“Nasir al-Din Tusi”

Dr Sayyad Jalal Badakhchani

This article was originally published in The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. James Fieser, at http://www.utm.edu/research/iep/t/tusi.htm, 2003.

Download PDF version of article (105 KB)

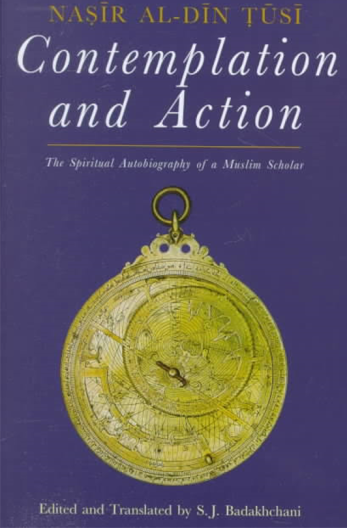

Nasir al-Din Tusi, Muhammad b. Muhammad b. Hasan, by far the most celebrated scholar of the 7th/13th century Islamic lands was born in Tus, in 597/1201 and died in Baghdad on 18 Dhu’l Hijja 672/25 June, 1274. Thomas Aquinas and Roger Bacon were his contemporaries in the West. Very little is known about his childhood and early education, apart from what he writes in his autobiography, Contemplation and Action (Sayr wa suluk).

Tusi’s Early Life

He was apparently born into a Twelver Shi‘i family and lost his father at a young age. Fulfilling the wish of his father, the young Muhammad took learning and scholarship very seriously and travelled far and wide to attend the lectures of renowned scholars and ‘acquire the knowledge which guides people to the happiness of the next world.’ As a young boy, Tusi studied mathematics with Kamal al-Din Hasib about whom we have no authentic knowledge. In Nishapur he met Farid al-Din ‘Attar, the legendary Sufi master who was later killed in the hand of Mongol invaders and attended the lectures of Qutb al-Din Misri and Farid al-Din Damad. In Mosul he studied mathematics and astronomy with Kamal al-Din Yunus (d. 639/1242). Later on he corresponded with Qaysari, the son-in-law of Ibn al-‘Arabi, and it seems that mysticism, as propagated by Sufi masters of his time, was not appealing to his mind and once the occasion was suitable, he composed his own manual of philosophical Sufism in the form of a small booklet entitled The Attributes of the Illustrious (Awsaf al-ashraf).

His ability and talent in learning enabled Tusi to master a number disciplines in a relatively short period. At the time when educational priorities leaned towards the religious sciences, especially in his own family who were associated with the Twelver Shi‘i clergy, Tusi seems to have shown great interest for mathematics, astronomy and the intellectual sciences. At the age of twenty-two or shortly after, Tusi joined the court of Nasir al-Din Muhtashim, the Ismaili governor of Quhistan, Northeast Iran, where he was accepted into the Ismaili community as a novice (mustajib). A sign of close personal relationship with Muhtashim’s family is to be seen in the dedication of a number of his scholarly works such as Akhlaq-i Nasiri and Akhlaq-i Muhtashimi to Nasir al-Din himself and Risala-yi Mu‘iniyya to his son Mu‘in al-Din.

Arrival at Alamut

Around 634/1236, we find Tusi in Alamut, the centre of Nizari Ismaili government. The scholarly achievements of Tusi in the compilation of Akhlaq-i Nasiri in 633/1235, seems to, amongst other factors, have paved the way for this move which was a great honour and opportunity for a scholar of his calibre, especially since Alamut was the seat of the Ismaili imam and housed the most important library in the Ismaili state.

In Alamut, apart from teaching, editing, dictating and compiling scholarly works, Tusi seems to have climbed the ranks of the Ismaili da‘wa ascending to the position of chief missionary (da‘i al-du‘at). Through constant visits with scholars and tireless correspondences, a practice which he developed from a very young age, Tusi kept his contact with the academic world outside Ismaili circles and was addressed as ‘the scholar’ (al-muhaqiq) from a very early period in his life.

The Impact of the Mongol Invasion

The Mongol invasion and the turmoil they caused in the eastern Islamic territories hardly left the life of any of its citizens untouched. The collapse of Ismaili political power and the massacre of the Ismaili population, who were a serious threat to the Mongols, left no choice for Tusi except the exhibition of some sort of affiliation to Twelver Shi‘ism and denouncing his Ismaili allegiances.

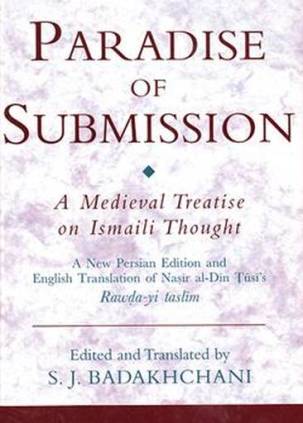

Although under Mongol domination, Tusi’s allegiance to any particular community or persuasion could not have been of any particular importance, the process itself paved the ground for Tusi to write on various aspects of Shi‘ism, both from Ismaili and Twelver Shi‘i viewpoints, with scholarly vigour and enthusiasm. The most famous of his Ismaili compilations are Rawda-yi taslim, Sayr wa suluk, Tawalla wa tabarra, Akhlaq-i Muhtashimi and Matlub al-mu’minin. Tajrid al-i‘tiqad, al-Risala fi’l-imama and Fusul-i Nasiriyya are among his works dedicated to Twelver Shi‘ism.

In the Mongol court, Tusi witnessed the fall of the ‘Abbasid caliphate and after a while, securing the trust of Hulegu, the Mongol chief, he was given the full authority of administering the finances of religious foundations (awqaf). During this period of his life, Tusi’s main concern was combating Mongol savagery, saving the life of innocent scholars and the establishment of one of the most important centres of learning in Maragha, Northwest Iran. The compilation of Musari‘at al-musari‘, the Awsaf al-ashraf and Talkis al-muhassal are the scholarly writings of Tusi in the final years of his life.

Tusi’s Writings

The ensemble of Tusi’s writings amounts to approximately 165 titles on a wide variety of subjects. Some of them are simply a page or even half a page, but the majority with few exceptions, are well prepared scholarly works on astronomy, ethics, history, jurisprudence, logic, mathematics, medicine, philosophy, theology, poetry and the popular sciences. Tusi’s fame in his own lifetime guaranteed the survival of almost all of his scholarly output. The adverse effect of his fame is also the attribution of a number of works which neither match his style nor has the quality of his writings.

Tusi’s major works: (1) Astronomy: al-Tadhkira fi ‘ilm al-hay’a; Zij Ilkhani; Risala-yi Mu‘iniyya and its commentary. (2) Ethics: Gushayish-nama; Akhlaq-i Muhtashami; Akhlaq-i Nasiri, ‘Deliberation 22’ in Rawda-yi taslim and a Persian translation of Ibn Muqaffa‘’s al-Adab al-wajiz. (3) History: Fath-i Baghdad which appears as an appendix to Tarikh-i Jahan-gushay of Juwayni (London, 1912-27), vol. 3, pp. 280-92. (4) Jurisprudence: Jawahir al-fara’id. (5) Logic: Asas al-iqtibas. (6) Mathematics: Revision of Ptolemy’s Almagest; the epistles of Theodosius, Hypsicles, Autolucus, Aristarchus, Archimedes, Menelaus, Thabit b. Qurra and Banu Musa. (7) Medicine: Ta‘liqa bar qunun-i Ibn Sina and his correspondences with Qutb al-Din Shirazi and Katiban Qazwini. (8) Philosophy: refutation of al-Shahrastani in Musara‘at al-musari‘; his commentary on Ibn Sina’s al-Isharat wa’l-tanbihat which took him almost 20 years to complete; his autobiography Sayr wa suluk; Rawda-yi taslim and Tawalla wa tabarra. (9) Theology: Aghaz wa anjam; Risala fi al-imama and Talkhis al-muhassal and (10) Poetry: Mi‘yar al-ash‘ar.

http://iis.ac.uk/view_article.asp?ContentID=104813&l=en

Nasir al-Din Tusi

-

shiraz.virani

- Posts: 1256

- Joined: Thu May 28, 2009 2:52 pm

The works of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi illustrate the high level of intellectual life at Alamut

Posted by Nimira Dewji

Nasir al-Din Tusi, one of the major intellectual scholars of the thirteenth century, who contributed to many fields of learning, was born on February 18, 1201 in Tus, northeastern Persia into a Twelver Shi’i (Ithna’ashari) family. His father, a jurist, encourage al-Tusi to study a range of intellectual disciplines.

In his autobiographical work Sayr wa suluk (‘Contemplation and Action‘), al-Tusi “gives a brief account of his intellectual growth. After mastering all the sciences of his day, from theology and philosophy to mathematics and astronomy, Tusi remained dissatisfied, feeling that he was no nearer the truth [that he had been searching for] than before. What frustrated him more than anything else was the great diversity of opinions he encountered on the most basic issues of life and faith. But there was one school of thought that he had not yet explored, and that belonged to the Ismailis. He communicated his inquiries to the Ismaili governor of Quhistan, Shihab al-Din, and later met him briefly… Then he chanced to come across some sermons of Imam Hasan II [ala dhikrihi’l-salam (d. 1166)]. This discovery had such an impact on Tusi that around 1224 he converted to Ismailism” (Willey, Eagles Nest p 67-68).

Shortly thereafter, al-Tusi joined the service of the new Ismaili governor of Quhistan, Naser al-Din Mohtasham, as a resident scholar at the Ismaili fortress of Qa’in.

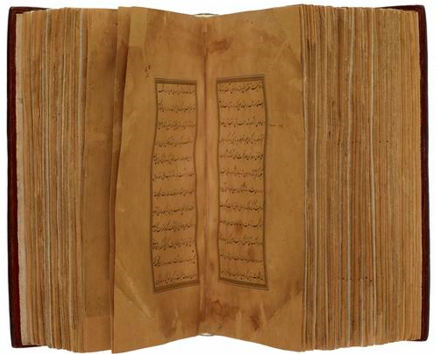

Qa'in Alamut Persia Iran Wiley

Fortress of Qa’in. Source: Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest

The governor was himself highly learned and encouraged Tusi in his philosophical and scientific researches. “Among the several works Tusi produced here, the most famous is Akhlaq-e Naseri (‘The Nasirean Ethics‘), a masterly synthesis of Neoplatonic and Islamic philosophy. After ten years of scholarship at Qa’in, Tusi was invited to go to Alamut. He could now avail himself freely of the rich resources of the Alamut library and also work with other scholars under the patronage of the Imam Ala al-Din Mohammad [r. 1221-1255]. The next twenty years were the most productive of Tusi’s life, during which time he produced a large number of books on philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, and the applied sciences…. In addition to his scientific works, Tusi composed a number of specifically Ismaili works, including Rawda-yi taslim (‘Paradise of Submission‘), a comprehensive philosophical exposition of Ismaili doctrines…” (Eagle’s Nest p 66-67).

al-tusi rawda-yi taslim paradise submission alamut

Source: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

The works of Tusi “well illustrate the significance of Ismaili intellectual and cultural life in the early decades of the 13th century, and the role of Alamut in encouraging the advancement of knowledge. As Marshall Hodgson describes it:

“…what was most distinctive was the high level of intellectual life. The prominent early Ismailis were commonly known as scholars, often as astronomers, and at least some later Ismailis continued the tradition. In Alamut, in Khusistan, and in Syria, at the main centres at least were libraries… which were well known among Sunni scholar… the Ismailis prized sophisticated interpretations of their own doctrines, and were also interested in every kind of knowledge which the age could offer” (Eagles Nest p 67-68).

After the Mongol conquest of Alamut in 1256, Tusi served as the scientific adviser to the Mongol leader Hulegu, who financially supported the construction of the most advanced observatory at Maragha (in present day Azerbaijan). Tusi worked at the observatory, producing the most influential works in astronomy and mathematics, as well as Ithna’ashari theology, indicating his return to Ithna’ashari Shi’ism (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 147).

Al-Tusi astronomy Alamut

Source: Alchetron

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi died in Baghdad in 1274. “He left an enduring intellectual legacy for Ismaili and Ithna’ashari Shi’ism as well as for all scholars of ethics, logic, mathematics, metaphysics, and theology” (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 147).

[email protected]

Sources:

Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2005

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Encyclopaedia Britannica

Jalal Badakhchani, Paradise of Submission, Synopsis, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Aziz Merchant, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi and Astronomy, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Farhad Daftary, Zulfikar Hirji, The Ismailis An Illustrated History, Azimuth Editions in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Totally History

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/02/15/the-works-of-nasir-al-din-al-tusi-illustrate-the-high-level-of-intellectual-life-at-alamut/

Posted by Nimira Dewji

Nasir al-Din Tusi, one of the major intellectual scholars of the thirteenth century, who contributed to many fields of learning, was born on February 18, 1201 in Tus, northeastern Persia into a Twelver Shi’i (Ithna’ashari) family. His father, a jurist, encourage al-Tusi to study a range of intellectual disciplines.

In his autobiographical work Sayr wa suluk (‘Contemplation and Action‘), al-Tusi “gives a brief account of his intellectual growth. After mastering all the sciences of his day, from theology and philosophy to mathematics and astronomy, Tusi remained dissatisfied, feeling that he was no nearer the truth [that he had been searching for] than before. What frustrated him more than anything else was the great diversity of opinions he encountered on the most basic issues of life and faith. But there was one school of thought that he had not yet explored, and that belonged to the Ismailis. He communicated his inquiries to the Ismaili governor of Quhistan, Shihab al-Din, and later met him briefly… Then he chanced to come across some sermons of Imam Hasan II [ala dhikrihi’l-salam (d. 1166)]. This discovery had such an impact on Tusi that around 1224 he converted to Ismailism” (Willey, Eagles Nest p 67-68).

Shortly thereafter, al-Tusi joined the service of the new Ismaili governor of Quhistan, Naser al-Din Mohtasham, as a resident scholar at the Ismaili fortress of Qa’in.

Qa'in Alamut Persia Iran Wiley

Fortress of Qa’in. Source: Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest

The governor was himself highly learned and encouraged Tusi in his philosophical and scientific researches. “Among the several works Tusi produced here, the most famous is Akhlaq-e Naseri (‘The Nasirean Ethics‘), a masterly synthesis of Neoplatonic and Islamic philosophy. After ten years of scholarship at Qa’in, Tusi was invited to go to Alamut. He could now avail himself freely of the rich resources of the Alamut library and also work with other scholars under the patronage of the Imam Ala al-Din Mohammad [r. 1221-1255]. The next twenty years were the most productive of Tusi’s life, during which time he produced a large number of books on philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, and the applied sciences…. In addition to his scientific works, Tusi composed a number of specifically Ismaili works, including Rawda-yi taslim (‘Paradise of Submission‘), a comprehensive philosophical exposition of Ismaili doctrines…” (Eagle’s Nest p 66-67).

al-tusi rawda-yi taslim paradise submission alamut

Source: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

The works of Tusi “well illustrate the significance of Ismaili intellectual and cultural life in the early decades of the 13th century, and the role of Alamut in encouraging the advancement of knowledge. As Marshall Hodgson describes it:

“…what was most distinctive was the high level of intellectual life. The prominent early Ismailis were commonly known as scholars, often as astronomers, and at least some later Ismailis continued the tradition. In Alamut, in Khusistan, and in Syria, at the main centres at least were libraries… which were well known among Sunni scholar… the Ismailis prized sophisticated interpretations of their own doctrines, and were also interested in every kind of knowledge which the age could offer” (Eagles Nest p 67-68).

After the Mongol conquest of Alamut in 1256, Tusi served as the scientific adviser to the Mongol leader Hulegu, who financially supported the construction of the most advanced observatory at Maragha (in present day Azerbaijan). Tusi worked at the observatory, producing the most influential works in astronomy and mathematics, as well as Ithna’ashari theology, indicating his return to Ithna’ashari Shi’ism (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 147).

Al-Tusi astronomy Alamut

Source: Alchetron

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi died in Baghdad in 1274. “He left an enduring intellectual legacy for Ismaili and Ithna’ashari Shi’ism as well as for all scholars of ethics, logic, mathematics, metaphysics, and theology” (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 147).

[email protected]

Sources:

Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2005

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Encyclopaedia Britannica

Jalal Badakhchani, Paradise of Submission, Synopsis, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Aziz Merchant, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi and Astronomy, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Farhad Daftary, Zulfikar Hirji, The Ismailis An Illustrated History, Azimuth Editions in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Totally History

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/02/15/the-works-of-nasir-al-din-al-tusi-illustrate-the-high-level-of-intellectual-life-at-alamut/

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi was profoundly impacted by the writings of Imam Ala Dhikrihi al-Salaam

Posted by Nimira Dewji

Nasir al-Din Tusi, one of the major intellectual scholars of the thirteenth century who contributed to many fields of learning, was born in 1201 in Tus, northeastern Persia into a Twelver Shi’i (Ithna’ashari) family. His father, a prominent jurist, encouraged al-Tusi to study all branches of knowledge and examine the views on the various schools of Islamic tradition, because his father “was not altogether satisfied with a purely prescriptive approach to the faith” (Badakhchani, Contemplation and Action p 1). Al-Tusi acquired an enduring thirst for knowledge, travelling far and wide in search of it.

In his autobiographical work Sayr wa suluk (‘Contemplation and Action‘), al-Tusi recounts his early education, search for knowledge, and eventual conversion to the Ismaili faith. It is also a discussion of the Ismaili doctrine of ta’lim, the need for an authoritative teacher in acquiring spiritual knowledge.

Contemplation-Action

“When I first embarked on [the study of] theology, I found a science which was entirely confined to practices of the exoteric side of the shari’at. Its practitioners seemed to force the intellect to promote a doctrine in which they blindly imitated their ancestors, cunningly deducing proofs and evidence for its validity, and devising excuses for the absurdities and contradictions which their doctrine necessarily entailed” (SS 9).

Continuing to ponder further, al-Tusi gradually realised that “since mankind is divided in its great diversity of opinions, the attainment of the truth is not possible through intellect and reason alone but required the additional intervention of a mukammil, an agent of perfection, an authoritative instructor or preceptor who is aware of such knowledge in its very essence.” He began to inquire “into the main propagators of this doctrine, the Ismailis … ” (Badakhchani, Contemplation and Action p 3).

One day, al-Tusi came across a compilation of the Fusul-i muqaddas (‘Sacred Chapters’), the sermons and sayings of Imam Hasan Ala Dhikrihi al-Salam (d. 1166), which impacted him profoundly:

“…I occupied myself day and night at reading it, and to the extent of my humble understanding and ability, I gained endless benefits from those sacred words which are the light of hearts and the illuminator of inner thoughts. It opened a little my eye of exploration… and my inner sight… was unveiled” (SS 15).

“Thereafter, my only desire was to introduce myself among the jama’at1 when the opportunity presented itself” (SS 16).

Following his own persistence as well as the intervention of the Ismaili governor of Quhistan, Nasir al-Din Muhtashim (d. 1257), al-Tusi was admitted as a mustajib (novice) into the Ismaili community. Shortly thereafter, al-Tusi joined the service of the governor, thus beginning his close association with the Ismaili leadership which was to continue for more than thirty years of his life.

“Now that I have come to know that unique person who is the man of the epoch, the Imam of the Age, the teacher of the followers of ta’lim, the locus of the word, he who enables one to recognise God – praise be to Him – and now that I have surrendered to the fact he is the [real] instructor, the truthful one, the ruler (hakim), I have attained the status of submission, utterly abandoned my own will, and arrived at the realm of learning and subjection” (Muslim Devotional Literature p 96).

After staying in Quhistan for ten years, al-Tusi went to Alamut, the seat of the Ismaili Imams, where he worked for twenty years; it was “the most productive period of his life. His creativity seems to have flourished under the patronage of Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad (d. 1255) and the elite of the Ismaili community of the time. Al-Tusi completed the most important of his philosophical works on Ismaili thought, Rawda-yi taslim (Paradise of Submission) in 1242, and Asas al-iqtibas (Principles of Acquisition) in 1244” (Badakhchani, Contemplation and Action p 6), as well as numerous works on astronomy.

A good portion of al-Tusi’s works produced during his association with the Ismailis has survived, whereas nothing has been preserved from, for example, the numerous writings of Imam Nur al-Din Muhammad (d. 1210) which was very popular at the time. Among other factors, the survival of Tusi’s works was undoubtedly due to the scholarly appeal of his writings, which brought him fame in his own lifetime.” (Badakhchani, Contemplation and Action p 19).

Most of al-Tusi’s works were not addressed to a specifically Ismaili audience, therefore they were likely circulated freely among the scholars of all communities before and after the fall of Alamut. “It is on the basis of these works, concerned essentially with issues and questions of interest to Muslim intellectuals in general and all those seeking knowledge, that Tusi’s considerable reputation as a scholar is founded. However, many of these works retain a certain Ismaili outlook and orientation” (Badakhchani, Contemplation and Action p 16).

Sources agree that during his long association with the Ismailis, Tusi wrote a number of Ismaili treatises that have either not survived or their Ismaili orientation may have been altered by later scholars or scribes to adapt them to the Twelver Shi’i milieu. “An example of such an amended text is Risala-yi jabr wa qadar (Treatise on Free Will and Predestination), a philosophical work in which quotations from the Fusul-i muqqadas of Imam Hasan Ala Dhikrihi al-Salam have been removed. Al-Dustur wa da’wat al-mu’minin li al-hudur (Notebook for Summoning the Faithful to the Present Imam) is another treatise which, although attributed by the compiler to Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad, is almost certainly the work of Tusi himself. It gives a detailed account of the ceremonies conducted for conversion to the Ismaili faith, which is described as ‘the religion of the theosophers and those travelling in the path of the scholars of divinity, who are followers of the House of Prophethood’” (Ibid).

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi died in Baghdad in 1274. “He left an enduring intellectual legacy for Ismaili and Ithna’ashari Shi’ism as well as for all scholars of ethics, logic, mathematics, metaphysics, and theology” (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 147).

Sources:

1 Literally assembly, congregation or community. In Ismaili literature, from the early Alamut period, this word is always used for the Ismaili community in particular. Contemplation and Action, Edited and translated by S.J. Badakhchani, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 1999 (p 67 n 13)

Secondary Curriculum Muslim Devotional and Ethical Literature, The Institute of Ismaili Studies p 96

Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2005

Farhad Daftary, Zulfikar Hirji, The Ismailis An Illustrated History, Azimuth Editions in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/07/25/nasir-al-din-al-tusi-was-influenced-by-the-writings-of-imam-ala-dhikrihi-al-salaam/

Posted by Nimira Dewji

Nasir al-Din Tusi, one of the major intellectual scholars of the thirteenth century who contributed to many fields of learning, was born in 1201 in Tus, northeastern Persia into a Twelver Shi’i (Ithna’ashari) family. His father, a prominent jurist, encouraged al-Tusi to study all branches of knowledge and examine the views on the various schools of Islamic tradition, because his father “was not altogether satisfied with a purely prescriptive approach to the faith” (Badakhchani, Contemplation and Action p 1). Al-Tusi acquired an enduring thirst for knowledge, travelling far and wide in search of it.

In his autobiographical work Sayr wa suluk (‘Contemplation and Action‘), al-Tusi recounts his early education, search for knowledge, and eventual conversion to the Ismaili faith. It is also a discussion of the Ismaili doctrine of ta’lim, the need for an authoritative teacher in acquiring spiritual knowledge.

Contemplation-Action

“When I first embarked on [the study of] theology, I found a science which was entirely confined to practices of the exoteric side of the shari’at. Its practitioners seemed to force the intellect to promote a doctrine in which they blindly imitated their ancestors, cunningly deducing proofs and evidence for its validity, and devising excuses for the absurdities and contradictions which their doctrine necessarily entailed” (SS 9).

Continuing to ponder further, al-Tusi gradually realised that “since mankind is divided in its great diversity of opinions, the attainment of the truth is not possible through intellect and reason alone but required the additional intervention of a mukammil, an agent of perfection, an authoritative instructor or preceptor who is aware of such knowledge in its very essence.” He began to inquire “into the main propagators of this doctrine, the Ismailis … ” (Badakhchani, Contemplation and Action p 3).

One day, al-Tusi came across a compilation of the Fusul-i muqaddas (‘Sacred Chapters’), the sermons and sayings of Imam Hasan Ala Dhikrihi al-Salam (d. 1166), which impacted him profoundly:

“…I occupied myself day and night at reading it, and to the extent of my humble understanding and ability, I gained endless benefits from those sacred words which are the light of hearts and the illuminator of inner thoughts. It opened a little my eye of exploration… and my inner sight… was unveiled” (SS 15).

“Thereafter, my only desire was to introduce myself among the jama’at1 when the opportunity presented itself” (SS 16).

Following his own persistence as well as the intervention of the Ismaili governor of Quhistan, Nasir al-Din Muhtashim (d. 1257), al-Tusi was admitted as a mustajib (novice) into the Ismaili community. Shortly thereafter, al-Tusi joined the service of the governor, thus beginning his close association with the Ismaili leadership which was to continue for more than thirty years of his life.

“Now that I have come to know that unique person who is the man of the epoch, the Imam of the Age, the teacher of the followers of ta’lim, the locus of the word, he who enables one to recognise God – praise be to Him – and now that I have surrendered to the fact he is the [real] instructor, the truthful one, the ruler (hakim), I have attained the status of submission, utterly abandoned my own will, and arrived at the realm of learning and subjection” (Muslim Devotional Literature p 96).

After staying in Quhistan for ten years, al-Tusi went to Alamut, the seat of the Ismaili Imams, where he worked for twenty years; it was “the most productive period of his life. His creativity seems to have flourished under the patronage of Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad (d. 1255) and the elite of the Ismaili community of the time. Al-Tusi completed the most important of his philosophical works on Ismaili thought, Rawda-yi taslim (Paradise of Submission) in 1242, and Asas al-iqtibas (Principles of Acquisition) in 1244” (Badakhchani, Contemplation and Action p 6), as well as numerous works on astronomy.

A good portion of al-Tusi’s works produced during his association with the Ismailis has survived, whereas nothing has been preserved from, for example, the numerous writings of Imam Nur al-Din Muhammad (d. 1210) which was very popular at the time. Among other factors, the survival of Tusi’s works was undoubtedly due to the scholarly appeal of his writings, which brought him fame in his own lifetime.” (Badakhchani, Contemplation and Action p 19).

Most of al-Tusi’s works were not addressed to a specifically Ismaili audience, therefore they were likely circulated freely among the scholars of all communities before and after the fall of Alamut. “It is on the basis of these works, concerned essentially with issues and questions of interest to Muslim intellectuals in general and all those seeking knowledge, that Tusi’s considerable reputation as a scholar is founded. However, many of these works retain a certain Ismaili outlook and orientation” (Badakhchani, Contemplation and Action p 16).

Sources agree that during his long association with the Ismailis, Tusi wrote a number of Ismaili treatises that have either not survived or their Ismaili orientation may have been altered by later scholars or scribes to adapt them to the Twelver Shi’i milieu. “An example of such an amended text is Risala-yi jabr wa qadar (Treatise on Free Will and Predestination), a philosophical work in which quotations from the Fusul-i muqqadas of Imam Hasan Ala Dhikrihi al-Salam have been removed. Al-Dustur wa da’wat al-mu’minin li al-hudur (Notebook for Summoning the Faithful to the Present Imam) is another treatise which, although attributed by the compiler to Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad, is almost certainly the work of Tusi himself. It gives a detailed account of the ceremonies conducted for conversion to the Ismaili faith, which is described as ‘the religion of the theosophers and those travelling in the path of the scholars of divinity, who are followers of the House of Prophethood’” (Ibid).

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi died in Baghdad in 1274. “He left an enduring intellectual legacy for Ismaili and Ithna’ashari Shi’ism as well as for all scholars of ethics, logic, mathematics, metaphysics, and theology” (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 147).

Sources:

1 Literally assembly, congregation or community. In Ismaili literature, from the early Alamut period, this word is always used for the Ismaili community in particular. Contemplation and Action, Edited and translated by S.J. Badakhchani, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 1999 (p 67 n 13)

Secondary Curriculum Muslim Devotional and Ethical Literature, The Institute of Ismaili Studies p 96

Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London, 2005

Farhad Daftary, Zulfikar Hirji, The Ismailis An Illustrated History, Azimuth Editions in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/07/25/nasir-al-din-al-tusi-was-influenced-by-the-writings-of-imam-ala-dhikrihi-al-salaam/

Book Review by Alyjan Daya

Nair al-Din Tusi;: A Philosopher for All Seasons

by Sayeh Meisami, Cambridge, Islamic Texts Society, 2019, 128 pp., £12.99 (paperback), ISBN 978-1-911141-23-5

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10 ... ccess=true

Nair al-Din Tusi;: A Philosopher for All Seasons

by Sayeh Meisami, Cambridge, Islamic Texts Society, 2019, 128 pp., £12.99 (paperback), ISBN 978-1-911141-23-5

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10 ... ccess=true

Re: Nasir al-Din Tusi

The writings of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi illustrate the high level of intellectual life at the Nizari Ismaili fortress of Alamut

BY NIMIRA DEWJI POSTED ON FEBRUARY 17, 2022

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tusi, better known as Nasir al-Din Tusi, one of the major intellectual scholars of the thirteenth century who contributed to many fields of learning, was born on 18 February 1201 in Tus, northeastern Persia, into a Twelver Shi’i (Ithna’ashari) family. His father, a jurist, encouraged al-Tusi to study a range of intellectual disciplines.

In his autobiographical work Sayr wa suluk (‘Contemplation and Action‘), al-Tusi “gives a brief account of his intellectual growth. After mastering all the sciences of his day, from theology and philosophy to mathematics and astronomy, Tusi remained dissatisfied, feeling that he was no nearer the truth [that he had been searching for] than before. What frustrated him more than anything else was the great diversity of opinions he encountered on the most basic issues of life and faith. But there was one school of thought that he had not yet explored, and that belonged to the Ismailis.” (Willey, Eagles Nest p 67-68).

Image: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Continuing to ponder further, al-Tusi gradually realised that “since mankind is divided in its great diversity of opinions, the attainment of the truth is not possible through intellect and reason alone but required the additional intervention of a mukammil, an agent of perfection, an authoritative instructor or preceptor who is aware of such knowledge in its very essence.” He began to inquire “into the main propagators of this doctrine, the Ismailis … ” (Badakhchani, Contemplation and Action p 3).

Then he chanced to come across some sermons of Imam Hasan II [ala dhikrihi’l-salam [d. 1166]. This discovery had such an impact on Tusi that around 1224 he converted to Ismailism” (Willey, Eagles Nest p 67-68). He communicated his inquiries to the Ismaili governor of Quhistan, Shihab al-Din, and later met him briefly… ” (Willey, Eagles Nest p 67-68).

Shortly thereafter, al-Tusi joined the service of the new Ismaili governor of Quhistan, Naser al-Din Mohtasham, as a resident scholar at the fortress of Qa’in, one of the several strongholds acquired by the Nizari Ismailis of Alamut.

Fortress of Qa’in. Image: Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest

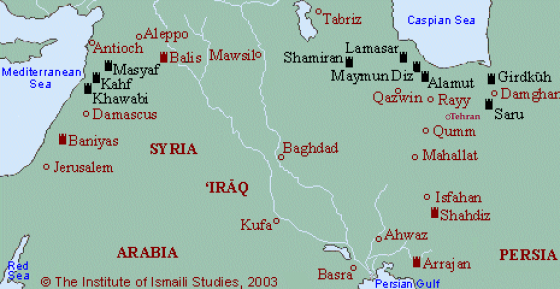

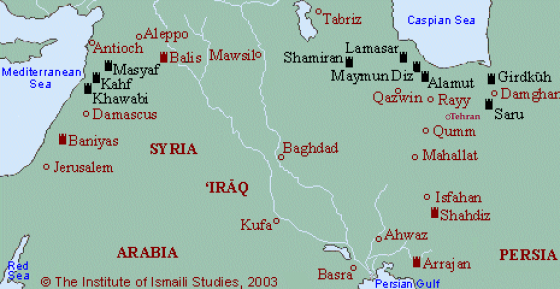

Nizari Ismaili State of Alamut

In 1090, Hasan Sabbah acquired the fortress of Alamut in northern Iran, marking the founding of what was to become the seat of the Nizari Ismaili state. Over the next 150 years, the Ismailis acquired more than 200 fortresses in Iran and Syria, located in the inaccessible mountainous regions for refuge of the Nizari Ismailis fleeing persecution by the Saljuqs and other rulers during the early Middle Ages. These settlements were also a sanctuary for other refugees, irrespective of their creed, fleeing persecution.

li Castles in Iran and Syria. Image via IIS

Ismaili fortresses in Iran and Syria. Image: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

The Nizari Ismailis of the Alamut period placed a high value on intellectual activities despite having to defend against military attacks. Alamut and several of the Nizari strongholds became flourishing centres of intellectual activities with major libraries containing not only a significant collection of books and documents but also scientific tracts and equipment. The Ismailis extended their patronage of learning to everyone.

Alamut

The back of the fortress of Alamut which provided the only entrance to the castle. Hasan Sabbah constructed huge underground storage chambers to keep the garrison in food water during times of siege. The Institute of Ismaili Studies

The ruins of the fortresses, especially their water supply systems, are evidence of the ingenious methods adopted by the Persian Nizaris for coping with highly difficult living conditions. Although much of the literature produced by the Nizaris during this time was destroyed by the Mongols, the accounts of some later Persian historians provide information about the community during this period; only a few non-literary items such as coins minted at Alamut have survived.

Archaeological excavations at some of the sites of the castles of Alamut discovered a variety of kilns, some of which contained fragments of decorated dishes, water-pots, and oil lamps, among other items revealing the artistic skills f the Nizari Ismailis. However, much of the evidence has been removed as a result of land cultivation for agriculture.

Agate beads and fine moulded wares from Andej, Image: Eagle’s Nest

Al-Tusi at Qa’in

The governor of Qa’in was himself highly learned and encouraged Tusi in his philosophical and scientific researches. “Among the several works Tusi produced here, the most famous is Akhlaq-e Naseri (‘The Nasirean Ethics‘), a masterly synthesis of Neoplatonic and Islamic philosophy.

After ten years of scholarship at Qa’in, Tusi was invited to go to Alamut, the centre of the Ismaili da’wa and intellectual activities. He could now avail himself freely of the rich resources of the Alamut library and also work with other scholars under the patronage of Imam Ala al-Din Mohammad [r. 1221-1255].

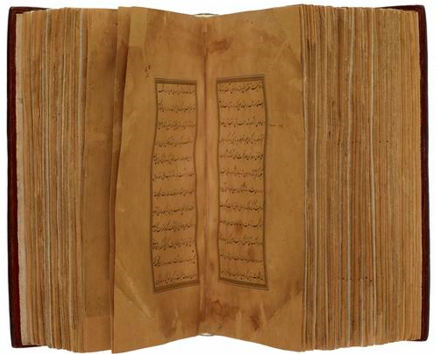

A Manuscript of Akhlaq-i Nasiri created for Nasir al-Din Abd al-Rahim, Lahore, Pakistan, ca. 1590-1595. Aga Khan Museum

The next twenty years were the most productive of Tusi’s life, during which time he produced a large number of books on philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, and the applied sciences…. In addition to his scientific works, Tusi composed a number of specifically Ismaili works, including Rawda-yi taslim (‘Paradise of Submission‘), a comprehensive philosophical exposition of Ismaili doctrines…” (Eagle’s Nest p 66-67). It is mainly through al-Tusi’s writings that modern scholars have come to have a better understanding of the Ismaili teachings of the Alamut period” (Daftary, The Ismaili Imams p 141).

The greatest expression of divine mercy to mankind is the appearance of the Imam of the Age

Image: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Peter Willey notes that the works of Tusi “well illustrate the significance of Ismaili intellectual and cultural life in the early decades of the 13th century, and the role of Alamut in encouraging the advancement of knowledge. As Marshall Hodgson describes it:

“…what was most distinctive was the high level of intellectual life. The prominent early Ismailis were commonly known as scholars, often as astronomers, and at least some later Ismailis continued the tradition. In Alamut, in Khusistan [Quhistan], and in Syria, at the main centres at least were libraries… which were well known among Sunni scholar… the Ismailis prized sophisticated interpretations of their own doctrines, and were also interested in every kind of knowledge which the age could offer” (Eagles Nest p 67-68).

Sources agree that during his long association with the Ismailis, Tusi wrote a number of Ismaili treatises that have either not survived or their Ismaili orientation may have been altered by later scholars or scribes to adapt them to the Twelver Shi’i milieu. “An example of such an amended text is Risala-yi jabr wa qadar (Treatise on Free Will and Predestination), a philosophical work in which quotations from the Fusul-i muqqadas of Imam Hasan Ala Dhikrihi al-Salam have been removed.” In his work Al-Dustur wa da’wat al-mu’minin li al-hudur (Notebook for Summoning the Faithful to the Present Imam) “al-Tusi describes the Ismaili faith as ‘the religion of the theosophers and those travelling in the path of the scholars of divinity, who are followers of the House of Prophethood’” (Badakhchani, Contemplation and Action p 16).

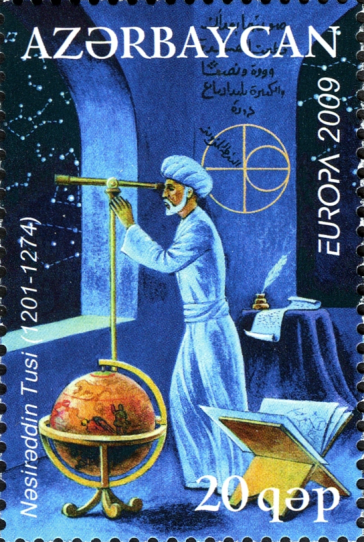

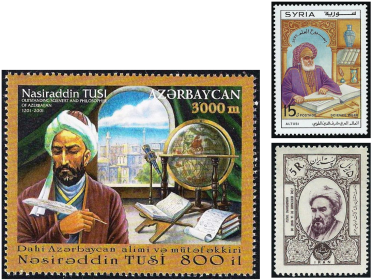

Post Alamut

After the Mongol conquest of Alamut in 1256, Tusi served as the scientific adviser to the Mongol leader Hulegu, who financially supported the construction of the most advanced observatory at Maragha (in present day Azerbaijan). Tusi worked at the observatory, producing the most influential works in astronomy and mathematics, as well as Ithna’ashari theology, indicating his return to Ithna’ashari Shi’ism (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 147).

Stamp issued in the republic of Azerbaijan in 2009 honoring Tusi. Image: Kh. Mirzoyev/Wikipedia

Al-Tusi made monumental contributions to mathematics, establishing trigonometry as an independent subject. He also create the most accurate tables to calculate planetary movements to determine the position of stars and planets and referenced until Copernicus developed one 250 years later. A lunar crater is named after al-Tusi in recognition of his contribution in the field of astronomy.

Stamps honouring Al-Tusi. Image: Alchetron

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi died in Baghdad in 1274. “He left an enduring intellectual legacy for Ismaili and Ithna’ashari Shi’ism as well as for all scholars of ethics, logic, mathematics, metaphysics, and theology” (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 147).

Islamic Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (ICESCO) List

The site of the fortress of Alamut and four Iranian monuments are registered on the ICESCO’s Islamic World Heritage List (February 2022). More at Tehran Times.

Further reading: Fabricated Medieval Tales

Sources:

Aziz Merchant, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi and Astronomy, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Farhad Daftary, Zulfikar Hirji, The Ismailis An Illustrated History, Azimuth Editions

Farhad Daftary, The Ismaili Imams, I.B. Tauris, London, 2009

Jalal Badakhchani, Paradise of Submission, Synopsis, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, I.B. Tauris, London, 2005

Rosalind A. Wade Haddon “Ismaili Pottery from the Alamut Period,” published in Eagle’s Nest, Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, Peter Willey, I.B. Tauris Publishers, London, 2005

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Encyclopaedia Britannica

Contributed to Ismailimail by Nimira Dewji. Nimira is an invited writer although she has contributed several articles in the past (view previous articles). She also has her own blog – Nimirasblog – where she writes short articles on Ismaili history and Muslim civilisations. When not researching and writing, Nimira volunteers at a shelter for the unhoused, and at a women’s shelter. She can be reached at [email protected].

ismailimail.blog/2022/02/17/the-writings-of-nasir-al-din-al-tusi-illustrate-the-high-level-of-intellectual-life-at-the-nizari-ismaili-fortress-of-alamut/

BY NIMIRA DEWJI POSTED ON FEBRUARY 17, 2022

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tusi, better known as Nasir al-Din Tusi, one of the major intellectual scholars of the thirteenth century who contributed to many fields of learning, was born on 18 February 1201 in Tus, northeastern Persia, into a Twelver Shi’i (Ithna’ashari) family. His father, a jurist, encouraged al-Tusi to study a range of intellectual disciplines.

In his autobiographical work Sayr wa suluk (‘Contemplation and Action‘), al-Tusi “gives a brief account of his intellectual growth. After mastering all the sciences of his day, from theology and philosophy to mathematics and astronomy, Tusi remained dissatisfied, feeling that he was no nearer the truth [that he had been searching for] than before. What frustrated him more than anything else was the great diversity of opinions he encountered on the most basic issues of life and faith. But there was one school of thought that he had not yet explored, and that belonged to the Ismailis.” (Willey, Eagles Nest p 67-68).

Image: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Continuing to ponder further, al-Tusi gradually realised that “since mankind is divided in its great diversity of opinions, the attainment of the truth is not possible through intellect and reason alone but required the additional intervention of a mukammil, an agent of perfection, an authoritative instructor or preceptor who is aware of such knowledge in its very essence.” He began to inquire “into the main propagators of this doctrine, the Ismailis … ” (Badakhchani, Contemplation and Action p 3).

Then he chanced to come across some sermons of Imam Hasan II [ala dhikrihi’l-salam [d. 1166]. This discovery had such an impact on Tusi that around 1224 he converted to Ismailism” (Willey, Eagles Nest p 67-68). He communicated his inquiries to the Ismaili governor of Quhistan, Shihab al-Din, and later met him briefly… ” (Willey, Eagles Nest p 67-68).

Shortly thereafter, al-Tusi joined the service of the new Ismaili governor of Quhistan, Naser al-Din Mohtasham, as a resident scholar at the fortress of Qa’in, one of the several strongholds acquired by the Nizari Ismailis of Alamut.

Fortress of Qa’in. Image: Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest

Nizari Ismaili State of Alamut

In 1090, Hasan Sabbah acquired the fortress of Alamut in northern Iran, marking the founding of what was to become the seat of the Nizari Ismaili state. Over the next 150 years, the Ismailis acquired more than 200 fortresses in Iran and Syria, located in the inaccessible mountainous regions for refuge of the Nizari Ismailis fleeing persecution by the Saljuqs and other rulers during the early Middle Ages. These settlements were also a sanctuary for other refugees, irrespective of their creed, fleeing persecution.

li Castles in Iran and Syria. Image via IIS

Ismaili fortresses in Iran and Syria. Image: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

The Nizari Ismailis of the Alamut period placed a high value on intellectual activities despite having to defend against military attacks. Alamut and several of the Nizari strongholds became flourishing centres of intellectual activities with major libraries containing not only a significant collection of books and documents but also scientific tracts and equipment. The Ismailis extended their patronage of learning to everyone.

Alamut

The back of the fortress of Alamut which provided the only entrance to the castle. Hasan Sabbah constructed huge underground storage chambers to keep the garrison in food water during times of siege. The Institute of Ismaili Studies

The ruins of the fortresses, especially their water supply systems, are evidence of the ingenious methods adopted by the Persian Nizaris for coping with highly difficult living conditions. Although much of the literature produced by the Nizaris during this time was destroyed by the Mongols, the accounts of some later Persian historians provide information about the community during this period; only a few non-literary items such as coins minted at Alamut have survived.

Archaeological excavations at some of the sites of the castles of Alamut discovered a variety of kilns, some of which contained fragments of decorated dishes, water-pots, and oil lamps, among other items revealing the artistic skills f the Nizari Ismailis. However, much of the evidence has been removed as a result of land cultivation for agriculture.

Agate beads and fine moulded wares from Andej, Image: Eagle’s Nest

Al-Tusi at Qa’in

The governor of Qa’in was himself highly learned and encouraged Tusi in his philosophical and scientific researches. “Among the several works Tusi produced here, the most famous is Akhlaq-e Naseri (‘The Nasirean Ethics‘), a masterly synthesis of Neoplatonic and Islamic philosophy.

After ten years of scholarship at Qa’in, Tusi was invited to go to Alamut, the centre of the Ismaili da’wa and intellectual activities. He could now avail himself freely of the rich resources of the Alamut library and also work with other scholars under the patronage of Imam Ala al-Din Mohammad [r. 1221-1255].

A Manuscript of Akhlaq-i Nasiri created for Nasir al-Din Abd al-Rahim, Lahore, Pakistan, ca. 1590-1595. Aga Khan Museum

The next twenty years were the most productive of Tusi’s life, during which time he produced a large number of books on philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, and the applied sciences…. In addition to his scientific works, Tusi composed a number of specifically Ismaili works, including Rawda-yi taslim (‘Paradise of Submission‘), a comprehensive philosophical exposition of Ismaili doctrines…” (Eagle’s Nest p 66-67). It is mainly through al-Tusi’s writings that modern scholars have come to have a better understanding of the Ismaili teachings of the Alamut period” (Daftary, The Ismaili Imams p 141).

The greatest expression of divine mercy to mankind is the appearance of the Imam of the Age

Image: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Peter Willey notes that the works of Tusi “well illustrate the significance of Ismaili intellectual and cultural life in the early decades of the 13th century, and the role of Alamut in encouraging the advancement of knowledge. As Marshall Hodgson describes it:

“…what was most distinctive was the high level of intellectual life. The prominent early Ismailis were commonly known as scholars, often as astronomers, and at least some later Ismailis continued the tradition. In Alamut, in Khusistan [Quhistan], and in Syria, at the main centres at least were libraries… which were well known among Sunni scholar… the Ismailis prized sophisticated interpretations of their own doctrines, and were also interested in every kind of knowledge which the age could offer” (Eagles Nest p 67-68).

Sources agree that during his long association with the Ismailis, Tusi wrote a number of Ismaili treatises that have either not survived or their Ismaili orientation may have been altered by later scholars or scribes to adapt them to the Twelver Shi’i milieu. “An example of such an amended text is Risala-yi jabr wa qadar (Treatise on Free Will and Predestination), a philosophical work in which quotations from the Fusul-i muqqadas of Imam Hasan Ala Dhikrihi al-Salam have been removed.” In his work Al-Dustur wa da’wat al-mu’minin li al-hudur (Notebook for Summoning the Faithful to the Present Imam) “al-Tusi describes the Ismaili faith as ‘the religion of the theosophers and those travelling in the path of the scholars of divinity, who are followers of the House of Prophethood’” (Badakhchani, Contemplation and Action p 16).

Post Alamut

After the Mongol conquest of Alamut in 1256, Tusi served as the scientific adviser to the Mongol leader Hulegu, who financially supported the construction of the most advanced observatory at Maragha (in present day Azerbaijan). Tusi worked at the observatory, producing the most influential works in astronomy and mathematics, as well as Ithna’ashari theology, indicating his return to Ithna’ashari Shi’ism (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 147).

Stamp issued in the republic of Azerbaijan in 2009 honoring Tusi. Image: Kh. Mirzoyev/Wikipedia

Al-Tusi made monumental contributions to mathematics, establishing trigonometry as an independent subject. He also create the most accurate tables to calculate planetary movements to determine the position of stars and planets and referenced until Copernicus developed one 250 years later. A lunar crater is named after al-Tusi in recognition of his contribution in the field of astronomy.

Stamps honouring Al-Tusi. Image: Alchetron

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi died in Baghdad in 1274. “He left an enduring intellectual legacy for Ismaili and Ithna’ashari Shi’ism as well as for all scholars of ethics, logic, mathematics, metaphysics, and theology” (The Ismailis An Illustrated History p 147).

Islamic Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (ICESCO) List

The site of the fortress of Alamut and four Iranian monuments are registered on the ICESCO’s Islamic World Heritage List (February 2022). More at Tehran Times.

Further reading: Fabricated Medieval Tales

Sources:

Aziz Merchant, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi and Astronomy, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Farhad Daftary, Zulfikar Hirji, The Ismailis An Illustrated History, Azimuth Editions

Farhad Daftary, The Ismaili Imams, I.B. Tauris, London, 2009

Jalal Badakhchani, Paradise of Submission, Synopsis, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, I.B. Tauris, London, 2005

Rosalind A. Wade Haddon “Ismaili Pottery from the Alamut Period,” published in Eagle’s Nest, Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria, Peter Willey, I.B. Tauris Publishers, London, 2005

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Encyclopaedia Britannica

Contributed to Ismailimail by Nimira Dewji. Nimira is an invited writer although she has contributed several articles in the past (view previous articles). She also has her own blog – Nimirasblog – where she writes short articles on Ismaili history and Muslim civilisations. When not researching and writing, Nimira volunteers at a shelter for the unhoused, and at a women’s shelter. She can be reached at [email protected].

ismailimail.blog/2022/02/17/the-writings-of-nasir-al-din-al-tusi-illustrate-the-high-level-of-intellectual-life-at-the-nizari-ismaili-fortress-of-alamut/