Jamatkhana Architecture

Jamatkhanas Adopting Environmentally Sustainable Practices

Going green has been a conscious effort made by those who keep Jamatkhanas running on a daily basis. The Council’s Property Matters Portfolio (PMP) is tasked to work closely with Jamati leaders to ensure the success of sustainability through new initiatives.

To reduce paper waste, Jamatkhanas have set up wi-fi and internet connections, created spaces for laptops and computers, and installed televisions or projectors to share announcements.

To save on energy, all LED lighting, low flow toilets, and sinks have been installed in Jamatkhanas. Every attempt has been made to use energy star or low energy-consuming equipment wherever possible.

To reduce plastic waste, reusable nandi bags have been provided as well as paper and recyclable products such as cups and napkins. Additionally, each Jamatkhana has introduced recycling programs.

For new construction, the PMP tries to use low-maintenance products, stronger building materials for longevity, and reduction of waste and landfill use, over time. To create building efficiency, natural lighting has been incorporated into the design of the space. Additionally, multi-pane Low-E windows, efficient HVAC systems, superior insulation, and smart technology are used, which collaboratively make the building as efficient as possible.

The PMP is also looking into LEED-certified Jamatkhanas for future construction projects. The team works continuously with local Jamatkhana leaders to educate them on resources we have available, the necessity of being environmentally responsible, and how they can help reduce our Jamatkhana footprint by adopting these practices. While more changes are coming, these sustainable initiatives are a great start.

https://the.ismaili/usa/our-community/j ... -practices

Going green has been a conscious effort made by those who keep Jamatkhanas running on a daily basis. The Council’s Property Matters Portfolio (PMP) is tasked to work closely with Jamati leaders to ensure the success of sustainability through new initiatives.

To reduce paper waste, Jamatkhanas have set up wi-fi and internet connections, created spaces for laptops and computers, and installed televisions or projectors to share announcements.

To save on energy, all LED lighting, low flow toilets, and sinks have been installed in Jamatkhanas. Every attempt has been made to use energy star or low energy-consuming equipment wherever possible.

To reduce plastic waste, reusable nandi bags have been provided as well as paper and recyclable products such as cups and napkins. Additionally, each Jamatkhana has introduced recycling programs.

For new construction, the PMP tries to use low-maintenance products, stronger building materials for longevity, and reduction of waste and landfill use, over time. To create building efficiency, natural lighting has been incorporated into the design of the space. Additionally, multi-pane Low-E windows, efficient HVAC systems, superior insulation, and smart technology are used, which collaboratively make the building as efficient as possible.

The PMP is also looking into LEED-certified Jamatkhanas for future construction projects. The team works continuously with local Jamatkhana leaders to educate them on resources we have available, the necessity of being environmentally responsible, and how they can help reduce our Jamatkhana footprint by adopting these practices. While more changes are coming, these sustainable initiatives are a great start.

https://the.ismaili/usa/our-community/j ... -practices

IRINGA JAMATKHANA

The life story of Mohamed Hamir

"a small man from Kutch with giant dreams for his community."

When one visits the Khoja Ismaili Jamatkhana in Iringa, there is a picture hanging on the wall as you go up the stairs. It is a picture of my maternal grandfather, Mohamed Hamir and my maternal grandmother, Bachibai Mohamed Hamir.

The writing states:

“In 1933, Alijah Mohamed Hamir Pradhan, on behalf of Hamir Family, unconditionally gifted the Iringa Jamatkhana to the Imam of the time Aga Khan III, Sultan Mohamed Shah. Also included in the building structure were the facilities for a primary school for use by the community."

The city of Iringa in the Southern Highland region of Tanzania, is 500 kilometres from the capital Dar es Salaam and sits along a hilltop overlooking the great Ruaha River, close to the Ruaha National Park , the country's second largest wildlife park.

"Iringa" means "fort" in the local Hehe language and is named for a German colonial centre built in 1900. (Left)

Mohamed Hamir Pradhan came from Kutch India around 1905-1906 to join his brothers, Haji and Sachedina (Satchu) Hamir, who had settled there towards the end of 19th century.

It is said that to earn his travel-fare, Mohamedbha worked as a masonry labourer in Bombay , the main British Indian steamship port of embarkation for Khoja migrants to Africa.

In Tanganyika, after working initially for his brothers and after learning to speak Kiswahili, he went deep into the Southern Highland region to start a small retail clothing duka-shop.

Many Khojas traders had settled in Iringa after 1896, when the German Captain Tom Prince, a soldier-farmer opened the region for European farming (see The Intrepid East African Dukawalla. Ed.)

Over the next two decades, his business became very successful. During and after the First World War, he established good relationships with the German and later British administrators in Iringa and benefited from the war economy.

Mohamed Hamir was a person with strong religious beliefs and community commitment. Towards the of 1929, he expressed to the small Khoja Ismaili Community of Iringa, his desire to build a new Jamatkhana- community center and he personally pledged Shs 40,000/= towards the projected total cost of Shs 60,000 - 65,000. He proposed an ambitious plan to accommodate future settlement in the area, with the new building to seat between 500 to 600 members (the Ismaili population in Iringa at that time, was quite small) and to have primary school as well as sport facilities on the same premises within the compound.

Following the presentation of the proposal to the Ismaili members, Nasser Dossa & Somji Pradhan pledged to donate the land and he personally pledged shs. 40,000 towards the projected total building cost of 60,000 - 65,000 shs. He proposed an ambitious plan to accommodate future settlement in the area, with the new building to seat between 500 to 600 members (the Ismaili population in Iringa at that time was quite small) and to have a primary school as well as sport facilities on the same premises within a compound area.

Because of his previous experience in building work, Mohamedbha had all the design plans ready and he also personally volunteered to be its supervisor, choosing to work with two Hindu "mistrys" named Dewji and Nagji. After many political battles with regards to design and funding, other prominent Ismailis finally pledged the rest of the money for the building, to be paid after the sum of Mohamedbha's initial contribution was spent.

The plan was for a beautiful three-level building with a ground floor and two upper stories halls. The first story to be the main prayer-hall and the second floor to be for a meditation hall baitulkhayal for the intense prayer group. The design was based on the Jamatkhana in Bhuj, in his native Kutch.

After completion of the first floor, Mohamedbha's funds were used up and when he requested the others for their pledged contributions, for various reasons, they were not able to fulfill their commitments. So he had to modify the building plans, deleting the third floor and also having to complete the whole project on his own. He was forced to borrow money from other families he knew outside Iringa who had also come from Kutch.

As per my mother and his daughter, Rehmat Fazal Manji (nee Hamir), and information from my cousin, Diamond Akber Mohamed Hamir (his grandson) and Sikinabai Kanji Lalji, the families who helped him at this time were Kanji Lalji of Mbeya (my father, Fazal Manji Lalji’s uncle) and Dhalla Bhimji of Dar es Salaam.

He also requested a Hindu merchant to supply the building cement on credit with a verbal promise to pay him whenever he could. He pledged to this merchant by "submitting" his pagri (headgear) to the merchant - an Indian custom when one has to borrow money on their "word" and without collateral. For this good cause,the merchant promised to supply as much building materials as needed on credit and respectfully requested Mohamedbha to take back his “pagri”.

In Dar es Salaam, the Darkhana Jamatkhana was also being built around the same time and it too had plans to install a clock tower. Mohamedbha had placed an order for the clock at the same time as the Dar es Salaam order, as they were similar clocks and were being bought from a London company. It so happened that the clock for Dar es Salaam was delayed in manufacturing but the Iringa clock had arrived. Since the Dar es Salaam was scheduled to be opened earlier then Iringa, so following a request from the Dar es Salaam building committee, Mohamedbha generously offered his clock and thus it was installed for the Dar es Salaam Jamatkhana to be ready for the opening ceremony in the early 1930’s. It took about another 6 months for the Iringa clock to arrive

TAAN,MAAN,DHAN - A CASE OF TOTAL CHARITY

With his a masonry experience and to save labour cost, Mohamedbha did the masonry work himself (as seen in the front part of the building in the photos above and the photo on the right) .

His home and duka was next door to Jamatkhana construction site and he used to do work there with the help of his wife, Bachibai after evening prayers and dinner until late in the night. The lighting was provided by kerosene lanterns.

In 1933, with help of Bachibai, the help of Khoja Ismaili families who lent him the extra money and that his Hindu merchant supplier, Mohamed Hamir was able to finish the iconic building, including a large clock tower, at a total cost of Shs 63,000 plus (which equals to approximately US $250,00 in current value), a princely sum during The Great Depression !

Mohamedbha not only paid all the lenders and merchants fully in following few years but he also added another Shs 9,000 donation towards the building of the school to provide access to education to the children of the community as there was no government or community school at that time and so a primary school was established on the ground floor of the building.

UNCONDITIONAL DONATION AND REWARD

In 1933, on behalf of the Hamir family, he unconditionally gifted the Iringa Jamatkhana to the Ismaili Imam of the time, Aga Khan lll. The Imam bestowed him with title of Alijah, granted him an audience and formally accepted the gift during his Golden Jubilee celebrations in Dar es Salaam in 1936.

A TIMELESS LEGACY

Mohamed Hamir was a bold, forward-thinking and dedicated gentleman. He also had the fore-sight to build a Jamatkhana larger than needed at that time. Some 25 years later, the building was modified to accommodate a larger jamaat of Iringa (community had grown five-folds) and it was his only son, Alijah Akber Mohamed Hamir who assisted in the expansion project.

Alijah Mohamed Hamir, who passed away in 1943 and was buried in Iringa, left us an iconic Kutchi landmark in a small town in Tanganyika, a clock for all the town-people to keep time, a a school, community centre and meditation hall for his jamaat to benefit, a beautiful architectural structure for the country and one of the more beautiful jamatkhanas in the world - a very proud legacy for the entire Hamir family and a humbling experience for his grandson to write about it.

https://myemail.constantcontact.com/-De ... 3l-960KlYE

The life story of Mohamed Hamir

"a small man from Kutch with giant dreams for his community."

When one visits the Khoja Ismaili Jamatkhana in Iringa, there is a picture hanging on the wall as you go up the stairs. It is a picture of my maternal grandfather, Mohamed Hamir and my maternal grandmother, Bachibai Mohamed Hamir.

The writing states:

“In 1933, Alijah Mohamed Hamir Pradhan, on behalf of Hamir Family, unconditionally gifted the Iringa Jamatkhana to the Imam of the time Aga Khan III, Sultan Mohamed Shah. Also included in the building structure were the facilities for a primary school for use by the community."

The city of Iringa in the Southern Highland region of Tanzania, is 500 kilometres from the capital Dar es Salaam and sits along a hilltop overlooking the great Ruaha River, close to the Ruaha National Park , the country's second largest wildlife park.

"Iringa" means "fort" in the local Hehe language and is named for a German colonial centre built in 1900. (Left)

Mohamed Hamir Pradhan came from Kutch India around 1905-1906 to join his brothers, Haji and Sachedina (Satchu) Hamir, who had settled there towards the end of 19th century.

It is said that to earn his travel-fare, Mohamedbha worked as a masonry labourer in Bombay , the main British Indian steamship port of embarkation for Khoja migrants to Africa.

In Tanganyika, after working initially for his brothers and after learning to speak Kiswahili, he went deep into the Southern Highland region to start a small retail clothing duka-shop.

Many Khojas traders had settled in Iringa after 1896, when the German Captain Tom Prince, a soldier-farmer opened the region for European farming (see The Intrepid East African Dukawalla. Ed.)

Over the next two decades, his business became very successful. During and after the First World War, he established good relationships with the German and later British administrators in Iringa and benefited from the war economy.

Mohamed Hamir was a person with strong religious beliefs and community commitment. Towards the of 1929, he expressed to the small Khoja Ismaili Community of Iringa, his desire to build a new Jamatkhana- community center and he personally pledged Shs 40,000/= towards the projected total cost of Shs 60,000 - 65,000. He proposed an ambitious plan to accommodate future settlement in the area, with the new building to seat between 500 to 600 members (the Ismaili population in Iringa at that time, was quite small) and to have primary school as well as sport facilities on the same premises within the compound.

Following the presentation of the proposal to the Ismaili members, Nasser Dossa & Somji Pradhan pledged to donate the land and he personally pledged shs. 40,000 towards the projected total building cost of 60,000 - 65,000 shs. He proposed an ambitious plan to accommodate future settlement in the area, with the new building to seat between 500 to 600 members (the Ismaili population in Iringa at that time was quite small) and to have a primary school as well as sport facilities on the same premises within a compound area.

Because of his previous experience in building work, Mohamedbha had all the design plans ready and he also personally volunteered to be its supervisor, choosing to work with two Hindu "mistrys" named Dewji and Nagji. After many political battles with regards to design and funding, other prominent Ismailis finally pledged the rest of the money for the building, to be paid after the sum of Mohamedbha's initial contribution was spent.

The plan was for a beautiful three-level building with a ground floor and two upper stories halls. The first story to be the main prayer-hall and the second floor to be for a meditation hall baitulkhayal for the intense prayer group. The design was based on the Jamatkhana in Bhuj, in his native Kutch.

After completion of the first floor, Mohamedbha's funds were used up and when he requested the others for their pledged contributions, for various reasons, they were not able to fulfill their commitments. So he had to modify the building plans, deleting the third floor and also having to complete the whole project on his own. He was forced to borrow money from other families he knew outside Iringa who had also come from Kutch.

As per my mother and his daughter, Rehmat Fazal Manji (nee Hamir), and information from my cousin, Diamond Akber Mohamed Hamir (his grandson) and Sikinabai Kanji Lalji, the families who helped him at this time were Kanji Lalji of Mbeya (my father, Fazal Manji Lalji’s uncle) and Dhalla Bhimji of Dar es Salaam.

He also requested a Hindu merchant to supply the building cement on credit with a verbal promise to pay him whenever he could. He pledged to this merchant by "submitting" his pagri (headgear) to the merchant - an Indian custom when one has to borrow money on their "word" and without collateral. For this good cause,the merchant promised to supply as much building materials as needed on credit and respectfully requested Mohamedbha to take back his “pagri”.

In Dar es Salaam, the Darkhana Jamatkhana was also being built around the same time and it too had plans to install a clock tower. Mohamedbha had placed an order for the clock at the same time as the Dar es Salaam order, as they were similar clocks and were being bought from a London company. It so happened that the clock for Dar es Salaam was delayed in manufacturing but the Iringa clock had arrived. Since the Dar es Salaam was scheduled to be opened earlier then Iringa, so following a request from the Dar es Salaam building committee, Mohamedbha generously offered his clock and thus it was installed for the Dar es Salaam Jamatkhana to be ready for the opening ceremony in the early 1930’s. It took about another 6 months for the Iringa clock to arrive

TAAN,MAAN,DHAN - A CASE OF TOTAL CHARITY

With his a masonry experience and to save labour cost, Mohamedbha did the masonry work himself (as seen in the front part of the building in the photos above and the photo on the right) .

His home and duka was next door to Jamatkhana construction site and he used to do work there with the help of his wife, Bachibai after evening prayers and dinner until late in the night. The lighting was provided by kerosene lanterns.

In 1933, with help of Bachibai, the help of Khoja Ismaili families who lent him the extra money and that his Hindu merchant supplier, Mohamed Hamir was able to finish the iconic building, including a large clock tower, at a total cost of Shs 63,000 plus (which equals to approximately US $250,00 in current value), a princely sum during The Great Depression !

Mohamedbha not only paid all the lenders and merchants fully in following few years but he also added another Shs 9,000 donation towards the building of the school to provide access to education to the children of the community as there was no government or community school at that time and so a primary school was established on the ground floor of the building.

UNCONDITIONAL DONATION AND REWARD

In 1933, on behalf of the Hamir family, he unconditionally gifted the Iringa Jamatkhana to the Ismaili Imam of the time, Aga Khan lll. The Imam bestowed him with title of Alijah, granted him an audience and formally accepted the gift during his Golden Jubilee celebrations in Dar es Salaam in 1936.

A TIMELESS LEGACY

Mohamed Hamir was a bold, forward-thinking and dedicated gentleman. He also had the fore-sight to build a Jamatkhana larger than needed at that time. Some 25 years later, the building was modified to accommodate a larger jamaat of Iringa (community had grown five-folds) and it was his only son, Alijah Akber Mohamed Hamir who assisted in the expansion project.

Alijah Mohamed Hamir, who passed away in 1943 and was buried in Iringa, left us an iconic Kutchi landmark in a small town in Tanganyika, a clock for all the town-people to keep time, a a school, community centre and meditation hall for his jamaat to benefit, a beautiful architectural structure for the country and one of the more beautiful jamatkhanas in the world - a very proud legacy for the entire Hamir family and a humbling experience for his grandson to write about it.

https://myemail.constantcontact.com/-De ... 3l-960KlYE

40-storey social housing tower slated for Richards and Drake

A 40-storey social housing tower with cultural spaces for the Ismaili community is slated for the corner of Richards and Drake streets.

The property is currently a two-storey commercial building that’s home to an Ismaili community center and jamatkhana.

The new development will replace the existing community centre and jamatkhana (place of worship), providing 32,300 square feet of new worship, social and educational space in the podium, and 198 social housing units in the tower above.

The unique, triangular design of the tower by DA Architects and Planners is due to the view cone that cuts across the site.

Site plan and photos at:

https://www.urbanyvr.com/richards-and-drake/

A 40-storey social housing tower with cultural spaces for the Ismaili community is slated for the corner of Richards and Drake streets.

The property is currently a two-storey commercial building that’s home to an Ismaili community center and jamatkhana.

The new development will replace the existing community centre and jamatkhana (place of worship), providing 32,300 square feet of new worship, social and educational space in the podium, and 198 social housing units in the tower above.

The unique, triangular design of the tower by DA Architects and Planners is due to the view cone that cuts across the site.

Site plan and photos at:

https://www.urbanyvr.com/richards-and-drake/

Yes multi-generational housing like in Calgary except this is a high-rise building. A project from the Lalji Mangalji family of Vancouver.kmaherali wrote:40-storey social housing tower slated for Richards and Drake

A 40-storey social housing tower with cultural spaces for the Ismaili community is slated for the corner of Richards and Drake streets.

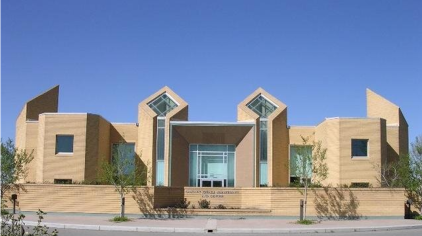

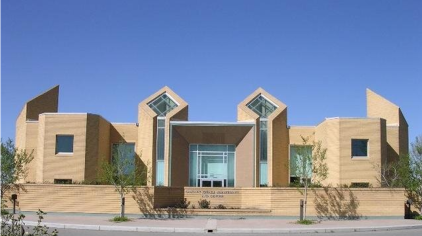

Spring Jamatkhana, Texas

Situated in Spring, a Houston suburb, this Jamatkhana has architectural elements that are reflective of the values and vision of traditional Islamic architecture, such as symmetry, balance, light, and geometry.

The 26,000 sq.ft building sits on 7.74 acres of land and its design was inspired by and conceived with reference to the local Texas environment and the varied backgrounds of the Ismaili community, our history, and expressions of our faith. This Jamatkhana is meant to provide a physical context to inspire future generations while celebrating our faith, history, and the community where the building is situated.

Design Features

Light is one of the primary elements that is used to explore, decorate, and define spaces. In fact, the lighting inside the main building is designed to be indirect, to eliminate glare and reduce the harshness of exposed bulbs and fixtures to all who enter, especially for prayer.

Additionally, design elements include purposeful use of durable materials to ensure longevity, as well as concern for the environment, by being energy efficient, low maintenance, and built for high-traffic usage while encouraging a sense of community.

The original undeveloped site was densely wooded with many species of hardwood trees, such as hickory, oak, holly, and elm, to name a few, as well as softwood trees like gum, pine, tallow, and others. There was also a rich variety of shrubs and undergrowth plants. The goal was to save and maintain as much of the wooded areas as possible.

Inspired by the idea to “build amongst the forest,” the landscape plan consists of maintaining large areas of native green spaces where the existing trees, shrubs, and undergrowth are protected and replenished from areas that were cleared. This was all done in order to maintain the natural environment.

Surrounding the building are large areas of protected and replenished forest that screen parking areas and provide a landscaped tunnel approach towards the two courtyards. Trees and plants were added to provide a start-up landscaped look to areas that were disturbed during construction while the reforestation takes place. New plantings will shape the edge of the forest along with the building that will minimize maintenance and biowaste. The newly planted greenery, landscape tunnel, and canopy screen will take five to ten years to grow and fill in.

The front courtyard and the surrounding area has hard and soft-surface spaces and a water fountain. It was designed as a gathering space, inviting social interaction, and providing an environment for celebrations. This space and nearby covered space in front of the main entrance are a feature in this region referred to as the Mission Style, originally brought from Spain, which was inspired from buildings used by Muslims there and in North Africa.

The main lobby

The main lobby is the hub for community interactions. It provides access to the different wings of the building, the prayer hall and social area, and educational areas, including the Early Childhood Development Center and Library.

The marble and light lenses in the niches, which are handmade, were both sourced from Turkey. Several of the tile areas are sourced locally, and some of the hallway tiles are from Italy.

Decorative elements

Diverse samples selected from various backgrounds and expressions throughout the Islamic world were reinterpreted to provide continuity and to inspire modern creative forms for future generations. For example, the decorative geometric patterns were inspired by a common square-based pattern that has been used historically in Muslim architecture. This element is used throughout the building and is also its motif.

Additionally, the theme of five resonates throughout the building, representing the Panjtan Pak, the five key members of the Prophet Muhammad’s (pbuh) family through Hazrat Ali, i.e. Prophet Muhammad, Hazrat Ali, Fatima, Hasan, and Imam Husayn. An example of this is the five light poles near the parking lot, and five windows in the sitting areas in the main lobby of the prayer hall building.

The design of the building also takes into consideration several aspects of historic Islamic architecture and uses modern processes and materials to create similar effects:

In historic architecture metal-etched and perforated vessels and covers were utilized for holding light sources, such as candles and oil lamps. Here, modern processes were used to cut metal rendered in white for central perforated decorative light covers

Similarly, historically, wood panels with carved patterns for decoration were used. Today, similar wood panels are used but with modern processes to cut patterns into the panels

Structural sunscreens used in historical architecture are visible here through the sunscreen shading for the aluminum and glass curtain wall

Carved plaster walls and ceiling patterns are represented in the niches and decorative cut ceiling tile in the Prayer Hall

Decorative screens are represented in the ceiling screens, HVAC grilles, and skylights

Plaster and masonry walls with light niches have been converted into wood niches and wood-paneled walls were created to illuminate seating areas

Additionally, there are a number of environmentally-conscious features within the building:

To reduce heat and energy use, the construction includes:

Additional insulation

A white colored roof and building

Large canopy overhangs

Curtain walls, windows and skylights with insulated glass and thermal-break aluminum frames

Decorative metal screens to shade the curtain wall

The facility uses natural lighting for a majority of daytime use, however, when needed, the building utilizes energy-efficient technology including an energy efficient HVAC system and LED lighting

Construction of the building includes locally-sourced materials, along with recyclable content to minimize landfills and the building’s carbon footprint

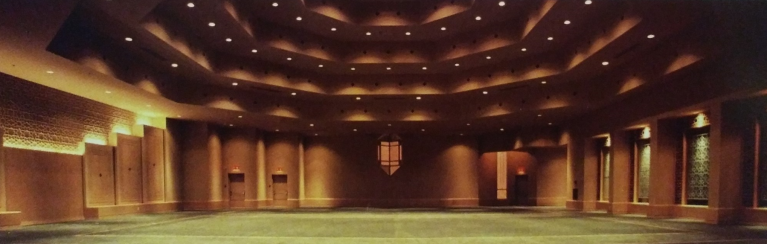

The Prayer Hall

Specific effort was made to remove any bright spots and have light fade as it gets closer to the spatial area where an individual prays. The prayer hall carpet is inspired by rainbow colors, furthering the theme of light in its prismatic form.

There are carved plaster walls, ceiling patterns, and complex geometric shapes and patterns that are common in Islamic architecture. They also convey a feeling of spaciousness, calmness, openness, and tranquility.

Social Hall

There is an intricate design on the ceiling. The rotated square inside itself is common in the Pamirs (Tajikistan). The rotated square on top of itself is common in the Northern Subcontinent, Persia, Turkey, North Africa, and Southeast Asia. The combination of these patterns was inspired from Syria and the Middle East. The screen above the skylight is influenced from Mughal architecture and the light fixture is inspired by lighting influences from the Swahili coast.

A water feature in the Contemplation Courtyard

Contemplation Courtyard

This area offers spaces creating a serene environment surrounded by lush greenery and a water element. Additional environmentally-friendly features of the site include:

- Saving part of the forest and reforestation by planting about 4,500 trees and plants for carbon capture. This is more than what was removed from the site in order to build the structure.

- Collecting rain on some parts of concrete pavement and directing it to replenish underground water flow to support existing forest, landscaping, and reforestation

- Collecting rainwater from the main building roof into two 5,000 gallon cisterns for irrigating landscaped areas

- Capability to store an additional 20,000 gallons of rain from the side building and drop off canopy roof for additional irrigating capacity

- Using tree canopy to shade the building from the sun

- Landscaping design that uses less potable water and does not need to be cut and trimmed regularly

photos at:

https://the.ismaili/usa/spring-jamatkhana-texas

Situated in Spring, a Houston suburb, this Jamatkhana has architectural elements that are reflective of the values and vision of traditional Islamic architecture, such as symmetry, balance, light, and geometry.

The 26,000 sq.ft building sits on 7.74 acres of land and its design was inspired by and conceived with reference to the local Texas environment and the varied backgrounds of the Ismaili community, our history, and expressions of our faith. This Jamatkhana is meant to provide a physical context to inspire future generations while celebrating our faith, history, and the community where the building is situated.

Design Features

Light is one of the primary elements that is used to explore, decorate, and define spaces. In fact, the lighting inside the main building is designed to be indirect, to eliminate glare and reduce the harshness of exposed bulbs and fixtures to all who enter, especially for prayer.

Additionally, design elements include purposeful use of durable materials to ensure longevity, as well as concern for the environment, by being energy efficient, low maintenance, and built for high-traffic usage while encouraging a sense of community.

The original undeveloped site was densely wooded with many species of hardwood trees, such as hickory, oak, holly, and elm, to name a few, as well as softwood trees like gum, pine, tallow, and others. There was also a rich variety of shrubs and undergrowth plants. The goal was to save and maintain as much of the wooded areas as possible.

Inspired by the idea to “build amongst the forest,” the landscape plan consists of maintaining large areas of native green spaces where the existing trees, shrubs, and undergrowth are protected and replenished from areas that were cleared. This was all done in order to maintain the natural environment.

Surrounding the building are large areas of protected and replenished forest that screen parking areas and provide a landscaped tunnel approach towards the two courtyards. Trees and plants were added to provide a start-up landscaped look to areas that were disturbed during construction while the reforestation takes place. New plantings will shape the edge of the forest along with the building that will minimize maintenance and biowaste. The newly planted greenery, landscape tunnel, and canopy screen will take five to ten years to grow and fill in.

The front courtyard and the surrounding area has hard and soft-surface spaces and a water fountain. It was designed as a gathering space, inviting social interaction, and providing an environment for celebrations. This space and nearby covered space in front of the main entrance are a feature in this region referred to as the Mission Style, originally brought from Spain, which was inspired from buildings used by Muslims there and in North Africa.

The main lobby

The main lobby is the hub for community interactions. It provides access to the different wings of the building, the prayer hall and social area, and educational areas, including the Early Childhood Development Center and Library.

The marble and light lenses in the niches, which are handmade, were both sourced from Turkey. Several of the tile areas are sourced locally, and some of the hallway tiles are from Italy.

Decorative elements

Diverse samples selected from various backgrounds and expressions throughout the Islamic world were reinterpreted to provide continuity and to inspire modern creative forms for future generations. For example, the decorative geometric patterns were inspired by a common square-based pattern that has been used historically in Muslim architecture. This element is used throughout the building and is also its motif.

Additionally, the theme of five resonates throughout the building, representing the Panjtan Pak, the five key members of the Prophet Muhammad’s (pbuh) family through Hazrat Ali, i.e. Prophet Muhammad, Hazrat Ali, Fatima, Hasan, and Imam Husayn. An example of this is the five light poles near the parking lot, and five windows in the sitting areas in the main lobby of the prayer hall building.

The design of the building also takes into consideration several aspects of historic Islamic architecture and uses modern processes and materials to create similar effects:

In historic architecture metal-etched and perforated vessels and covers were utilized for holding light sources, such as candles and oil lamps. Here, modern processes were used to cut metal rendered in white for central perforated decorative light covers

Similarly, historically, wood panels with carved patterns for decoration were used. Today, similar wood panels are used but with modern processes to cut patterns into the panels

Structural sunscreens used in historical architecture are visible here through the sunscreen shading for the aluminum and glass curtain wall

Carved plaster walls and ceiling patterns are represented in the niches and decorative cut ceiling tile in the Prayer Hall

Decorative screens are represented in the ceiling screens, HVAC grilles, and skylights

Plaster and masonry walls with light niches have been converted into wood niches and wood-paneled walls were created to illuminate seating areas

Additionally, there are a number of environmentally-conscious features within the building:

To reduce heat and energy use, the construction includes:

Additional insulation

A white colored roof and building

Large canopy overhangs

Curtain walls, windows and skylights with insulated glass and thermal-break aluminum frames

Decorative metal screens to shade the curtain wall

The facility uses natural lighting for a majority of daytime use, however, when needed, the building utilizes energy-efficient technology including an energy efficient HVAC system and LED lighting

Construction of the building includes locally-sourced materials, along with recyclable content to minimize landfills and the building’s carbon footprint

The Prayer Hall

Specific effort was made to remove any bright spots and have light fade as it gets closer to the spatial area where an individual prays. The prayer hall carpet is inspired by rainbow colors, furthering the theme of light in its prismatic form.

There are carved plaster walls, ceiling patterns, and complex geometric shapes and patterns that are common in Islamic architecture. They also convey a feeling of spaciousness, calmness, openness, and tranquility.

Social Hall

There is an intricate design on the ceiling. The rotated square inside itself is common in the Pamirs (Tajikistan). The rotated square on top of itself is common in the Northern Subcontinent, Persia, Turkey, North Africa, and Southeast Asia. The combination of these patterns was inspired from Syria and the Middle East. The screen above the skylight is influenced from Mughal architecture and the light fixture is inspired by lighting influences from the Swahili coast.

A water feature in the Contemplation Courtyard

Contemplation Courtyard

This area offers spaces creating a serene environment surrounded by lush greenery and a water element. Additional environmentally-friendly features of the site include:

- Saving part of the forest and reforestation by planting about 4,500 trees and plants for carbon capture. This is more than what was removed from the site in order to build the structure.

- Collecting rain on some parts of concrete pavement and directing it to replenish underground water flow to support existing forest, landscaping, and reforestation

- Collecting rainwater from the main building roof into two 5,000 gallon cisterns for irrigating landscaped areas

- Capability to store an additional 20,000 gallons of rain from the side building and drop off canopy roof for additional irrigating capacity

- Using tree canopy to shade the building from the sun

- Landscaping design that uses less potable water and does not need to be cut and trimmed regularly

photos at:

https://the.ismaili/usa/spring-jamatkhana-texas

39-storey tower with 100% social housing approved for downtown Vancouver

Last week during a public hearing, Vancouver City Council approved one of its largest standalone social housing projects to date — a 411-ft-tall, 39-storey tower with 193 units https://dailyhive.com/vancouver/508-dra ... ity-centre.

City council approved the project unanimously, with independent councillor Colleen Hardwick abstaining from the decision.

The project is spearheaded by MCYH Multigenerational Housing Society in partnership with Larco, and DA Architects and Planners is the design firm.

Since the rezoning application was submitted in Fall 2020, the total number of social housing units has been slightly reduced from 198 to 193, but this was done to achieve larger and more functional units within a challenging triangular-shaped floor plate, similar to the Living Shangri-La tower.

The lower floors of the tower are rectangular in shaped, but the upper floors starting from the 10th floor are roughly half the size of the base floors to avoid intruding into view cones B1 and C1 protecting the view of The Lions’ mountains from the South False Creek seawall at Charleson Park and the Laurel Street Landbridge Park near West 7th Avenue.

The tower’s height also maximizes on its allowable height, restricted by View Cone 3 emanating from Queen Elizabeth Park.

The view cones were a point of contention for one public speaker during the public hearing, who criticized the municipal planners and pleaded to city council to consider view cone relaxations for social housing projects in the future.

Upper floor plates that followed the larger size of the floor plates in the base of the building would conceivably generate more social housing units, improve the livability of the units through more efficient unit layouts, and improve the financial outlook of the project. As a result of the limitations, there are generally just five units per floor.

More images and details at:

https://dailyhive.com/vancouver/508-dra ... al-housing

Last week during a public hearing, Vancouver City Council approved one of its largest standalone social housing projects to date — a 411-ft-tall, 39-storey tower with 193 units https://dailyhive.com/vancouver/508-dra ... ity-centre.

City council approved the project unanimously, with independent councillor Colleen Hardwick abstaining from the decision.

The project is spearheaded by MCYH Multigenerational Housing Society in partnership with Larco, and DA Architects and Planners is the design firm.

Since the rezoning application was submitted in Fall 2020, the total number of social housing units has been slightly reduced from 198 to 193, but this was done to achieve larger and more functional units within a challenging triangular-shaped floor plate, similar to the Living Shangri-La tower.

The lower floors of the tower are rectangular in shaped, but the upper floors starting from the 10th floor are roughly half the size of the base floors to avoid intruding into view cones B1 and C1 protecting the view of The Lions’ mountains from the South False Creek seawall at Charleson Park and the Laurel Street Landbridge Park near West 7th Avenue.

The tower’s height also maximizes on its allowable height, restricted by View Cone 3 emanating from Queen Elizabeth Park.

The view cones were a point of contention for one public speaker during the public hearing, who criticized the municipal planners and pleaded to city council to consider view cone relaxations for social housing projects in the future.

Upper floor plates that followed the larger size of the floor plates in the base of the building would conceivably generate more social housing units, improve the livability of the units through more efficient unit layouts, and improve the financial outlook of the project. As a result of the limitations, there are generally just five units per floor.

More images and details at:

https://dailyhive.com/vancouver/508-dra ... al-housing

FRI Aug 13 • 5:30pm PT | 8:30pm ET • Live Stream

Summer Reflections: Of Order, Of Peace, Of Prayer

This evening on Summer Reflections, we take a journey into the Ismaili Centre, Vancouver, where we will explore the space through the lens of the architect Bruno Freschi.

Through a virtual tour, and in conversation with CBC's Zahra Premji, Mr. Freschi will share his personal insights on how he brought to life Mawlana Hazar Imam's vision for the Centre, and what truly inspired him when he was designing this magnificent space. From the smallest details to the grandest idea, join us for a glimpse into the creative process that led to the design of the Ismaili Centre, Vancouver.

Join us at iiCanada.live.

Daily Diamond

"The new building will stand in strongly landscaped surroundings. It will face a courtyard with foundations and a garden. Its scale, its proportions and the use of water will serve to create a serene and contemplative environment. This will be a place of congregation, of order, of peace, of prayer, of hope, of humility, and of brotherhood. From it should come forth those thoughts, those sentiments, those attitudes, which bind men together and which unite. It has been conceived and will exist in a mood of friendship, courtesy, and harmony."

Mawlana Hazar Imam, Burnaby, July 1982

Summer Reflections: Of Order, Of Peace, Of Prayer

This evening on Summer Reflections, we take a journey into the Ismaili Centre, Vancouver, where we will explore the space through the lens of the architect Bruno Freschi.

Through a virtual tour, and in conversation with CBC's Zahra Premji, Mr. Freschi will share his personal insights on how he brought to life Mawlana Hazar Imam's vision for the Centre, and what truly inspired him when he was designing this magnificent space. From the smallest details to the grandest idea, join us for a glimpse into the creative process that led to the design of the Ismaili Centre, Vancouver.

Join us at iiCanada.live.

Daily Diamond

"The new building will stand in strongly landscaped surroundings. It will face a courtyard with foundations and a garden. Its scale, its proportions and the use of water will serve to create a serene and contemplative environment. This will be a place of congregation, of order, of peace, of prayer, of hope, of humility, and of brotherhood. From it should come forth those thoughts, those sentiments, those attitudes, which bind men together and which unite. It has been conceived and will exist in a mood of friendship, courtesy, and harmony."

Mawlana Hazar Imam, Burnaby, July 1982

Ground Breaking of Four Jamatkhanas in Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral

The ongoing development of new Jamatkhanas in the northern areas of Pakistan has constituted the ground breaking of four new Jamatkhanas in Gilgit-Baltistan and Upper Chitral. The new spaces allocated are seismic-resistant and will serve as a multipurpose space for the community.

Built on high altitudes, the Jamatkhanas will be constructed in collaboration with local communities who are assisting in the transportation of local material, stones and other necessary items used in construction. To address the harsh winter and other challenges posed by the natural environment, the Jamatkhanas will be fully insulated with heaters.

AlKarim Jamatkhana in the Ishkoman Puniyal region will be the largest of the four. It will meet the needs of the Jamat in many ways. Besides the prayer hall and two educational halls, the Jamatkhana will also have a multipurpose hall which will be used for developing the capacity of the local community.

Dado Khan, President, Ismaili Council for Ishkoman Puniyal, explained that “There are many unique features in the newly constructed Jamatkhanas. Particularly in the AlKarim Jamatkhana, benches are being constructed that will help with social inclusion, a walking track for healthy activities as well as a ramp for senior citizens and the physically-disabled members of the Jamat. Similarly, in the playgroup rooms, a multipurpose area is being developed that will be conducive in promoting learning activities amongst ECD groups as well as developing leadership skills of the Jamat.” -

The second Jamatkhana in Himachal Village, Ishkoman Puniyal region will have a prayer hall and two rooms for community engagements. The other two Jamatkhanas, one located in Khuz Darmiyan of Upper Chitral and the other in Gareth of Hunza, will have a prayer hall and two rooms for Jamati engagements.

“The construction of a new state-of-the-art Jamatkhana at Gareth, with the allied facilities of REC, offices and an open prayer hall, right in the heart of Central Hunza, will definitely be an addition to the quality construction of Imamati structures. It is hoped that the Jamat will materially and spiritually benefit from the environment created by the new Jamatkhana at Gareth.”

Experts at the Aga Khan Agency for Habitat (AKAH) conducted Hazard Vulnerability Risk Assessments at all sites in order to ensure safe zones for Jamatkhana construction. The Jamatkhana structures have used flexible, Building and Construction Improvement Programme (BACIP) galvanised wire which adjusts to the contours of uneven stone masonry, thus providing seismic resistance.

Imtiaz Alam, President, Ismaili Council for Upper Chitral highlighted that “The new Jamatkhana in Khuz Darmiyan is the first of its kind and an example for the community and other Jamatkhanas to be constructed. The material that will be used in the construction is unique and reflects the local culture.”

The new Jamatkhanas will not only create a space for the Jamat to gather for prayer, learning and social functions, they will also act as shelters in the event of a natural disaster. Through sharing of best practices, these spaces will also encourage the Jamat and neighbouring communities to adopt similar construction practices in their own buildings.

Photos at:

https://the.ismaili/pakistan/our-commun ... nd-chitral

The ongoing development of new Jamatkhanas in the northern areas of Pakistan has constituted the ground breaking of four new Jamatkhanas in Gilgit-Baltistan and Upper Chitral. The new spaces allocated are seismic-resistant and will serve as a multipurpose space for the community.

Built on high altitudes, the Jamatkhanas will be constructed in collaboration with local communities who are assisting in the transportation of local material, stones and other necessary items used in construction. To address the harsh winter and other challenges posed by the natural environment, the Jamatkhanas will be fully insulated with heaters.

AlKarim Jamatkhana in the Ishkoman Puniyal region will be the largest of the four. It will meet the needs of the Jamat in many ways. Besides the prayer hall and two educational halls, the Jamatkhana will also have a multipurpose hall which will be used for developing the capacity of the local community.

Dado Khan, President, Ismaili Council for Ishkoman Puniyal, explained that “There are many unique features in the newly constructed Jamatkhanas. Particularly in the AlKarim Jamatkhana, benches are being constructed that will help with social inclusion, a walking track for healthy activities as well as a ramp for senior citizens and the physically-disabled members of the Jamat. Similarly, in the playgroup rooms, a multipurpose area is being developed that will be conducive in promoting learning activities amongst ECD groups as well as developing leadership skills of the Jamat.” -

The second Jamatkhana in Himachal Village, Ishkoman Puniyal region will have a prayer hall and two rooms for community engagements. The other two Jamatkhanas, one located in Khuz Darmiyan of Upper Chitral and the other in Gareth of Hunza, will have a prayer hall and two rooms for Jamati engagements.

“The construction of a new state-of-the-art Jamatkhana at Gareth, with the allied facilities of REC, offices and an open prayer hall, right in the heart of Central Hunza, will definitely be an addition to the quality construction of Imamati structures. It is hoped that the Jamat will materially and spiritually benefit from the environment created by the new Jamatkhana at Gareth.”

Experts at the Aga Khan Agency for Habitat (AKAH) conducted Hazard Vulnerability Risk Assessments at all sites in order to ensure safe zones for Jamatkhana construction. The Jamatkhana structures have used flexible, Building and Construction Improvement Programme (BACIP) galvanised wire which adjusts to the contours of uneven stone masonry, thus providing seismic resistance.

Imtiaz Alam, President, Ismaili Council for Upper Chitral highlighted that “The new Jamatkhana in Khuz Darmiyan is the first of its kind and an example for the community and other Jamatkhanas to be constructed. The material that will be used in the construction is unique and reflects the local culture.”

The new Jamatkhanas will not only create a space for the Jamat to gather for prayer, learning and social functions, they will also act as shelters in the event of a natural disaster. Through sharing of best practices, these spaces will also encourage the Jamat and neighbouring communities to adopt similar construction practices in their own buildings.

Photos at:

https://the.ismaili/pakistan/our-commun ... nd-chitral

Redevelopment of Don Mills Jamatkhane: IMARA National Feroz Ashraf has submitted to the City of Toronto Site Plan Application to permit the redevelopment of Don Mills Jamatkhane: 4 storey multipurpose facility, consisting of a Ismaili Community Centre, Jamatkhana (place of worship) with offices, meetings rooms, including 2 levels of proposed underground parking. See attached PDF Architectural Plans.

For further updates please visit

https://urbantoronto.ca/forum/threads/t ... 94a.32372/

Nairobi’s iconic Town Jamatkhana celebrates 100 years

On the historic evening of 14 January 1922, as daylight turned to dusk, prayers were recited at the Nairobi Town Jamatkhana for the very first time.

Large crowds gathered outside the vast stone structure — the tallest building in Nairobi at the time — with its wood-framed windows and soaring columns, to witness the moment its large doors first swung open to the Jamat.

Situated at the junction of Moi Avenue and River Road, the building’s lofty clock-tower, visible from many streets away, became a new landmark for residents and tradespeople in the growing township, and symbolised the permanent settlement of the Jamat in Kenya.

A full century has now passed since that momentous day. Over this time, the building has contributed to the lasting legacy established by the Ismaili community and its institutions in Kenya’s capital and beyond.

An edifice of history

For Ismailis who grew up in Nairobi, the famous building evokes fond memories. Some still live in the city, while others have moved on to other parts of the world. For all of them, Town Jamatkhana was the starting point as they began their lives in Kenya.

“For any Ismaili who arrived with their bags at Nairobi railway station, their first port of call was Town Jamatkhana,” said Mehboob Habib, who grew up in Nairobi and is now based in Toronto, Canada.

“Even if you didn’t know anyone in Nairobi, it was a place where you could go and know that you would receive some sort of assistance. Someone would take care of you.”

Local residents dubbed the building “Khoja Mosque,” referring to the Ismailis of Indian origin who settled in Kenya in the early 20th century. It still goes by this name in tourist maps and city guidebooks, and was listed in 2001 as one of the country’s heritage monuments.

The Jamatkhana also spurred the growth of businesses in its immediate vicinity. Shops, restaurants, and cafés sprung up on the adjacent road, named ‘Bazaar Street’ at the time for its marketplace atmosphere. It was later renamed Biashara Street, after the Swahili word for commerce or trade.

It became a sparkling feature of the city in more ways than one, especially when lit up on commemorative days, becoming a majestic ‘palace in the sky.’

“On every special occasion; a jubilee, a festival, independence celebrations, or when the Imam visited; the Jamatkhana would be decorated in spectacular lights, and the Aga Khan Band would play,” Mehboob continued.

“People would travel from far and wide — Ismailis and others — just to see the splendour of the lights and hear the band. There was nothing like it.”

For those who were there to witness these moments, and others who lived these through their stories, the Town Jamatkhana has an extra special place in their hearts, for it was here in 1944, that Mawlana Hazar Imam recited the namaz during Eid ul-Fitr ceremonies, at the age of eight.

A multi-function space

It was a remarkable feat of engineering for its time, taking only two years from laying the foundation stone to completing construction. Today, the three-storey Victorian-style building, designed by Virji Nanji Khambhaita, retains much of its original detail.

“The foyer of the building features magnificent arches and moulded ceilings, while an atrium in its centre floods the space with natural light,” described Dr Azim Lakhani, AKDN Diplomatic Representative to Kenya.

“Balustrades are finished in beautifully handcrafted timber. Panelled timber doors sit in arched timber frames and many floors are finished in patterned terrazzo.”

“In time, the landmark building supported the religious and social aspects of the Ismaili Community’s lives,” Dr Lakhani added, “comprising prayer halls, as well as spaces for social events, learning, and administrative offices.”

Soundproof windows on the upper floors absorb the buzz and bustle of the city below, and allow for a serene environment for prayer and meditation.

“The Jamatkhana had a large library stocked with secular and religious books for the Jamat to read there and borrow - a rarity at the time,” said D’jemilla Daya, who was raised in Nairobi and now lives in the UK.

“Many people used to go there in the morning before work to read the newspapers, and children would gather there after prayers to browse the comics.”

As with Jamatkhanas in other parts of the world, this one has evolved in form and function over time, reflecting the changing local context and needs of the community.

In recent years, the building’s spaces have been used for public exhibitions and events, including Rays of Light; Prince Hussain’s Fragile Beauty exhibition; Ismailis in Kenya: a Photographic Journey; and a workshop on the environment chaired by Prince Rahim.

Members of the Jamat also mark important rites of passage here, such as birth, marriage, and death. All events and programmes are organised by volunteers who wish to serve the community and wider society.

“I was fortunate to be married at Town Jamatkhana in 1985, and now I have the opportunity to officiate weddings here,” said Moez Manji, who currently serves as Mukhi Saheb.

“As the present office bearers, we strive to continue a long tradition of service, embodied by the many Mukhi Kamadias and volunteers who have come before us.”

A century of memories

Throughout 2022, the Jamat will celebrate the Centenary year of Nairobi’s Town Jamatkhana, and its historical significance for the Jamat and the country as a whole.

Over the years, Ismailis who attended as children have gone on to make important contributions to business, academia, and civil society in Kenya and around the world, as have their children and grandchildren in turn.

“I’ve heard so many stories centred around Town Jamatkhana, and there must be many more I haven’t heard,” said Nabila Walji, from Edmonton, Canada.

Nabila’s great grandfather opened and managed the popular Ismailia Hotel restaurant across the street, witnessing the comings and goings of people and the steady development of the local area over time.

“When I would visit, I felt a sense of continuity with generations of the past. The legacy of our ancestors in the city is evident in this much-loved building.”

With the rise of ever taller structures and busy streets in the heart of Nairobi, the Jamatkhana’s clock tower continues to represent stability through changing times. Today the building remains a place of peace and solace, offering precious memories for all who walk through its timber doors.

“For a century now, our treasured Town Jamatkhana has symbolised the Ismaili community’s permanent presence in Kenya, along with our contributions to the country’s progress - through the work of our institutions, volunteers, and outreach partners,” said Shamira Dostmohamed, President of the Ismaili Council for Kenya.

“We look forward to working together on plans for the next 100 years.”

Photos at:

https://the.ismaili/global/news/communi ... -100-years

On the historic evening of 14 January 1922, as daylight turned to dusk, prayers were recited at the Nairobi Town Jamatkhana for the very first time.

Large crowds gathered outside the vast stone structure — the tallest building in Nairobi at the time — with its wood-framed windows and soaring columns, to witness the moment its large doors first swung open to the Jamat.

Situated at the junction of Moi Avenue and River Road, the building’s lofty clock-tower, visible from many streets away, became a new landmark for residents and tradespeople in the growing township, and symbolised the permanent settlement of the Jamat in Kenya.

A full century has now passed since that momentous day. Over this time, the building has contributed to the lasting legacy established by the Ismaili community and its institutions in Kenya’s capital and beyond.

An edifice of history

For Ismailis who grew up in Nairobi, the famous building evokes fond memories. Some still live in the city, while others have moved on to other parts of the world. For all of them, Town Jamatkhana was the starting point as they began their lives in Kenya.

“For any Ismaili who arrived with their bags at Nairobi railway station, their first port of call was Town Jamatkhana,” said Mehboob Habib, who grew up in Nairobi and is now based in Toronto, Canada.

“Even if you didn’t know anyone in Nairobi, it was a place where you could go and know that you would receive some sort of assistance. Someone would take care of you.”

Local residents dubbed the building “Khoja Mosque,” referring to the Ismailis of Indian origin who settled in Kenya in the early 20th century. It still goes by this name in tourist maps and city guidebooks, and was listed in 2001 as one of the country’s heritage monuments.

The Jamatkhana also spurred the growth of businesses in its immediate vicinity. Shops, restaurants, and cafés sprung up on the adjacent road, named ‘Bazaar Street’ at the time for its marketplace atmosphere. It was later renamed Biashara Street, after the Swahili word for commerce or trade.

It became a sparkling feature of the city in more ways than one, especially when lit up on commemorative days, becoming a majestic ‘palace in the sky.’

“On every special occasion; a jubilee, a festival, independence celebrations, or when the Imam visited; the Jamatkhana would be decorated in spectacular lights, and the Aga Khan Band would play,” Mehboob continued.

“People would travel from far and wide — Ismailis and others — just to see the splendour of the lights and hear the band. There was nothing like it.”

For those who were there to witness these moments, and others who lived these through their stories, the Town Jamatkhana has an extra special place in their hearts, for it was here in 1944, that Mawlana Hazar Imam recited the namaz during Eid ul-Fitr ceremonies, at the age of eight.

A multi-function space

It was a remarkable feat of engineering for its time, taking only two years from laying the foundation stone to completing construction. Today, the three-storey Victorian-style building, designed by Virji Nanji Khambhaita, retains much of its original detail.

“The foyer of the building features magnificent arches and moulded ceilings, while an atrium in its centre floods the space with natural light,” described Dr Azim Lakhani, AKDN Diplomatic Representative to Kenya.

“Balustrades are finished in beautifully handcrafted timber. Panelled timber doors sit in arched timber frames and many floors are finished in patterned terrazzo.”

“In time, the landmark building supported the religious and social aspects of the Ismaili Community’s lives,” Dr Lakhani added, “comprising prayer halls, as well as spaces for social events, learning, and administrative offices.”

Soundproof windows on the upper floors absorb the buzz and bustle of the city below, and allow for a serene environment for prayer and meditation.

“The Jamatkhana had a large library stocked with secular and religious books for the Jamat to read there and borrow - a rarity at the time,” said D’jemilla Daya, who was raised in Nairobi and now lives in the UK.

“Many people used to go there in the morning before work to read the newspapers, and children would gather there after prayers to browse the comics.”

As with Jamatkhanas in other parts of the world, this one has evolved in form and function over time, reflecting the changing local context and needs of the community.

In recent years, the building’s spaces have been used for public exhibitions and events, including Rays of Light; Prince Hussain’s Fragile Beauty exhibition; Ismailis in Kenya: a Photographic Journey; and a workshop on the environment chaired by Prince Rahim.

Members of the Jamat also mark important rites of passage here, such as birth, marriage, and death. All events and programmes are organised by volunteers who wish to serve the community and wider society.

“I was fortunate to be married at Town Jamatkhana in 1985, and now I have the opportunity to officiate weddings here,” said Moez Manji, who currently serves as Mukhi Saheb.

“As the present office bearers, we strive to continue a long tradition of service, embodied by the many Mukhi Kamadias and volunteers who have come before us.”

A century of memories

Throughout 2022, the Jamat will celebrate the Centenary year of Nairobi’s Town Jamatkhana, and its historical significance for the Jamat and the country as a whole.

Over the years, Ismailis who attended as children have gone on to make important contributions to business, academia, and civil society in Kenya and around the world, as have their children and grandchildren in turn.

“I’ve heard so many stories centred around Town Jamatkhana, and there must be many more I haven’t heard,” said Nabila Walji, from Edmonton, Canada.

Nabila’s great grandfather opened and managed the popular Ismailia Hotel restaurant across the street, witnessing the comings and goings of people and the steady development of the local area over time.

“When I would visit, I felt a sense of continuity with generations of the past. The legacy of our ancestors in the city is evident in this much-loved building.”

With the rise of ever taller structures and busy streets in the heart of Nairobi, the Jamatkhana’s clock tower continues to represent stability through changing times. Today the building remains a place of peace and solace, offering precious memories for all who walk through its timber doors.

“For a century now, our treasured Town Jamatkhana has symbolised the Ismaili community’s permanent presence in Kenya, along with our contributions to the country’s progress - through the work of our institutions, volunteers, and outreach partners,” said Shamira Dostmohamed, President of the Ismaili Council for Kenya.

“We look forward to working together on plans for the next 100 years.”

Photos at:

https://the.ismaili/global/news/communi ... -100-years

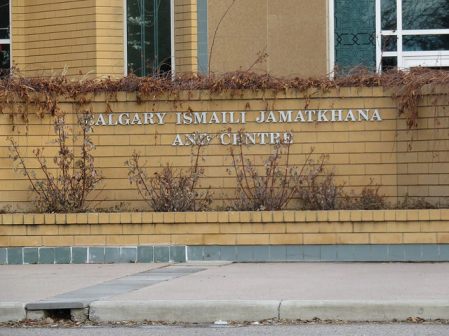

Twenty-fifth anniversary of the Calgary Ismaili Jamatkhana and Centre, Canada

BY NIMIRA DEWJI POSTED ON JANUARY 14, 2022

The Calgary Ismaili Jamatkhana and Centre was officially opened on 15 January 1997, commemorating its twenty-fifth anniversary.

Image: FNDA

Walk Calgary Communities: Calgary Ismaili Jamatkhana and Centre

Image: Flickr

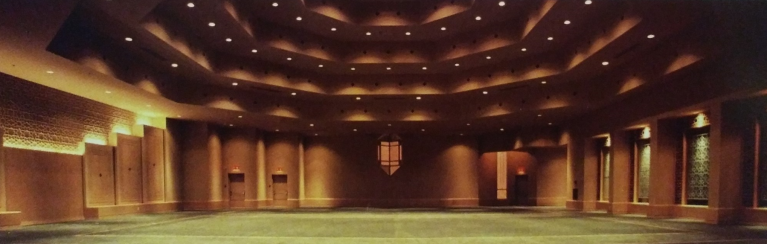

A section of the prayer hall, Ismaili Jamatkhana and Centre Calgary. Image: FNDA

Prayer hall, Ismaili Jamatkhana and Centre, Calgary. Image: Smiley Ismaili

The groundbreaking ceremony of this first purpose built Jamatkhana in Calgary, designed by Farouk Noormohamed, was performed by then Premier of Alberta Ralph Klein and then Mayor Al Duerr, presided by then President of the Council for the Prairies Salim Sumar.

Ralph Klein (left) and Al Duerr perform groundbreaking of Ismaili Jamatkhana and Centre, Calgary as Salim Sumar (far right) and other dignitaries applaud. Image: Smiley Ismaili.

From the Arabic word jama‘a (gathering) and the Persian word khana (house, place), a jamatkhana is a place of gathering for worship as well as social and educational activities for the Nizari and Mustalian Ismailis. The Chisti Sufis, among other communities, also gather in jamatkhanas.

During the time of the Prophet, the community congregated in the masjid, a place of prostration (from the Arabic root sa-ja-da, meaning ‘to prostrate’). In the early Islamic era, the word masjid meant a place of prayer which could be any clean spot on earth. The first masjid, built in Medina in 622 CE, was primarily a designated space for the offering of canonical ritual prayers by Muslim congregations. Besides its religious function, masjid is also used as the centre of community life which can serve social, political and educational roles (IIS).

Over time, as Islam expanded and diverse interpretations arose, a variety of spaces of worship and gathering developed, with architectural styles reflecting the respective local cultures and materials.

Khaniqa/Khaniqah – from Persian, lit. ‘residence,’ the khaniqa is a term for a Sufi meeting house which serves as a residential teaching centre for Sufi disciples. A famous khaniqa was established by Muhammad ibn Karram (d. 839 CE) the founder of the Karramiyya tariqah. Khaniqahha are usually designed to house Sufis, provide places for communal worship, and feed the residents, guests and travellers (IIS).

Ribat – from the Arabic root ra-ba-ta meaning ‘to attach’ or ‘to link’; and for in certain Sufi traditions it means strengthening the heart. Ribat as a building could describe a small fort, a fortified place, or an urban establishment for mystics who gathered there to study, pray, and write. The earliest foundations of this kind of building date back to the first half-century of the ‘Abbasid period (750-1258 CE) (IIS).

Ribat Monastir, Sousse, Tunisia. Image: Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, Brown University

Zawiya – from the Arabic meaning ‘a corner,’ it is a Sufi place of worship referring to the corner of a mosque where a worshiper would isolate to perform dhikr, or may refer to a mausoleum of a saint or the founder of a specific Sufi tariqah. The names of these centres have varied according to location: zawiya and ribat were used mostly in the Maghrib (present-day Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia); khanaqah in Egypt, Syria, and Iran; khanagah from Iran to India (the term dargah is also used); and tekke in Turkish-speaking areas.

At the foundation ceremony of the Ismaili Centre, Dubai on 13 December 2003, His Highness Aga Khan IV reflected upon the co-existence of the diverse spaces of worship:

“For many centuries, a prominent feature of the Muslim religious landscape has been the variety of spaces of gathering co-existing harmoniously with the masjid, which in itself has accommodated a range of diverse institutional spaces for educational, social and reflective purposes. Historically serving communities of different interpretations and spiritual affiliations, these spaces have retained their cultural nomenclatures and characteristics, from ribat and zawiyya to khanaqa and jamatkhana.

The congregational space incorporated within the Ismaili Centre belongs to the historic category of jamatkhana, an institutional category that also serves a number of sister Sunni and Shia communities, in their respective contexts, in many parts of the world. Here, it will be space reserved for traditions and practices specific to the Shia Ismaili Tariqah of Islam.”

Speech

Sources:

Karim Jiwani, Muslim Spaces of Piety and Worship, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Oleg Grabar, “The Mosque,” Islam: Art and Architecture Edited by Markus Hattstein and Peter Delius. Cologne, Konenmann, 2000

~*~*~

Contributed to Ismailimail by Nimira Dewji. Nimira is an invited writer although she has contributed several articles in the past (view previous articles). She also has her own blog – Nimirasblog – where she writes short articles on Ismaili history and Muslim civilisations. When not researching and writing, Nimira volunteers at a shelter for those experiencing homelessness, and at a women’s shelter. She can be reached at [email protected].

https://ismailimail.blog/2022/01/14/twe ... re-canada/

BY NIMIRA DEWJI POSTED ON JANUARY 14, 2022

The Calgary Ismaili Jamatkhana and Centre was officially opened on 15 January 1997, commemorating its twenty-fifth anniversary.

Image: FNDA

Walk Calgary Communities: Calgary Ismaili Jamatkhana and Centre

Image: Flickr

A section of the prayer hall, Ismaili Jamatkhana and Centre Calgary. Image: FNDA

Prayer hall, Ismaili Jamatkhana and Centre, Calgary. Image: Smiley Ismaili

The groundbreaking ceremony of this first purpose built Jamatkhana in Calgary, designed by Farouk Noormohamed, was performed by then Premier of Alberta Ralph Klein and then Mayor Al Duerr, presided by then President of the Council for the Prairies Salim Sumar.

Ralph Klein (left) and Al Duerr perform groundbreaking of Ismaili Jamatkhana and Centre, Calgary as Salim Sumar (far right) and other dignitaries applaud. Image: Smiley Ismaili.

From the Arabic word jama‘a (gathering) and the Persian word khana (house, place), a jamatkhana is a place of gathering for worship as well as social and educational activities for the Nizari and Mustalian Ismailis. The Chisti Sufis, among other communities, also gather in jamatkhanas.

During the time of the Prophet, the community congregated in the masjid, a place of prostration (from the Arabic root sa-ja-da, meaning ‘to prostrate’). In the early Islamic era, the word masjid meant a place of prayer which could be any clean spot on earth. The first masjid, built in Medina in 622 CE, was primarily a designated space for the offering of canonical ritual prayers by Muslim congregations. Besides its religious function, masjid is also used as the centre of community life which can serve social, political and educational roles (IIS).

Over time, as Islam expanded and diverse interpretations arose, a variety of spaces of worship and gathering developed, with architectural styles reflecting the respective local cultures and materials.

Khaniqa/Khaniqah – from Persian, lit. ‘residence,’ the khaniqa is a term for a Sufi meeting house which serves as a residential teaching centre for Sufi disciples. A famous khaniqa was established by Muhammad ibn Karram (d. 839 CE) the founder of the Karramiyya tariqah. Khaniqahha are usually designed to house Sufis, provide places for communal worship, and feed the residents, guests and travellers (IIS).

Ribat – from the Arabic root ra-ba-ta meaning ‘to attach’ or ‘to link’; and for in certain Sufi traditions it means strengthening the heart. Ribat as a building could describe a small fort, a fortified place, or an urban establishment for mystics who gathered there to study, pray, and write. The earliest foundations of this kind of building date back to the first half-century of the ‘Abbasid period (750-1258 CE) (IIS).

Ribat Monastir, Sousse, Tunisia. Image: Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, Brown University

Zawiya – from the Arabic meaning ‘a corner,’ it is a Sufi place of worship referring to the corner of a mosque where a worshiper would isolate to perform dhikr, or may refer to a mausoleum of a saint or the founder of a specific Sufi tariqah. The names of these centres have varied according to location: zawiya and ribat were used mostly in the Maghrib (present-day Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia); khanaqah in Egypt, Syria, and Iran; khanagah from Iran to India (the term dargah is also used); and tekke in Turkish-speaking areas.

At the foundation ceremony of the Ismaili Centre, Dubai on 13 December 2003, His Highness Aga Khan IV reflected upon the co-existence of the diverse spaces of worship:

“For many centuries, a prominent feature of the Muslim religious landscape has been the variety of spaces of gathering co-existing harmoniously with the masjid, which in itself has accommodated a range of diverse institutional spaces for educational, social and reflective purposes. Historically serving communities of different interpretations and spiritual affiliations, these spaces have retained their cultural nomenclatures and characteristics, from ribat and zawiyya to khanaqa and jamatkhana.

The congregational space incorporated within the Ismaili Centre belongs to the historic category of jamatkhana, an institutional category that also serves a number of sister Sunni and Shia communities, in their respective contexts, in many parts of the world. Here, it will be space reserved for traditions and practices specific to the Shia Ismaili Tariqah of Islam.”

Speech

Sources:

Karim Jiwani, Muslim Spaces of Piety and Worship, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Oleg Grabar, “The Mosque,” Islam: Art and Architecture Edited by Markus Hattstein and Peter Delius. Cologne, Konenmann, 2000

~*~*~

Contributed to Ismailimail by Nimira Dewji. Nimira is an invited writer although she has contributed several articles in the past (view previous articles). She also has her own blog – Nimirasblog – where she writes short articles on Ismaili history and Muslim civilisations. When not researching and writing, Nimira volunteers at a shelter for those experiencing homelessness, and at a women’s shelter. She can be reached at [email protected].

https://ismailimail.blog/2022/01/14/twe ... re-canada/

Celebrating over a century of Ismaili community in Kenya

Friday, January 14, 2022

Khoja Mosque

Town Jamatkhana (Khoja Mosque) on Moi Avenue, Nairobi. The iconic religious and cultural centre marks its 100th anniversary on January 14, 2022.

File | Nation Media Group

By Azim Lakhani & Shamira Dostmohamed

By Azim Lakhani & Shamira Dostmohamed

What you need to know:

- The Ismailis, mainly migrants from the State of Gujarat in India, arrived to settle in Nairobi around 1900.

- Town Jamatkhana was gazetted as a historic monument under the National Museums of Kenya in 2001.

The majestic iconic Town Jamatkhana (religious and cultural centre), popularly known as Khoja Mosque, a landmark on Moi Avenue in Nairobi’s Central Business District, first opened its doors on January 14, 1922.

Its 100-year anniversary provides an opportunity to reflect on how such a monument symbolises the permanence of the Ismaili Muslim Community in Kenya, as well as catalyses the development of a neighbourhood, a city, indeed a nation.

Construction of the three-storeyed Victorian-style building commenced in 1920. The foyer features magnificent arches and moulded ceilings; an atrium floods the space with natural light; balustrades are finished in handcrafted timber; panelled timber doors sit in arched frames; many floors are finished in patterned terrazzo; and windows, some with stained glass patterns, are supported by timber frames.

Over time, the building, comprising prayer halls as well as spaces for social events and learning, has supported religious and social activities of the Ismailis.

The Ismailis, mainly migrants from the State of Gujarat in India, had arrived to settle in Nairobi around 1900. About the same time, following completion of the construction of the Kenya-Uganda Railway, Indian tradespeople from Kenya’s Coast made their way inland and settled in Nairobi. Town Jamatkhana became the focal point of new businesses and is credited with stimulating the growth of Bazaar Street, now Biashara (Kiswahili for trade/commerce) Street.

History of Ismailis in Nairobi