expressed by representing the soul as the servant is slave of the lord. A popular ginan Darshan diyo mora naath (‘Grant me Your Vision, my Lord’), composed by the female saint Imam-Begum, is based entirely on this theme, with the supplicating servant craving didar/darshan (vision) of the Lord” (Ibid. p 58).

Like the sant and Sufi poetry, the ginans draw on a host of symbols taken from the world of nature, agriculture or folk culture to garb their message with a material form e.g. Hun re piasi tere darshan ki (‘I Thirst for a Vision of You’) the symbol of the fish writhing in agony outside its home in water, is used to underline the importance of love, symbolised by water, as the emotive principle of existence (Ibid. p 47). The ginan Kesri sinh swarup bhulayo (The Lion Forgot his Lion-form), describes a lion who has forgotten its true identity on account of its upbringing among a flock of sheep.

6) Supplications (Ventis)

“That Day will faces be bright, looking toward their Lord” (Q 75:22-23)

Ginans in this category are mainly supplications for spiritual enlightenment and vision (darshan or didar), the inner, mystical vision of the Imam’s spiritual light (nur). The concept of nur “constitutes a central motif in the ginans where, in fact, it stood as the primal cause out of which other creations came into being. Pir Shams, in his garbi tith athami avea gamna lok (On the 8th day [of the month] the villagers came and all are looking in amazement), explains Panjtan Pak having been created from Light:

In the ginan sarag bhavan thi maati mangaai Pir Fazal Shah alludes to the popular story of the creation of Adam from clay:

The face was moulded into a circle in which two lamps (eyes) were lit. In the human heart, He recited the Word (sabd). Hence we are connected through our hearts to God through the word – naam, shabd, the ism-e azam. This ginan reminds of our origin with God, and that we are strangers (pardesi) in this world on a long journey back to Him.

Seyyid Imam Shah, in verse 5 of his composition Hetesun milo mara munivaro, says:

Worship with such awareness that the Lord sits manifest in the heart.

(tr. M. and Z. Kamaluddin, Ginan Central, University of Saskatchewan)

In his granth titled Saloko Moto, Pir Shams explains, in the first verse:

Worship the Lord in the heart, and in the heart is the abode of the Lord. In your heart the Lord resides, and in the heart He bestows His Vision.

Photo: AKDN

“As the poet Rumi has written: “The light that lights the eye is also the light of the heart… but the light that lights the heart is the Light of God.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam

Speech

Sources:

Ali S. Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2002

Azim Nanji, The Nizari Isma’ili Tradition in the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, Caravan Books, New York, 1978

Shafiqu N. Virani, “Symphony of Gnosis“, in Reason and Inspiration in Islam Edited by Todd Lawson, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2005

Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Intellect and Intuition: Their Relationship from the Islamic Perspective

Share this:

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/08/21/ginan-themes-include-laments-of-the-soul-supplications-and-ethics/

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah: ‘In the ginans which Pir Sadardin has composed for you, he has explained the gist of the Qur’an in the language of Hindustan’

Ginans are a vast collection consisting of several hundred compositions which have been a central part of the religious life of the Nizari Ismaili community of the Indian subcontinent that today resides in many countries around the world. Derived from the Sanskrit jnana, meaning contemplative knowledge, Ginans refer to the poetic compositions authored by Ismaili Pirs, who came to the Indian subcontinent as early as the eleventh century to teach the message of Revelation to non-Arabic speaking people.

The Pirs, sent by Imams residing in Persia, “were no ordinary missionaries …they were spiritually enlightened individuals whose religious and spiritual authority the Isma’ili imams had formally endorsed by bestowing on them the title of pir” (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 84). One could not become a Pir through inheritance unless he had been so designated by the Imam of the Time. Hence, the Pirs became tangible symbols of the Imam’s authority in South Asia. (Asani, Medieval Ismaili History and Thought p 267-8). “They were second only to the Imam himself in the Ismaili hierarchy” (Virani, “Symphony of Ginans,” Reason and Inspiration in Islam p 502-3). The literature is also shared by the Imamshahi community in Gujarat, who are believed to have split off from the Nizari Ismailis in the sixteenth century (IIS).

At the time, the field of devotional poetry was flourishing in the subcontinent, with figures such as Narasimha Maeta (15th century), Mirabai (1498-1557), Narhari (17th century), Kabir (1440-1518), Guru Nanak (1469-1539), among others. A tradition of mystical poetry was also developing among the Sufis in the subcontinent. The Pirs used the subcontinent’s many languages, folk songs, myths, and traditional music to articulate its core concepts” (Asani, A Modern History of the Ismailis p 96). Compositions were also influenced by the various communities’ needs to assimilate the practices of the dominant local populace in order to avoid persecution.

The form of Nizari Ismail tradition in the subcontinent came to be known as sat panth (‘true path’). The term panth, “an Indic term meaning path, doctrine or sect, is popularly used in the names of groups that crystallized around the different religious personalities of medieval India. For example, followers of the poet Dadu call their movement Dadupanth while those of Kabir use the term Kabirpanth. The term satpanth used by the Ismaili Pirs echoes the Qur’anic concept of sirat al-mustaqim (the right path).

Common to all these traditions was the use of Indian vernaculars of the respective local regions enabling the composers to use local music styles to sing their poetry to facilitate the journey to spiritual ecstasy. Compositions were also influenced by the various communities’ needs to assimilate the practices of the dominant local community in order to avoid persecution. About thirty da’is composed ginans in several languages over a period of six centuries.

Through the poetic medium of ginans, Pirs explained the Qur’an to the converts. In his pronouncement, Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah guided the community in this issue: ‘In the ginans which Pir Sadardin has composed for you, he has explained the gist of the Qur’an in the language of Hindustan.’ (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 30).

A composition titled Moman Chetamni (‘A Warning for the Believers’) clarifies the Qur’an as the source of Satpanth :

Eji Ali Nabi thi je satpanth chaliaa

Tene sreviay gupt aapar

Atharvedi aa panth kahiae

Te to khojiya kuran minjar Cheto…. (v. 162).

Satpanth began from Ali and Prophet Muhammad;

follow it more discreetly.

this Satpanth is according to Athar Veda (the last Veda [Hindu scriptures])

you can find its proof in the Qur’an.

(Ali Asani, Hymns of Wisdom, McKenna College)

In verse 202 of his granth titled Saloko Moto (also termed Vaek Moto), Pir Shams explains:

Satgur kahere Pir Shams kuran ja bhakhiya,

Ane bhakhiya char ved ja jan;

Te gat gangamanhe besi kari,

Kidhi sachi saankh nirvan re…

Pir Shams has preached the Qur’an

and preached the four Vedas;

among the gat jamat (congregation)

he has narrated the true signs.

(Tr. Ali Asani)

In his composition Sat maarag Shams Pir, verse 5 says:

Gur naache garbi maahe

Te gaae kuran ne re lol

The Pir danced to the garbi and

explained the teachings of the Qur’an.

(tr. M. Kamaluddin, Ginan Central, University of Saskatchewan)

Pir Sadardin, in his composition Aas punee hum Shah dar paaya, says:

Pir Sadardin yaaraa pade re Kuran

Baahaar jaave taaku andar laanaa,

Shah naa sujaano aapnaa pirne pichhaano (v. 6).

Pir Sadardin recites the Qur’an

He brings back into the fold those who leave it.

Know the Imam (in his essence) and recognise your Pir (Guide).

(tr. Ismaili.net).

In another of his composition Aasmani tambal vaajiyaa Pir Sadardin states:

Kal maanhe Muhammad Shaahni vinati; tame bhuli ma jaao ji (v 13)

In the present age Prophet Muhammad pleads: “do not be forgetful.”

Ved Quraan maanhe saakh chhe; teni aavi edhaanni ji (v. 14)

The evidence of the coming of and the function and authority of the Imam is to be found in the holy scriptures and the Holy Qur’an. You have been forewarned about it.

Pir Sadardin boliyaa; tame ginaan vichaaro ji (v. 15)

Pir Sadardin has said: “Reflect upon the ginans.”

(tr. Karim Maherali, Ismailimail)

In verse 2 of the ginan Allah ek kasam sabhu ka, Pir Hasan Kabirdin says:

Nabi Muhammad bujo bhai, to tame paamo Imam

mushrak mun to kaffir kahinye, moman dil qur’an

Brothers, know Prophet Muhammed, then you will attain recognition of the Imam

only a non-believer has polytheistic tendencies in his/her heart

but a momin’s heart is enlightened by Holy Qur’an.

(tr. Ismaiili.net)

This verse resonates in the Qur’an as:

“But it is clear revelations in the hearts of those who have been given knowledge and none deny our revelations save wrong-doers” (29:49).

In the ginan Tun hi gur tun hi nar, Pir Sadardin worries:

Ek fikar munivar tamaari chhe amne

maannas rupe saaheb jaanno ho bhaai ji (verse 4).

O true believers! We have one concern about you and that is that you might confuse Imam in his physical form as an ordinary man.

(tr. M & Z Kamaluddin, Ginan Central, University of Saskatchewan)

Sources:

Shafique N. Virani, “Symphony of Gnosis,” Reason and Inspiration in Islam Ed. Todd Lawson, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2005 (p 502-521)

Ali Asani, Hymns of Wisdom, Claremont McKenna College (1:09:46)

Ali Asani, The Ginans – Awakening the Soul Through Wisdom (1:14:14)

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/09/09/imam-sultan-muhammad-shah-in-the-ginans-which-pir-sadardin-has-composed-for-you-he-has-explained-the-gist-of-the-quran-in-the-language-of-hindustan/

Ginans are a vast collection consisting of several hundred compositions which have been a central part of the religious life of the Nizari Ismaili community of the Indian subcontinent that today resides in many countries around the world. Derived from the Sanskrit jnana, meaning contemplative knowledge, Ginans refer to the poetic compositions authored by Ismaili Pirs, who came to the Indian subcontinent as early as the eleventh century to teach the message of Revelation to non-Arabic speaking people.

The Pirs, sent by Imams residing in Persia, “were no ordinary missionaries …they were spiritually enlightened individuals whose religious and spiritual authority the Isma’ili imams had formally endorsed by bestowing on them the title of pir” (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 84). One could not become a Pir through inheritance unless he had been so designated by the Imam of the Time. Hence, the Pirs became tangible symbols of the Imam’s authority in South Asia. (Asani, Medieval Ismaili History and Thought p 267-8). “They were second only to the Imam himself in the Ismaili hierarchy” (Virani, “Symphony of Ginans,” Reason and Inspiration in Islam p 502-3). The literature is also shared by the Imamshahi community in Gujarat, who are believed to have split off from the Nizari Ismailis in the sixteenth century (IIS).

At the time, the field of devotional poetry was flourishing in the subcontinent, with figures such as Narasimha Maeta (15th century), Mirabai (1498-1557), Narhari (17th century), Kabir (1440-1518), Guru Nanak (1469-1539), among others. A tradition of mystical poetry was also developing among the Sufis in the subcontinent. The Pirs used the subcontinent’s many languages, folk songs, myths, and traditional music to articulate its core concepts” (Asani, A Modern History of the Ismailis p 96). Compositions were also influenced by the various communities’ needs to assimilate the practices of the dominant local populace in order to avoid persecution.

The form of Nizari Ismail tradition in the subcontinent came to be known as sat panth (‘true path’). The term panth, “an Indic term meaning path, doctrine or sect, is popularly used in the names of groups that crystallized around the different religious personalities of medieval India. For example, followers of the poet Dadu call their movement Dadupanth while those of Kabir use the term Kabirpanth. The term satpanth used by the Ismaili Pirs echoes the Qur’anic concept of sirat al-mustaqim (the right path).

Common to all these traditions was the use of Indian vernaculars of the respective local regions enabling the composers to use local music styles to sing their poetry to facilitate the journey to spiritual ecstasy. Compositions were also influenced by the various communities’ needs to assimilate the practices of the dominant local community in order to avoid persecution. About thirty da’is composed ginans in several languages over a period of six centuries.

Through the poetic medium of ginans, Pirs explained the Qur’an to the converts. In his pronouncement, Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah guided the community in this issue: ‘In the ginans which Pir Sadardin has composed for you, he has explained the gist of the Qur’an in the language of Hindustan.’ (Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment p 30).

A composition titled Moman Chetamni (‘A Warning for the Believers’) clarifies the Qur’an as the source of Satpanth :

Eji Ali Nabi thi je satpanth chaliaa

Tene sreviay gupt aapar

Atharvedi aa panth kahiae

Te to khojiya kuran minjar Cheto…. (v. 162).

Satpanth began from Ali and Prophet Muhammad;

follow it more discreetly.

this Satpanth is according to Athar Veda (the last Veda [Hindu scriptures])

you can find its proof in the Qur’an.

(Ali Asani, Hymns of Wisdom, McKenna College)

In verse 202 of his granth titled Saloko Moto (also termed Vaek Moto), Pir Shams explains:

Satgur kahere Pir Shams kuran ja bhakhiya,

Ane bhakhiya char ved ja jan;

Te gat gangamanhe besi kari,

Kidhi sachi saankh nirvan re…

Pir Shams has preached the Qur’an

and preached the four Vedas;

among the gat jamat (congregation)

he has narrated the true signs.

(Tr. Ali Asani)

In his composition Sat maarag Shams Pir, verse 5 says:

Gur naache garbi maahe

Te gaae kuran ne re lol

The Pir danced to the garbi and

explained the teachings of the Qur’an.

(tr. M. Kamaluddin, Ginan Central, University of Saskatchewan)

Pir Sadardin, in his composition Aas punee hum Shah dar paaya, says:

Pir Sadardin yaaraa pade re Kuran

Baahaar jaave taaku andar laanaa,

Shah naa sujaano aapnaa pirne pichhaano (v. 6).

Pir Sadardin recites the Qur’an

He brings back into the fold those who leave it.

Know the Imam (in his essence) and recognise your Pir (Guide).

(tr. Ismaili.net).

In another of his composition Aasmani tambal vaajiyaa Pir Sadardin states:

Kal maanhe Muhammad Shaahni vinati; tame bhuli ma jaao ji (v 13)

In the present age Prophet Muhammad pleads: “do not be forgetful.”

Ved Quraan maanhe saakh chhe; teni aavi edhaanni ji (v. 14)

The evidence of the coming of and the function and authority of the Imam is to be found in the holy scriptures and the Holy Qur’an. You have been forewarned about it.

Pir Sadardin boliyaa; tame ginaan vichaaro ji (v. 15)

Pir Sadardin has said: “Reflect upon the ginans.”

(tr. Karim Maherali, Ismailimail)

In verse 2 of the ginan Allah ek kasam sabhu ka, Pir Hasan Kabirdin says:

Nabi Muhammad bujo bhai, to tame paamo Imam

mushrak mun to kaffir kahinye, moman dil qur’an

Brothers, know Prophet Muhammed, then you will attain recognition of the Imam

only a non-believer has polytheistic tendencies in his/her heart

but a momin’s heart is enlightened by Holy Qur’an.

(tr. Ismaiili.net)

This verse resonates in the Qur’an as:

“But it is clear revelations in the hearts of those who have been given knowledge and none deny our revelations save wrong-doers” (29:49).

In the ginan Tun hi gur tun hi nar, Pir Sadardin worries:

Ek fikar munivar tamaari chhe amne

maannas rupe saaheb jaanno ho bhaai ji (verse 4).

O true believers! We have one concern about you and that is that you might confuse Imam in his physical form as an ordinary man.

(tr. M & Z Kamaluddin, Ginan Central, University of Saskatchewan)

Sources:

Shafique N. Virani, “Symphony of Gnosis,” Reason and Inspiration in Islam Ed. Todd Lawson, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2005 (p 502-521)

Ali Asani, Hymns of Wisdom, Claremont McKenna College (1:09:46)

Ali Asani, The Ginans – Awakening the Soul Through Wisdom (1:14:14)

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/09/09/imam-sultan-muhammad-shah-in-the-ginans-which-pir-sadardin-has-composed-for-you-he-has-explained-the-gist-of-the-quran-in-the-language-of-hindustan/

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah: “Poetry is the voice of God speaking through the lips of man”

Posted by Nimira Dewji

Ginans are a vast collection comprising several hundred poetic compositions which have been a central part of the religious life of the Nizari Ismaili community of the Indian subcontinent that today resides in many countries around the world. Derived from the Sanskrit gyan, meaning contemplative knowledge, ginans refer to the poetic compositions authored by Ismaili Pirs, who came to the Indian subcontinent in the eleventh century to teach the message of Revelation to non-Arabic speaking peoples.

Like most Indian devotional poetry, ginans are meant to be sung. Music, therefore, is a vital characteristic of ginans to invoke specific emotional states such as on special occasions, morning prayers, evening prayers, ghatpat ceremony, or at funerals. Each ginan is distinguished by its raga, or musical mode, with the name of the composer at the end, a characteristic of North Indian poetry. Literature in the local languages were instrumental in explaining Islamic concepts and the Ismaili interpretation in a manner that would be accessible to the local culture environment.

A distinctive aspect of Ismaili thought “is the belief that the Divine or the Truth (haqiqa) can only be accessed by penetrating the esoteric (batin) dimension concealed by the physical or exoteric (zahir) realm. … In this regard, they perceive their imams to be holders of authoritative knowledge (ilm) of both the exoteric and esoteric truth found in the Qur’an, sharia and legal rulings, [mystical] knowledge, and gnosis (ma’rifa). The Imams provide authoritative instruction (ta’lim) and the esoteric interpretation (ta’wil) of divine revelation by decoding the revelatory discourse (tanzil) brought by the prophets” (Asani, Nizari Ismaili Engagements with the Qur’an p 40-42).

“The belief in a pre-eternal or gnostic wisdom in the possession of the Prophet’s family (ahl al-bayt) has been a characteristic feature of Shi’i Islam since the earliest days. The Ismaili branch of Shi’ism, in particular, was well-known for its proselytising activities (da’wa) and call to recognise the inherited knowledge (ilm) of its line of Imams” (Ibid).

“Among the da’is dispatched were several figures whose names appear in the traditional list of pirs, or chief representatives of the Imams” (Asani, Ecstatsy and Enlightenment p 45). They were second only to the Imam himself in the Ismaili hierarchy” (Virani, “Symphony of Ginans,” Reason and Inspiration in Islam p 502-503).

The themes of ginans are diverse ranging from laments of the soul as it proceeds on a spiritual quest, to ethical precepts concerning proper business practice. One ginan may contain more than one theme that are blended together, to convey teachings of the Qur’an.

One of the Qur’anic injunctions is the constant remembrance of the Lord:

“And remember the Name of your Lord and devote yourself to Him with [complete] devotion”⁣

(Qur’an 73:8)⁣.

“The men of intellect are those who remember Allah standing, sitting and reclining.”

(Qur’an 3:190-191)

Pirs and their descendants Sayyids, conveyed this message through their poetic compositions:

Pir Shams narrates, in his ginan Kesri sinh swaroop bhoolaayo, about a lion who was raised among goats and forgot his lionish form. Pir reminds believers to not forget life’s purpose in the delusionary world, and to constantly remember the Lord:

Bharam sab chhodi bhai Ali Ali karnaa,

Hae bhi Ali ne hoeshe bhi Ali

Esaa vachan tame dil maahe dharnaa

Forsaking all delusions, brother, keep reciting the name of Ali,

‘Ali is now and Ali will [always] be’

are the words you should take to heart.

(tr. Ali Asani)

Pir Shams also guides in his composition titled Brahm Prakash, verse 2:

Sat shabd kaa karo veechaaraa

Pir Shah kaho jee vaaram vaaraa

Reflect (meditate) upon the True Word

and say Pir Shah (name of the Lord), repeat again and again.

(tr Ismaili.net)

Pir Hasan Kabirdin:

Khaadiya padiyaa letiyaa bethiyaa mede bhaaive,

hardam saami raajo sambhaariya. (v 1).

Standing or lying down, reclining or sitting,

remember the Lord at all times.

(tr. M & Z Kamaluddin, Ginan Central, University of Saskatchewan)

In his composition Dur desh thi aayo vanjzaaro, he reminds of the soul’s journey from a faraway land, and says in verse 2:

Soote bethe bhaai raah chalantaa

naam Saahebji ko lijiye.

Sleeping, sitting or walking along the way,

take the name of the Lord.

(tr. M & Z Kamaluddin, Ginan Central, University of Saskatchewan)

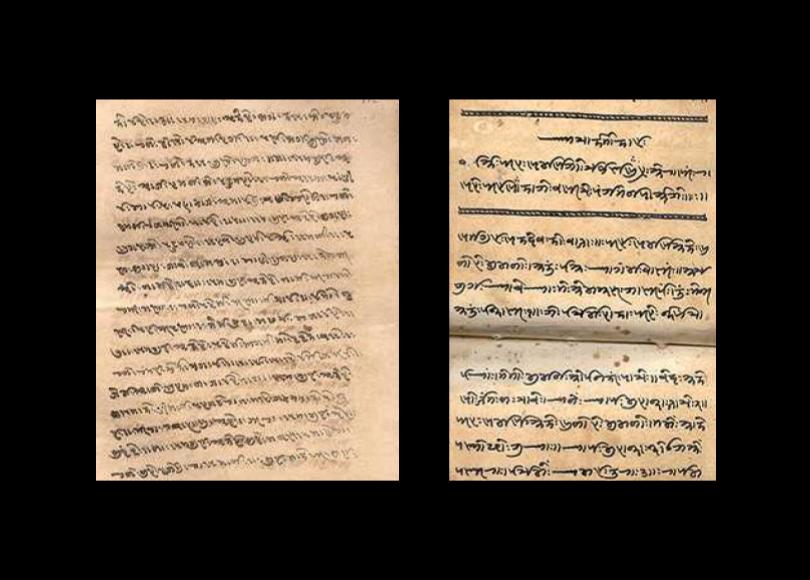

Dur deshi thi aayo vanazro manuscript.

Source: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Pir Sadardin, in his composition Kahore pandito, guides:

Ali bolo Ali bolo munivar jan

Ali ke charan chit laavo ek man.

Remember the name of Ali again and again

concentrate and bring your heart at the feet of Ali.

Ek shabd thi bhavsaagar tariye

te japtaa aalas nav kariye.

The one Word which can take you across the ocean of life

do not be slothful in remembering it.

(tr. M & Z Kamaluddin, Ginan Central, University of Saskatchewan)

Sayyid Imam Shah also states, in his composition Hetesun milo maaraa munivaro, verse 2:

Paak to Saahebji nu naam chhe,

tene jampiye saas usaas…

The name of the Imam is holy

remember it with every breathe….

(tr. M & Z Kamaluddin, Ginan Central, University of Saskatchewan)

Sayyida Imam Begum explains in verse 6 of her composition Tum chet man meraa:

Hardam zikar karnaa

surat nirat un par dharanaa

Pir Shah ka jap japnaa aath jaam lailo nihaar

Keep on remembering His name all the time

concentrate your thoughts on it

continuously repeat the name of Pir Shah day and night.

(tr. M & Z Kamaluddin, Ginan Central, University of Saskatchewan)

Imam Begum Ginans

Mausoleum of Imam Begum in Karachi. Source: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

“Poetry is the voice of God speaking through the lips of man. If a great painting puts you in direct touch with nature, great poetry puts you in touch with God.”

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III

(Source: Ali S Asani, The Ginans: Awakening the Soul Through Wisdom)

Also see

Pirs composed Ginans to teach the Ismaili interpretation of Islam

Ginan composers were acquainted with an already well-developed set of Ismaili beliefs

Ginan themes include laments of the soul, supplications, and ethics

Pir Shams composed the largest number of the garbi form of ginans

Sources:

Ali Asani, Hymns of Wisdom, Claremont McKenna College (1:09:46)

Ali Asani, The Ginans – Awakening the Soul Through Wisdom (1:14:14)

Ali Asani, “Nizari Ismaili Engagements with the Qur’an: the Khojas of South Asia” published in Communities of the Qur’an, Edited by Emran El-Badawi and Paula Sanders, Oneworld Academic, 2019

Shafique N. Virani, “Symphony of Gnosis,” published in Reason and Inspiration in Islam Ed. Todd Lawson, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2005 (p 502-521)

/nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/09/13/imam-sultan-muhammad-shah-poetry-is-the-voice-of-god-speaking-through-the-lips-of-man-2/

Posted by Nimira Dewji