JUDAISM

Jewish community saves Muslim restaurant targeted in far-Right attack in Germany

Justin Huggler

The Telegraph Fri, March 5, 2021, 10:38 AM

Ismet Tekin owner of the Turkish Bistro in Halle that was attacked in 2019

Ismet Tekin owner of the Turkish Bistro in Halle that was attacked in 2019

The German Jewish community has intervened to save a Muslim-owned kebab restaurant targeted in a far-Right terror attack from going out of business because of the coronavirus pandemic.

With its slowly rotating kebab spits and stainless steel salad counter, Kiez-Döner in the eastern city of Halle is typical of countless Turkish fast food joints scattered across Germany.

In 2019 it made headlines around the world after it was caught up in a far-Right terror attack that also targeted a synagogue packed with worshippers marking Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar.

A bloodbath was averted when the lone gunman couldn’t force his way into the synagogue, but he turned his gun on a woman in the street making his way to Kiez-Döner, where he murdered a customer. Since then, the restaurant has become something of a shrine to the two victims, Jana Lange and Kevin Schwarze.

But Kiez-Döner has fallen on hard times. With Germany in lockdown since November and restaurants only allowed to sell takeaways, it was facing bankruptcy when the Jewish community stepped in.

The German Jewish Student Union launched an international fundraising drive around the world that brought in more than €30,000 (£26,000) to save the restaurant.

And a local Jewish leader paid for €1,000 (£1,000) of kebabs in advance, handing out coupons for members of the community to collect them.

“It’s really amazing what they did,” says Ismet Tekin, the restaurant's Turkish-born owner. “They did it out of solidarity, to show that we are together, that we can get through these times when we stand together.”

Mr Tekin says he isn’t interested in historic tensions and distrust between Jews and Muslims in the Middle East. “For me there are no tensions,” he says. “Religion is a private thing. Everyone is entitled to his beliefs.”

Kiez-Döner didn’t have many Jewish customers before 2019, he says — the Jewish community in Halle is very small. But in the wake of the attack many of its members became regulars, and they were among the first to learn of the restaurant’s business woes.

“The community did this because the synagogue and Kiez-Döner were both targets of the attack,” says Igor Matviyets, a member of the local Jewish community and a candidate in elections to the regional parliament in June.

“It’s very clear from what the gunman said that he targeted the restaurant because it didn’t represent his idea of what should be in Germany, just as the synagogue didn’t.”

The gunman, Stephan Balliet, railed against Jews, Muslims, immigrants and women in an online live stream of the attack, and released a manifesto in which he expressed the same views.

Mr Tekin has lived in Germany 13 years. He says the attack has not dimmed his desire to remain. “Of course I’ll stay. This is my home.”

https://currently.att.yahoo.com/news/je ... 13747.html

Justin Huggler

The Telegraph Fri, March 5, 2021, 10:38 AM

Ismet Tekin owner of the Turkish Bistro in Halle that was attacked in 2019

Ismet Tekin owner of the Turkish Bistro in Halle that was attacked in 2019

The German Jewish community has intervened to save a Muslim-owned kebab restaurant targeted in a far-Right terror attack from going out of business because of the coronavirus pandemic.

With its slowly rotating kebab spits and stainless steel salad counter, Kiez-Döner in the eastern city of Halle is typical of countless Turkish fast food joints scattered across Germany.

In 2019 it made headlines around the world after it was caught up in a far-Right terror attack that also targeted a synagogue packed with worshippers marking Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar.

A bloodbath was averted when the lone gunman couldn’t force his way into the synagogue, but he turned his gun on a woman in the street making his way to Kiez-Döner, where he murdered a customer. Since then, the restaurant has become something of a shrine to the two victims, Jana Lange and Kevin Schwarze.

But Kiez-Döner has fallen on hard times. With Germany in lockdown since November and restaurants only allowed to sell takeaways, it was facing bankruptcy when the Jewish community stepped in.

The German Jewish Student Union launched an international fundraising drive around the world that brought in more than €30,000 (£26,000) to save the restaurant.

And a local Jewish leader paid for €1,000 (£1,000) of kebabs in advance, handing out coupons for members of the community to collect them.

“It’s really amazing what they did,” says Ismet Tekin, the restaurant's Turkish-born owner. “They did it out of solidarity, to show that we are together, that we can get through these times when we stand together.”

Mr Tekin says he isn’t interested in historic tensions and distrust between Jews and Muslims in the Middle East. “For me there are no tensions,” he says. “Religion is a private thing. Everyone is entitled to his beliefs.”

Kiez-Döner didn’t have many Jewish customers before 2019, he says — the Jewish community in Halle is very small. But in the wake of the attack many of its members became regulars, and they were among the first to learn of the restaurant’s business woes.

“The community did this because the synagogue and Kiez-Döner were both targets of the attack,” says Igor Matviyets, a member of the local Jewish community and a candidate in elections to the regional parliament in June.

“It’s very clear from what the gunman said that he targeted the restaurant because it didn’t represent his idea of what should be in Germany, just as the synagogue didn’t.”

The gunman, Stephan Balliet, railed against Jews, Muslims, immigrants and women in an online live stream of the attack, and released a manifesto in which he expressed the same views.

Mr Tekin has lived in Germany 13 years. He says the attack has not dimmed his desire to remain. “Of course I’ll stay. This is my home.”

https://currently.att.yahoo.com/news/je ... 13747.html

Passover 2021 begins at sundown on March 27 and ends Sunday evening, April 4. The first Passover seder is on the evening of March 27, and the second Passover seder takes place on the evening of March 28.

Passover is a festival of freedom.

It commemorates the Israelites’ Exodus from Egypt, and their transition from slavery to freedom. The main ritual of Passover is the seder, which occurs on the first two night (in Israel just the first night) of the holiday — a festive meal that involves the re-telling of the Exodus through stories and song and the consumption of ritual foods, including matzah and maror (bitter herbs). The seder’s rituals and other readings are outlined in the Haggadah — today, many different versions of this Passover guide are available in print and online, and you can also create your own.

What are some Passover practices?

The central Passover practice is a set of intense dietary changes, mainly the absence of hametz, or foods with leaven. (Ashkenazi Jews also avoid kitniyot, a category of food that includes legumes.) In recent years, many Jews have compensated for the lack of grain by cooking with quinoa, although not all recognize it as kosher for Passover. The ecstatic cycle of psalms called Hallel is recited both at night and day (during the seder and morning prayers). Additionally, Passover commences a 49-day period called the Omer, which recalls the count between offerings brought to the ancient Temple in Jerusalem. This count culminates in the holiday of Shavuot, the anniversary of the receiving of the Torah at Sinai.

Passover is a festival of freedom.

It commemorates the Israelites’ Exodus from Egypt, and their transition from slavery to freedom. The main ritual of Passover is the seder, which occurs on the first two night (in Israel just the first night) of the holiday — a festive meal that involves the re-telling of the Exodus through stories and song and the consumption of ritual foods, including matzah and maror (bitter herbs). The seder’s rituals and other readings are outlined in the Haggadah — today, many different versions of this Passover guide are available in print and online, and you can also create your own.

What are some Passover practices?

The central Passover practice is a set of intense dietary changes, mainly the absence of hametz, or foods with leaven. (Ashkenazi Jews also avoid kitniyot, a category of food that includes legumes.) In recent years, many Jews have compensated for the lack of grain by cooking with quinoa, although not all recognize it as kosher for Passover. The ecstatic cycle of psalms called Hallel is recited both at night and day (during the seder and morning prayers). Additionally, Passover commences a 49-day period called the Omer, which recalls the count between offerings brought to the ancient Temple in Jerusalem. This count culminates in the holiday of Shavuot, the anniversary of the receiving of the Torah at Sinai.

Israel Reveals Newly Discovered Fragments of Dead Sea Scrolls

The finds, ranging from just a few millimeters to a thumbnail in size, are the first to be unearthed in archaeological excavations in the Judean Desert in about 60 years.

Watch video at:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/16/worl ... 778d3e6de3

JERUSALEM — Israeli researchers unveiled on Tuesday dozens of newly discovered Dead Sea Scroll fragments containing biblical texts dating back nearly 2,000 years, adding to the body of artifacts that have shed light on the history of Judaism, early Christian life and ancient humankind.

The parchment fragments, ranging from just a few millimeters to a thumbnail in size, are the first in about 60 years to have been unearthed in archaeological excavations in the Judean Desert. They were found as part of a four-year Israeli national project to prevent further looting of antiquities from the remote caves and crevices of the desert east and southeast of Jerusalem, which straddles the boundary of Israel and the occupied West Bank.

The project turned up many other rare and historic finds, including a large woven basket with a lid that has been dated to approximately 10,500 years ago and may be the oldest such intact basket in the world. The archaeologists also found a 6,000-year-old, partially mummified skeleton of a child buried in the fetal position and wrapped in a cloth.

“The desert team showed exceptional courage, dedication and devotion to purpose, rappelling down to caves located between heaven and earth,” said Israel Hasson, the departing director of the Israel Antiquities Authority, which is the custodian of some 15,000 fragments of the scrolls.

He added in a statement that their work in the caves involved “digging and sifting through them, enduring thick and suffocating dust, and returning with gifts of immeasurable worth for mankind.”

The Dead Sea Scrolls, mostly discovered during the last century, contain the earliest known copies of parts of almost every book of the Hebrew Bible, other than the Book of Esther, written on parchment and papyrus.

Dating from about the third century B.C. to the first century A.D., the biblical and apocryphal texts are widely considered to be among the most significant archaeological discoveries of the 20th century and remain the subject of heated academic debate around the world.

The arid conditions of the Judean Desert provided a unique environment for the natural preservation of artifacts and organic materials that would ordinarily not have withstood the test of time.

More..

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/16/worl ... 778d3e6de3

The finds, ranging from just a few millimeters to a thumbnail in size, are the first to be unearthed in archaeological excavations in the Judean Desert in about 60 years.

Watch video at:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/16/worl ... 778d3e6de3

JERUSALEM — Israeli researchers unveiled on Tuesday dozens of newly discovered Dead Sea Scroll fragments containing biblical texts dating back nearly 2,000 years, adding to the body of artifacts that have shed light on the history of Judaism, early Christian life and ancient humankind.

The parchment fragments, ranging from just a few millimeters to a thumbnail in size, are the first in about 60 years to have been unearthed in archaeological excavations in the Judean Desert. They were found as part of a four-year Israeli national project to prevent further looting of antiquities from the remote caves and crevices of the desert east and southeast of Jerusalem, which straddles the boundary of Israel and the occupied West Bank.

The project turned up many other rare and historic finds, including a large woven basket with a lid that has been dated to approximately 10,500 years ago and may be the oldest such intact basket in the world. The archaeologists also found a 6,000-year-old, partially mummified skeleton of a child buried in the fetal position and wrapped in a cloth.

“The desert team showed exceptional courage, dedication and devotion to purpose, rappelling down to caves located between heaven and earth,” said Israel Hasson, the departing director of the Israel Antiquities Authority, which is the custodian of some 15,000 fragments of the scrolls.

He added in a statement that their work in the caves involved “digging and sifting through them, enduring thick and suffocating dust, and returning with gifts of immeasurable worth for mankind.”

The Dead Sea Scrolls, mostly discovered during the last century, contain the earliest known copies of parts of almost every book of the Hebrew Bible, other than the Book of Esther, written on parchment and papyrus.

Dating from about the third century B.C. to the first century A.D., the biblical and apocryphal texts are widely considered to be among the most significant archaeological discoveries of the 20th century and remain the subject of heated academic debate around the world.

The arid conditions of the Judean Desert provided a unique environment for the natural preservation of artifacts and organic materials that would ordinarily not have withstood the test of time.

More..

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/16/worl ... 778d3e6de3

Israel Dead Sea Scrolls

The Israel Antiquities Authority displays newly discovered Dead Sea Scroll fragments at the Dead Sea scrolls conservation lab in Jerusalem, Tuesday, March 16, 2021. Israeli archaeologists on Tuesday announced the discovery of dozens of new Dead Sea Scroll fragments bearing a biblical text found in a desert cave and believed hidden during a Jewish revolt against Rome nearly 1,900 years ago. (AP Photo/Sebastian Scheiner)

JERUSALEM (AP) — Israeli archaeologists on Tuesday announced the discovery of dozens of Dead Sea Scroll fragments bearing a biblical text found in a desert cave and believed hidden during a Jewish revolt against Rome nearly 1,900 years ago.

The fragments of parchment bear lines of Greek text from the books of Zechariah and Nahum and have been dated around the first century based on the writing style, according to the Israel Antiquities Authority. They are the first new scrolls found in archaeological excavations in the desert south of Jerusalem in 60 years.

The Dead Sea Scrolls, a collection of Jewish texts found in desert caves in the West Bank near Qumran in the 1940s and 1950s, date from the third century B.C. to the first century A.D. They include the earliest known copies of biblical texts and documents outlining the beliefs of a little understood Jewish sect.

The roughly 80 new pieces are believed to belong to a set of parchment fragments found in a site in southern Israel known as the “Cave of Horror” — named for the 40 human skeletons found there during excavations in the 1960s — that also bear a Greek rendition of the Twelve Minor Prophets, a book in the Hebrew Bible. The cave is located in a remote canyon around 40 kilometers (25 miles) south of Jerusalem.

The artifacts were found during an operation in Israel and the occupied West Bank conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority to find scrolls and other artifacts to prevent possible plundering. Israel captured the West Bank in the 1967 war, and international law prohibits the removal of cultural property from occupied territory. The authority held a news conference Tuesday to unveil the discovery.

The fragments are believed to have been part of a scroll stashed away in the cave during the Bar Kochba Revolt, an armed Jewish uprising against Rome during the reign of Emperor Hadrian, between 132 and 136. Coins struck by rebels and arrowheads found in other caves in the region also hail from that period.

“We found a textual difference that has no parallel with any other manuscript, either in Hebrew or in Greek,” said Oren Ableman, a Dead Sea Scroll researcher with the Israel Antiquities Authority. He referred to slight variations in the Greek rendering of the Hebrew original compared to the Septuagint — a translation of the Hebrew Bible to Greek made in Egypt in the third and second centuries B.C.

“When we think about the biblical text, we think about something very static. It wasn’t static. There are slight differences and some of those differences are important,” said Joe Uziel, head of the antiquities authority's Dead Sea Scrolls unit. “Every little piece of information that we can add, we can understand a little bit better” how the Biblical text came into its traditional Hebrew form.

Alongside the Roman-era artifacts, the exhibit included far older discoveries of no lesser importance found during its sweep of more than 500 caves in the desert: the 6,000-year-old mummified skeleton of a child, an immense, complete woven basket from the Neolithic period, estimated to be 10,500 years old, and scores of other delicate organic materials preserved in caves’ arid climate.

In 1961, Israeli archaeologist Yohanan Aharoni excavated the “Cave of Horror” and his team found nine parchment fragments belonging to a scroll with texts from the Twelve Minor Prophets in Greek, and a scrap of Greek papyrus.

Since then, no new texts have been found during archaeological excavations, but many have turned up on the black market, apparently plundered from caves.

For the past four years, Israeli archaeologists have launched a major campaign to scour caves nestled in the precipitous canyons of the Judean Desert in search of scrolls and other rare artifacts. The aim is to find them before plunderers disturb the remote sites, destroying archaeological strata and data in search of antiquities bound for the black market.

Until now the hunt had only found a handful of parchment scraps that bore no text.

Amir Ganor, head of the antiquities theft prevention unit, said that since the commencement of the operation in 2017 there has been virtually no antiquities plundering in the Judean Desert, calling the operation a success.

“For the first time in 70 years, we were able to preempt the plunderers,” he said.

https://currently.att.yahoo.com/news/is ... 23667.html

The Israel Antiquities Authority displays newly discovered Dead Sea Scroll fragments at the Dead Sea scrolls conservation lab in Jerusalem, Tuesday, March 16, 2021. Israeli archaeologists on Tuesday announced the discovery of dozens of new Dead Sea Scroll fragments bearing a biblical text found in a desert cave and believed hidden during a Jewish revolt against Rome nearly 1,900 years ago. (AP Photo/Sebastian Scheiner)

JERUSALEM (AP) — Israeli archaeologists on Tuesday announced the discovery of dozens of Dead Sea Scroll fragments bearing a biblical text found in a desert cave and believed hidden during a Jewish revolt against Rome nearly 1,900 years ago.

The fragments of parchment bear lines of Greek text from the books of Zechariah and Nahum and have been dated around the first century based on the writing style, according to the Israel Antiquities Authority. They are the first new scrolls found in archaeological excavations in the desert south of Jerusalem in 60 years.

The Dead Sea Scrolls, a collection of Jewish texts found in desert caves in the West Bank near Qumran in the 1940s and 1950s, date from the third century B.C. to the first century A.D. They include the earliest known copies of biblical texts and documents outlining the beliefs of a little understood Jewish sect.

The roughly 80 new pieces are believed to belong to a set of parchment fragments found in a site in southern Israel known as the “Cave of Horror” — named for the 40 human skeletons found there during excavations in the 1960s — that also bear a Greek rendition of the Twelve Minor Prophets, a book in the Hebrew Bible. The cave is located in a remote canyon around 40 kilometers (25 miles) south of Jerusalem.

The artifacts were found during an operation in Israel and the occupied West Bank conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority to find scrolls and other artifacts to prevent possible plundering. Israel captured the West Bank in the 1967 war, and international law prohibits the removal of cultural property from occupied territory. The authority held a news conference Tuesday to unveil the discovery.

The fragments are believed to have been part of a scroll stashed away in the cave during the Bar Kochba Revolt, an armed Jewish uprising against Rome during the reign of Emperor Hadrian, between 132 and 136. Coins struck by rebels and arrowheads found in other caves in the region also hail from that period.

“We found a textual difference that has no parallel with any other manuscript, either in Hebrew or in Greek,” said Oren Ableman, a Dead Sea Scroll researcher with the Israel Antiquities Authority. He referred to slight variations in the Greek rendering of the Hebrew original compared to the Septuagint — a translation of the Hebrew Bible to Greek made in Egypt in the third and second centuries B.C.

“When we think about the biblical text, we think about something very static. It wasn’t static. There are slight differences and some of those differences are important,” said Joe Uziel, head of the antiquities authority's Dead Sea Scrolls unit. “Every little piece of information that we can add, we can understand a little bit better” how the Biblical text came into its traditional Hebrew form.

Alongside the Roman-era artifacts, the exhibit included far older discoveries of no lesser importance found during its sweep of more than 500 caves in the desert: the 6,000-year-old mummified skeleton of a child, an immense, complete woven basket from the Neolithic period, estimated to be 10,500 years old, and scores of other delicate organic materials preserved in caves’ arid climate.

In 1961, Israeli archaeologist Yohanan Aharoni excavated the “Cave of Horror” and his team found nine parchment fragments belonging to a scroll with texts from the Twelve Minor Prophets in Greek, and a scrap of Greek papyrus.

Since then, no new texts have been found during archaeological excavations, but many have turned up on the black market, apparently plundered from caves.

For the past four years, Israeli archaeologists have launched a major campaign to scour caves nestled in the precipitous canyons of the Judean Desert in search of scrolls and other rare artifacts. The aim is to find them before plunderers disturb the remote sites, destroying archaeological strata and data in search of antiquities bound for the black market.

Until now the hunt had only found a handful of parchment scraps that bore no text.

Amir Ganor, head of the antiquities theft prevention unit, said that since the commencement of the operation in 2017 there has been virtually no antiquities plundering in the Judean Desert, calling the operation a success.

“For the first time in 70 years, we were able to preempt the plunderers,” he said.

https://currently.att.yahoo.com/news/is ... 23667.html

WHAT PASSOVER TAUGHT ME ABOUT BEING BLACK

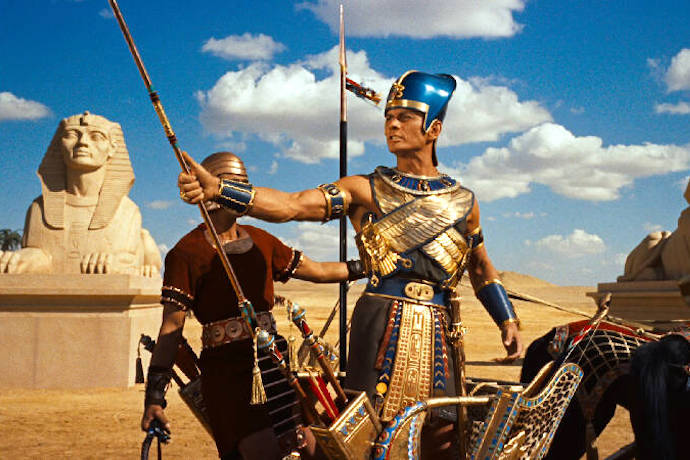

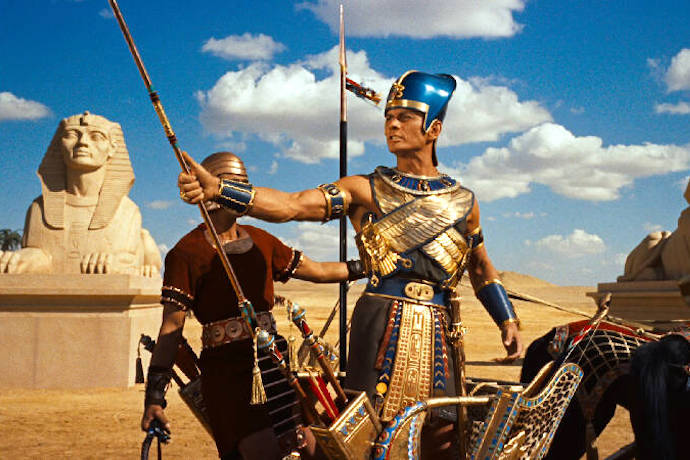

As Passover approaches this weekend I often reminisce about how, as a young child, the highlight of my Easter weekend wasn’t watching the Greatest Story Ever Told, The Robe, or other classic Easter movies. For me, it was watching Cecil B. Demille’s The Ten Commandments, starring Charleston Heston and Yul Brenner. I relished each time Brenner’s Ramses scowled at his viziers and exclaimed, “So let it be written, so let it be done.” My admiration for this cinematic villain was rivaled only by my admiration for Darth Vader. The annual viewing of the Exodus story is what cemented my Easter experience.

However, as a Black teenager growing up in the 1990s my relationship to The Ten Commandments changed. In an era influenced by Afrocentricity and politically conscious hip hop, this straightforward morality tale about slavery and freedom became complicated. The Egyptians were Africans, as my deep dive into Afrocentric literature revealed. And weren’t the Hebrews just foreign invaders who sought to form alliances with the enemies of ancient Kemet (Egypt)? Couple this with the breaking of the détente in the “Black-Jewish” relationship as the Nation of Islam’s Minister Louis Farrakhan and members of the American Jewish community were in the midst a rhetorical war of words over the historical record regarding Jewish participation in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade with the publication of the Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews. Now when I watched The Ten Commandments, I wasn’t so sure who was the hero and who was the villain.

Then something unexpected happened. I met a group of Hebrew Israelites from the Israeli School of Universal Practical Knowledge (ISUPK). To those unfamiliar—and even to those who are—the ISUPK are an enigmatic group. They believe that enslaved African and Indigenous populations of the western hemisphere are the genealogical descendants of the biblical Israelites. For the sake of space, I won’t go into all the particulars of their doctrine but suffice it to say that what drew me to this group was their iron-clad explanation for the existential and transgenerational suffering of Black and Indigenous people throughout the western hemisphere—or so I believed at the time.

Fast forward to the late 2000s and 2010s, with the advent of social media the beliefs of Hebrew Israelite groups such as the ISUPK have moved from public access TV stations to YouTube. Their teachings and beliefs have shifted from the margins of Black religious life to the mainstream. It’s not uncommon to hear an African American assert that “Black people are the true chosen people.” It’s become a regular occurrence for an African-American celebrity, entertainer, or athlete to post to their social media account that they’ve uncovered the “hidden truth” that Black people are “real Jews” to the chagrin of the mainstream media which, in a predictable knee jerk reaction, label them anti-Semites and hatemongers. Simply put, Hebrew Israelites are in style.

Within rabbinic Judaism, the High Holy Days (Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur) signify the most sacred period in the Jewish calendar. For Hebrew Israelites, however, Passover is the most symbolically important biblical holiday, as it’s the celebration of freedom over slavery. But more importantly it’s typological proof that the biblical God cares about Black people. For Hebrew Israelites, if God could hear the cries of their biblical ancestors then He will act again on behalf of their descendants in the urban centers of America, favelas of Brazil, shanties of Jamaica, and reservations of the American West.

For years, I would anticipate the arrival of spring and Passover season. Meticulously cleaning my house of leaven as I awaited this celebration of freedom. Now when I watched The Ten Commandments I was once again rooting for Moses (albeit a white one) and the Hebrews as they dueled with Ramses and the Egyptians.

But then something unexpected happened, I converted to rabbinic Judaism under the guidance of an African-American rabbi and within the context of a primarily African-American congregation. Observing the Passover seder communally with my congregation was exciting. As time progressed, however, Passover became further removed from my annual celebration of freedom from Egyptian slavery and the hope for the end of American bondage to debates over whether, as a non-Ashkenazi Jew, I should eat rice or not during the holiday and scavenger hunts for Kosher for Passover Coca-Cola. My conversion created a tension between my Black self and my Jewish self, and in the words of W.E.B. Du Bois, there were “two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

Although I do not think the sage of Great Barrington had me in mind when he penned those words in the Souls of Black Folk it was an apt description of the contested nature of my spiritual being. The more rabbinic I sought to become, the more Blackness was an issue in need of resolution.

The journey led me to leave my African-American congregation for a stint with Conservative Judaism and a flirtation with a local Chabad house to a trek to the North Side of Chicago to worship with Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews. Finally, I rounded out my trip with a brief fling with Reconstructionist Judaism, but the soul of my darker self became dimmer and dimmer with each stop—became almost unrecognizable to me. Eventually I abandoned the key tenet of Hebrew Israelite belief: that Black people in America were the lost tribes of Israel destined to languish and suffer in American captivity until God saw fit for our redemption.

Now I was Black and I was Jewish, but not a Black Jew—the two did not coexist together anymore. Jewishness could not explain my Blackness and vice versa. As a doctoral student in African-American Studies my research eventually led me to pose the previously unasked questions, Why was I Jewish? Did I need to be Jewish? If I was not Jewish because I was reclaiming my lost African ancestry, then why did I still need to be Jewish? While I loved Shabbat and Jewish holidays, keeping kosher, and living an overall observant lifestyle, the question remained: Why was I Jewish? The answer was equally unexpected: Passover had one final lesson to teach me.

Today I say that I transitioned from, rather than abandoned, Judaism. I learned that just as the Jewish people (which includes Africana Jews) throughout their history have created myths, rituals, and practices to survive and thrive through their persecutions, Black people in America have the same human right to create and tell sacred myths, develop rituals, and incorporate practices learned from others to ensure their survival.

I learned I need not be anybody else to be of spiritual worth. I learned I need not be “real,” “chosen,” or “lost”—that being Black is sufficient to be sacred. I learned that my prophets, sages, and saints could have names like Harriet, Martin, and Malcolm rather than just Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. I learned that Kwanzaa need not be from the distant African past to be of cultural and spiritual value. I came to value Juneteenth as a day of liberation that need not compete with or be a substitute for any other celebration of freedom.

Ultimately, from Passover I learned that every people should exercise the human right to tell their sacred story on their own terms, whether the rest of the world likes it or not. That is the meaning of freedom that I learned from Passover. “So let it be written, so let it be done!”

https://religiondispatches.org/what-pas ... eing-black

As Passover approaches this weekend I often reminisce about how, as a young child, the highlight of my Easter weekend wasn’t watching the Greatest Story Ever Told, The Robe, or other classic Easter movies. For me, it was watching Cecil B. Demille’s The Ten Commandments, starring Charleston Heston and Yul Brenner. I relished each time Brenner’s Ramses scowled at his viziers and exclaimed, “So let it be written, so let it be done.” My admiration for this cinematic villain was rivaled only by my admiration for Darth Vader. The annual viewing of the Exodus story is what cemented my Easter experience.

However, as a Black teenager growing up in the 1990s my relationship to The Ten Commandments changed. In an era influenced by Afrocentricity and politically conscious hip hop, this straightforward morality tale about slavery and freedom became complicated. The Egyptians were Africans, as my deep dive into Afrocentric literature revealed. And weren’t the Hebrews just foreign invaders who sought to form alliances with the enemies of ancient Kemet (Egypt)? Couple this with the breaking of the détente in the “Black-Jewish” relationship as the Nation of Islam’s Minister Louis Farrakhan and members of the American Jewish community were in the midst a rhetorical war of words over the historical record regarding Jewish participation in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade with the publication of the Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews. Now when I watched The Ten Commandments, I wasn’t so sure who was the hero and who was the villain.

Then something unexpected happened. I met a group of Hebrew Israelites from the Israeli School of Universal Practical Knowledge (ISUPK). To those unfamiliar—and even to those who are—the ISUPK are an enigmatic group. They believe that enslaved African and Indigenous populations of the western hemisphere are the genealogical descendants of the biblical Israelites. For the sake of space, I won’t go into all the particulars of their doctrine but suffice it to say that what drew me to this group was their iron-clad explanation for the existential and transgenerational suffering of Black and Indigenous people throughout the western hemisphere—or so I believed at the time.

Fast forward to the late 2000s and 2010s, with the advent of social media the beliefs of Hebrew Israelite groups such as the ISUPK have moved from public access TV stations to YouTube. Their teachings and beliefs have shifted from the margins of Black religious life to the mainstream. It’s not uncommon to hear an African American assert that “Black people are the true chosen people.” It’s become a regular occurrence for an African-American celebrity, entertainer, or athlete to post to their social media account that they’ve uncovered the “hidden truth” that Black people are “real Jews” to the chagrin of the mainstream media which, in a predictable knee jerk reaction, label them anti-Semites and hatemongers. Simply put, Hebrew Israelites are in style.

Within rabbinic Judaism, the High Holy Days (Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur) signify the most sacred period in the Jewish calendar. For Hebrew Israelites, however, Passover is the most symbolically important biblical holiday, as it’s the celebration of freedom over slavery. But more importantly it’s typological proof that the biblical God cares about Black people. For Hebrew Israelites, if God could hear the cries of their biblical ancestors then He will act again on behalf of their descendants in the urban centers of America, favelas of Brazil, shanties of Jamaica, and reservations of the American West.

For years, I would anticipate the arrival of spring and Passover season. Meticulously cleaning my house of leaven as I awaited this celebration of freedom. Now when I watched The Ten Commandments I was once again rooting for Moses (albeit a white one) and the Hebrews as they dueled with Ramses and the Egyptians.

But then something unexpected happened, I converted to rabbinic Judaism under the guidance of an African-American rabbi and within the context of a primarily African-American congregation. Observing the Passover seder communally with my congregation was exciting. As time progressed, however, Passover became further removed from my annual celebration of freedom from Egyptian slavery and the hope for the end of American bondage to debates over whether, as a non-Ashkenazi Jew, I should eat rice or not during the holiday and scavenger hunts for Kosher for Passover Coca-Cola. My conversion created a tension between my Black self and my Jewish self, and in the words of W.E.B. Du Bois, there were “two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

Although I do not think the sage of Great Barrington had me in mind when he penned those words in the Souls of Black Folk it was an apt description of the contested nature of my spiritual being. The more rabbinic I sought to become, the more Blackness was an issue in need of resolution.

The journey led me to leave my African-American congregation for a stint with Conservative Judaism and a flirtation with a local Chabad house to a trek to the North Side of Chicago to worship with Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews. Finally, I rounded out my trip with a brief fling with Reconstructionist Judaism, but the soul of my darker self became dimmer and dimmer with each stop—became almost unrecognizable to me. Eventually I abandoned the key tenet of Hebrew Israelite belief: that Black people in America were the lost tribes of Israel destined to languish and suffer in American captivity until God saw fit for our redemption.

Now I was Black and I was Jewish, but not a Black Jew—the two did not coexist together anymore. Jewishness could not explain my Blackness and vice versa. As a doctoral student in African-American Studies my research eventually led me to pose the previously unasked questions, Why was I Jewish? Did I need to be Jewish? If I was not Jewish because I was reclaiming my lost African ancestry, then why did I still need to be Jewish? While I loved Shabbat and Jewish holidays, keeping kosher, and living an overall observant lifestyle, the question remained: Why was I Jewish? The answer was equally unexpected: Passover had one final lesson to teach me.

Today I say that I transitioned from, rather than abandoned, Judaism. I learned that just as the Jewish people (which includes Africana Jews) throughout their history have created myths, rituals, and practices to survive and thrive through their persecutions, Black people in America have the same human right to create and tell sacred myths, develop rituals, and incorporate practices learned from others to ensure their survival.

I learned I need not be anybody else to be of spiritual worth. I learned I need not be “real,” “chosen,” or “lost”—that being Black is sufficient to be sacred. I learned that my prophets, sages, and saints could have names like Harriet, Martin, and Malcolm rather than just Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. I learned that Kwanzaa need not be from the distant African past to be of cultural and spiritual value. I came to value Juneteenth as a day of liberation that need not compete with or be a substitute for any other celebration of freedom.

Ultimately, from Passover I learned that every people should exercise the human right to tell their sacred story on their own terms, whether the rest of the world likes it or not. That is the meaning of freedom that I learned from Passover. “So let it be written, so let it be done!”

https://religiondispatches.org/what-pas ... eing-black

My Son’s Yeshiva Is Breaking the Law

Ultra-Orthodox schools must provide a proper education, but politicians aren’t holding them accountable.

Watch video at:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/07/opin ... 778d3e6de3

What do you want to be when you grow up? That’s not a common question for boys attending ultra-Orthodox yeshivas in New York. That’s because many of these schools focus on Judaic studies, preparing students for a life of religious scholarship — at the expense of basic reading, writing, math and science. New York State law mandates that private and religious schools provide a curriculum equivalent to that of public schools, and a 2019 report by New York City’s Department of Education found that only two of the 28 yeshivas it investigated met these requirements. This is especially problematic, considering that the city’s yeshivas receive over $100 million in state funds annually.

Authorities have failed to enforce the laws, allowing the community, which is a strong and unified voting bloc, to disregard secular education requirements. In the video above, a mother pleads with city and state officials to enforce the law so her son can receive one of the most basic rights: education.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/07/opin ... 778d3e6de3

Ultra-Orthodox schools must provide a proper education, but politicians aren’t holding them accountable.

Watch video at:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/07/opin ... 778d3e6de3

What do you want to be when you grow up? That’s not a common question for boys attending ultra-Orthodox yeshivas in New York. That’s because many of these schools focus on Judaic studies, preparing students for a life of religious scholarship — at the expense of basic reading, writing, math and science. New York State law mandates that private and religious schools provide a curriculum equivalent to that of public schools, and a 2019 report by New York City’s Department of Education found that only two of the 28 yeshivas it investigated met these requirements. This is especially problematic, considering that the city’s yeshivas receive over $100 million in state funds annually.

Authorities have failed to enforce the laws, allowing the community, which is a strong and unified voting bloc, to disregard secular education requirements. In the video above, a mother pleads with city and state officials to enforce the law so her son can receive one of the most basic rights: education.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/07/opin ... 778d3e6de3

BATTLE OF ANTISEMITISM DEFINITIONS IS ACTUALLY A PROXY WAR FOR CRITICISM OF ISRAEL

Last month, a global consortium of leading scholars released the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism (JDA), the product of a year-long labor to produce a new working definition of antisemitism that builds upon the widely-cited, but nearly as widely critiqued and abused, text of the International Holocaust Remembrance Association (IHRA). In the words of its authors, the JDA seeks “to provide a usable, concise, and historically-informed core definition of antisemitism with a set of guidelines.” In doing so, it aims to “strengthen the fight against antisemitism by clarifying what it is and how it is manifested,” while also protecting—and this is the key difference—“a space for an open debate about the vexed question of the future of Israel/Palestine.”

What exactly is at stake here? Everyone largely agrees on the nature of antisemitism. Scholars understand its core myths, pre-modern and modern, such as Jews constituting a single, global organism conspiring to conquer and destroy the world, led by a powerful “international Jew”—think Rothschild or George Soros—controlling vast populations and wealth.

The real debate is about criticizing Israel. Although IHRA notes the importance of context, in practice its vague language and large net has been misused to target pro-Palestinian advocacy on college campuses and in legislation. For example, IHRA’s concern about criticizing Israel by a “double standard” has often been interpreted to mean that anyone who protests Israeli human rights violations without equal attention to other countries has a “double standard” and is therefore presumed guilty of antisemitism. It opens up almost any criticism of Israel to that charge.

The JDA addresses this and other problems with specific examples of common anti-Israel rhetoric that crosses the line to antisemitism and specific examples of common rhetoric or actions (e.g. boycott) that do not. The list of signatures and subsequent endorsements is impressive, although there has been heated pushback by those who insist that the IHRA definition must be maintained. Indeed, one respondent—David Hirsh, author of Contemporary Leftwing Antisemitism (the focus of his activism)—accused the authors and supporters of the JDA of composing the definition not to fight antisemitism but to “fight efforts to fight antisemitism”; of standing with antisemites to protect them!

This is an outrageous attack against some of the most respected scholars and Jewish leaders in the world. In fact, the JDA is committed to fighting antisemitism while also preserving free discourse about Israel/Palestine, arguing that its clearer language accomplishes both more successfully. It lowers the ability of activists and lawmakers to silence political voices favoring Palestinian rights while also raising the ability of Jews to build critical alliances with other vulnerable minorities.

While advocates of the JDA hold a wide variety of beliefs about the future of Israel/Palestine—whether two states, a binational state, or some sort of confederation—all are committed to equality for everyone who currently lives “between the river and the sea.” This means that Jewish security cannot justify Jewish supremacy or Palestinian suffering, and that arguments against Jewish supremacy are certainly not antisemitic. Thus the debate ultimately hinges on whether or not calls for an end to Jewish supremacy—even while insisting that equality means Jewish equality as well—are antisemitic.

And this, in turn, reflects a fundamental transformation in American Judaism over the past half century.

In my youth, American Jews forged (in both senses of the word) a pluralist community through Holocaust commemoration and Israel celebration and worship. I don’t use that word worship lightly. Many of us were raised to worship Israel, and we manifested that devotion through innovative myths and rituals, from dance to liturgy and beyond. This was a core of the curriculum of the Jewish day school I attended for nine years, for example, far more than textual fluency or law. Jewish denominations struggled to respect each other as authentic or even legitimate, but with few exceptions they could commemorate the Holocaust and “walk with Israel” together, both literally and metaphorically.

Today, the Holocaust and Israel are precisely the wedges that most divide Jews, and their roles have grown clearer in the last few years as a result of the rise of global fascism (including Trumpism) and the move of Israel towards apartheid, with the entrenchment of the occupation and land appropriations, passage of legislation like the nation-state law, and the legitimization of open kahanists now entering knesset and possibly the government.

For some, the lesson of the Holocaust is “never again to us”; “never again” as Meir Kahane meant it when he popularized the phrase in the title of his famous book. It means a justification and even celebration of violence and oppression if deemed necessary tools in service of Jewish power. For others, the lesson is universal, “never again to anyone,” with a particularly keen awareness that Jews are no different than anyone else and are therefore just as likely to abuse their power in the name of nationalism and “self-defense” as anyone else.

This division has serious ramifications in terms of Jewish political choices. For the universalists, the key moral choice—and the choice that will best protect Jewish lives—is intersectional alliances with other minorities, since antisemitism exists as part of a worldview connected to defenses of hierarchy and oppression that affect us all, though some more than others. (American Jews are hardly as vulnerable to discrimination and violence as African Americans, for example, nor do they suffer from the legacy of four centuries of enslavement, expropriation and discrimination.) Political differences about Israel within this camp are far less important than the shared goal of defeating a worldview that seeks our joint oppression.

For those following Kahane’s meaning, the key alliance is with power, including (perhaps especially) authoritarian power that backs Jews, or at least pretends to do so. Of course, it’s not really backing all Jews. The key question is who or what it’s backing, which brings us back to the elephant in the discussion: Israel. Donald Trump, Victor Orban and the other despots with fascist tendencies aren’t backing Jews qua Jews. They’re backing Jewish supremacy in Israel/Palestine while stoking antisemitic mythology at home as part of a racist worldview.

This returns us to the division between these two definitions of antisemitism and the two competing paradigms in Jewish approaches to Israel. One is based on the fundamental assumption of the need to preserve Jewish supremacy. In this vision, the spectrum of “legitimate” (and thus “not antisemitic”) discourse on Israel runs from “two states someday” (i.e. de facto apartheid “for now,” but “someday,” based on Israeli standards, there can exist an eviscerated, non-sovereign Palestinian entity subject to Israeli incursion and rules) to Kahanism, whether implied in Netanyahu or explicit in his “Religious Zionist” allies, none of whom are even condemned anymore by mainstream American Jewish organizations, as they were two years ago.

The Israeli writer and public intellectual Yossi Klein Halevi made this clear to me in a recent interview, insisting that those like Naftali Bennett who advocate formal annexation without extending democracy (although he opposes them) constitute a legitimate part of the conversation, while Peter Beinart, who wrote a widely circulated article calling for a single bi-national state, does not. Other colleagues have said the same.

This is the division: equality vs. Jewish supremacy as the fundamental axiom of legitimacy.Advocating for the right of return for Palestinian refugees (even as something that must be negotiated), or even for Palestinian equality in all the land Israel now controls, is called “antisemitic,” “liquidationist” and is explicitly equated with the “call for Israel’s destruction” in this worldview. Only solutions that advocate Jewish supremacy are legitimate in this mindset. These are Orwellian distortions that obfuscate the distinction between a call for equality and the most extreme rhetoric of Hamas, and responds to any call for human rights with reference to security threats or whataboutisms—or they call themselves moderate because they lament Palestinian treatment and hope for two states “some day.”

A second approach to Israel is based on the fundamental right of equality. There are some in this camp who still advocate two states—two truly sovereign states based on a recognition of the extensive de facto annexation that’s already happened and must be reversed—though most tend to suggest some sort of confederation or binational entity is necessary. Others, like myself, avoid promoting any particular solution and simply want to describe the reality on the ground (i.e. de facto apartheid in a one-state reality) while pushing for true equality to replace Jewish supremacy as the fundamental value guiding future solutions.

This is the division: equality vs. Jewish supremacy as the fundamental axiom of legitimacy. And this is why Israel is not only the dividing point of Jews today, but also sits at the heart of conversations about antisemitism like IHRA and the JDA. The debate ultimately comes down to Israel and whether discourse that calls for an end to Jewish supremacy—even while insisting that equality means Jewish equality too—is antisemitic. IHRA can be easily used to make that case and the JDA cannot. Those in the camp of Jewish power must cling to the IHRA “working definition” as God’s final word on antisemitism in order to use the charge to suppress challenges to that power.

It’s heating up now not principally because antisemitism is getting worse, though it is, but because Israel is growing increasingly committed to its apartheid occupation of the West Bank and deepening discrimination against Palestinian citizens through legislation like the nation-state law. Israel’s choices—at the ballot box and beyond—are making the case for Israel harder to make.

Criticism of Israel and accusations of apartheid thus resonate more forcefully and, for some, more dangerously. This creates a state of anxiety whereby boundaries of critique must be limited, managed, even curtailed, and the accusation of ‘antisemitism’ is one way to do it. But this comes at a cost, not only the moral cost of using this charge to suppress legitimate political advocacy, but also at the practical cost of undermining the struggle against actual antisemitism by inflating its use and undermining vital alliances.

Correction: An earlier version of this essay noted that Yossi Klein Halevi recognized Itamar Ben Gvir in an interview as a legitimate part of the political conversation. In fact, he only mentioned annexationists generally and has on other occasions condemned Ben Gvir. The author regrets the error.

https://religiondispatches.org/battle-o ... -of-israel

Last month, a global consortium of leading scholars released the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism (JDA), the product of a year-long labor to produce a new working definition of antisemitism that builds upon the widely-cited, but nearly as widely critiqued and abused, text of the International Holocaust Remembrance Association (IHRA). In the words of its authors, the JDA seeks “to provide a usable, concise, and historically-informed core definition of antisemitism with a set of guidelines.” In doing so, it aims to “strengthen the fight against antisemitism by clarifying what it is and how it is manifested,” while also protecting—and this is the key difference—“a space for an open debate about the vexed question of the future of Israel/Palestine.”

What exactly is at stake here? Everyone largely agrees on the nature of antisemitism. Scholars understand its core myths, pre-modern and modern, such as Jews constituting a single, global organism conspiring to conquer and destroy the world, led by a powerful “international Jew”—think Rothschild or George Soros—controlling vast populations and wealth.

The real debate is about criticizing Israel. Although IHRA notes the importance of context, in practice its vague language and large net has been misused to target pro-Palestinian advocacy on college campuses and in legislation. For example, IHRA’s concern about criticizing Israel by a “double standard” has often been interpreted to mean that anyone who protests Israeli human rights violations without equal attention to other countries has a “double standard” and is therefore presumed guilty of antisemitism. It opens up almost any criticism of Israel to that charge.

The JDA addresses this and other problems with specific examples of common anti-Israel rhetoric that crosses the line to antisemitism and specific examples of common rhetoric or actions (e.g. boycott) that do not. The list of signatures and subsequent endorsements is impressive, although there has been heated pushback by those who insist that the IHRA definition must be maintained. Indeed, one respondent—David Hirsh, author of Contemporary Leftwing Antisemitism (the focus of his activism)—accused the authors and supporters of the JDA of composing the definition not to fight antisemitism but to “fight efforts to fight antisemitism”; of standing with antisemites to protect them!

This is an outrageous attack against some of the most respected scholars and Jewish leaders in the world. In fact, the JDA is committed to fighting antisemitism while also preserving free discourse about Israel/Palestine, arguing that its clearer language accomplishes both more successfully. It lowers the ability of activists and lawmakers to silence political voices favoring Palestinian rights while also raising the ability of Jews to build critical alliances with other vulnerable minorities.

While advocates of the JDA hold a wide variety of beliefs about the future of Israel/Palestine—whether two states, a binational state, or some sort of confederation—all are committed to equality for everyone who currently lives “between the river and the sea.” This means that Jewish security cannot justify Jewish supremacy or Palestinian suffering, and that arguments against Jewish supremacy are certainly not antisemitic. Thus the debate ultimately hinges on whether or not calls for an end to Jewish supremacy—even while insisting that equality means Jewish equality as well—are antisemitic.

And this, in turn, reflects a fundamental transformation in American Judaism over the past half century.

In my youth, American Jews forged (in both senses of the word) a pluralist community through Holocaust commemoration and Israel celebration and worship. I don’t use that word worship lightly. Many of us were raised to worship Israel, and we manifested that devotion through innovative myths and rituals, from dance to liturgy and beyond. This was a core of the curriculum of the Jewish day school I attended for nine years, for example, far more than textual fluency or law. Jewish denominations struggled to respect each other as authentic or even legitimate, but with few exceptions they could commemorate the Holocaust and “walk with Israel” together, both literally and metaphorically.

Today, the Holocaust and Israel are precisely the wedges that most divide Jews, and their roles have grown clearer in the last few years as a result of the rise of global fascism (including Trumpism) and the move of Israel towards apartheid, with the entrenchment of the occupation and land appropriations, passage of legislation like the nation-state law, and the legitimization of open kahanists now entering knesset and possibly the government.

For some, the lesson of the Holocaust is “never again to us”; “never again” as Meir Kahane meant it when he popularized the phrase in the title of his famous book. It means a justification and even celebration of violence and oppression if deemed necessary tools in service of Jewish power. For others, the lesson is universal, “never again to anyone,” with a particularly keen awareness that Jews are no different than anyone else and are therefore just as likely to abuse their power in the name of nationalism and “self-defense” as anyone else.

This division has serious ramifications in terms of Jewish political choices. For the universalists, the key moral choice—and the choice that will best protect Jewish lives—is intersectional alliances with other minorities, since antisemitism exists as part of a worldview connected to defenses of hierarchy and oppression that affect us all, though some more than others. (American Jews are hardly as vulnerable to discrimination and violence as African Americans, for example, nor do they suffer from the legacy of four centuries of enslavement, expropriation and discrimination.) Political differences about Israel within this camp are far less important than the shared goal of defeating a worldview that seeks our joint oppression.

For those following Kahane’s meaning, the key alliance is with power, including (perhaps especially) authoritarian power that backs Jews, or at least pretends to do so. Of course, it’s not really backing all Jews. The key question is who or what it’s backing, which brings us back to the elephant in the discussion: Israel. Donald Trump, Victor Orban and the other despots with fascist tendencies aren’t backing Jews qua Jews. They’re backing Jewish supremacy in Israel/Palestine while stoking antisemitic mythology at home as part of a racist worldview.

This returns us to the division between these two definitions of antisemitism and the two competing paradigms in Jewish approaches to Israel. One is based on the fundamental assumption of the need to preserve Jewish supremacy. In this vision, the spectrum of “legitimate” (and thus “not antisemitic”) discourse on Israel runs from “two states someday” (i.e. de facto apartheid “for now,” but “someday,” based on Israeli standards, there can exist an eviscerated, non-sovereign Palestinian entity subject to Israeli incursion and rules) to Kahanism, whether implied in Netanyahu or explicit in his “Religious Zionist” allies, none of whom are even condemned anymore by mainstream American Jewish organizations, as they were two years ago.

The Israeli writer and public intellectual Yossi Klein Halevi made this clear to me in a recent interview, insisting that those like Naftali Bennett who advocate formal annexation without extending democracy (although he opposes them) constitute a legitimate part of the conversation, while Peter Beinart, who wrote a widely circulated article calling for a single bi-national state, does not. Other colleagues have said the same.

This is the division: equality vs. Jewish supremacy as the fundamental axiom of legitimacy.Advocating for the right of return for Palestinian refugees (even as something that must be negotiated), or even for Palestinian equality in all the land Israel now controls, is called “antisemitic,” “liquidationist” and is explicitly equated with the “call for Israel’s destruction” in this worldview. Only solutions that advocate Jewish supremacy are legitimate in this mindset. These are Orwellian distortions that obfuscate the distinction between a call for equality and the most extreme rhetoric of Hamas, and responds to any call for human rights with reference to security threats or whataboutisms—or they call themselves moderate because they lament Palestinian treatment and hope for two states “some day.”

A second approach to Israel is based on the fundamental right of equality. There are some in this camp who still advocate two states—two truly sovereign states based on a recognition of the extensive de facto annexation that’s already happened and must be reversed—though most tend to suggest some sort of confederation or binational entity is necessary. Others, like myself, avoid promoting any particular solution and simply want to describe the reality on the ground (i.e. de facto apartheid in a one-state reality) while pushing for true equality to replace Jewish supremacy as the fundamental value guiding future solutions.

This is the division: equality vs. Jewish supremacy as the fundamental axiom of legitimacy. And this is why Israel is not only the dividing point of Jews today, but also sits at the heart of conversations about antisemitism like IHRA and the JDA. The debate ultimately comes down to Israel and whether discourse that calls for an end to Jewish supremacy—even while insisting that equality means Jewish equality too—is antisemitic. IHRA can be easily used to make that case and the JDA cannot. Those in the camp of Jewish power must cling to the IHRA “working definition” as God’s final word on antisemitism in order to use the charge to suppress challenges to that power.

It’s heating up now not principally because antisemitism is getting worse, though it is, but because Israel is growing increasingly committed to its apartheid occupation of the West Bank and deepening discrimination against Palestinian citizens through legislation like the nation-state law. Israel’s choices—at the ballot box and beyond—are making the case for Israel harder to make.

Criticism of Israel and accusations of apartheid thus resonate more forcefully and, for some, more dangerously. This creates a state of anxiety whereby boundaries of critique must be limited, managed, even curtailed, and the accusation of ‘antisemitism’ is one way to do it. But this comes at a cost, not only the moral cost of using this charge to suppress legitimate political advocacy, but also at the practical cost of undermining the struggle against actual antisemitism by inflating its use and undermining vital alliances.

Correction: An earlier version of this essay noted that Yossi Klein Halevi recognized Itamar Ben Gvir in an interview as a legitimate part of the political conversation. In fact, he only mentioned annexationists generally and has on other occasions condemned Ben Gvir. The author regrets the error.

https://religiondispatches.org/battle-o ... -of-israel

Hundreds of Jewish supremacists chant 'Death to Arabs' as tensions boil over in Jerusalem clashes

Erin Snodgrass

INSIDER Thu, April 22, 2021, 9:38 PM

A groupd of far-right Jewish extremists clashed with Arab crowds in Jerusalem Thursday night.

Members of the supremacist group, Lehava, chanted "death to Arabs" as they marched to the Old City.

Police were able to separate the two crowds, but The Jerusalem Post still reported incidents of violence and arrests.

Planned protests among far-right Jewish extremists and Arab crowds escalated in Jerusalem's Old City Thursday night and early Friday morning amid increasing tensions in the city.

The head of the Jewish supremacist group Lehava, announced Wednesday that its activists would march from Zion Square to Damascus Gate on Thursday in protest of recent violence toward Jews, including assaults that have been filmed and uploaded to TikTok, according to The Times of Israel.

Members of the group, which opposes the assimilation and coexistence of Jews and non-Jews, organized on the messaging app WhatsApp and planned to bring weapons, the outlet said. A report on the Mynet Jerusalem news site said Lehava members were told to attack as many Arabs as possible, according to The Times of Israel.

In addition to a rise in anti-Jewish violence, increasing attacks on Arabs have been reported in the city, including Jewish youth throwing rocks at vehicles while chanting "death to Arabs."

As Israeli police deployed Thursday night, attempting to keep Lehava demonstrators away from crowds of counter-protesters who had gathered at Damascus Gate, hundreds of Jewish extremists chanted "death to Arabs.," according to Haaretz.

Authorities were also working to prevent Lehava members from clashing with Israelis who came to protest the march, the outlet reported.

The Jerusalem Post reported that police had successfully diverted Lehava protesters and Arab crowds in different directions of the city, after a brief meeting between the two at Damascus Gate that resulted in incidents of dumpster fires, bottle-throwing, and rock-throwing.

According to the outlet, Arab youth lit fireworks near Damascus Gate, calling out "Allahu Akhbar," while Lehava members carried signs that read "Death to terrorists" and chanted "Death to Arabs" and "Revenge."

Officers reportedly used stun grenades to break up the violence and continued performing security checks in the area throughout the night.

Haaretz reported a variety of injuries and arrests, including a Palestinian woman who was reportedly maced in the face by a Jewish man and the arrest of four Palestinians accused of attacking a passerby.

The Palestinian Red Crescent, a humanitarian organization, has reported 25 injured so far, according to Haaretz.

The violence comes amid nightly clashes and fighting between Palestinians and Israelis during Ramadan in the city, Reuters reported. Palestinians have reportedly previously clashed with authorities over a dispute regarding evening gatherings at Damascus Gate following the breaking of the daily fast during the Muslim holy month.

https://currently.att.yahoo.com/news/hu ... 36161.html

Erin Snodgrass

INSIDER Thu, April 22, 2021, 9:38 PM

A groupd of far-right Jewish extremists clashed with Arab crowds in Jerusalem Thursday night.

Members of the supremacist group, Lehava, chanted "death to Arabs" as they marched to the Old City.

Police were able to separate the two crowds, but The Jerusalem Post still reported incidents of violence and arrests.

Planned protests among far-right Jewish extremists and Arab crowds escalated in Jerusalem's Old City Thursday night and early Friday morning amid increasing tensions in the city.

The head of the Jewish supremacist group Lehava, announced Wednesday that its activists would march from Zion Square to Damascus Gate on Thursday in protest of recent violence toward Jews, including assaults that have been filmed and uploaded to TikTok, according to The Times of Israel.

Members of the group, which opposes the assimilation and coexistence of Jews and non-Jews, organized on the messaging app WhatsApp and planned to bring weapons, the outlet said. A report on the Mynet Jerusalem news site said Lehava members were told to attack as many Arabs as possible, according to The Times of Israel.

In addition to a rise in anti-Jewish violence, increasing attacks on Arabs have been reported in the city, including Jewish youth throwing rocks at vehicles while chanting "death to Arabs."

As Israeli police deployed Thursday night, attempting to keep Lehava demonstrators away from crowds of counter-protesters who had gathered at Damascus Gate, hundreds of Jewish extremists chanted "death to Arabs.," according to Haaretz.

Authorities were also working to prevent Lehava members from clashing with Israelis who came to protest the march, the outlet reported.

The Jerusalem Post reported that police had successfully diverted Lehava protesters and Arab crowds in different directions of the city, after a brief meeting between the two at Damascus Gate that resulted in incidents of dumpster fires, bottle-throwing, and rock-throwing.

According to the outlet, Arab youth lit fireworks near Damascus Gate, calling out "Allahu Akhbar," while Lehava members carried signs that read "Death to terrorists" and chanted "Death to Arabs" and "Revenge."

Officers reportedly used stun grenades to break up the violence and continued performing security checks in the area throughout the night.

Haaretz reported a variety of injuries and arrests, including a Palestinian woman who was reportedly maced in the face by a Jewish man and the arrest of four Palestinians accused of attacking a passerby.

The Palestinian Red Crescent, a humanitarian organization, has reported 25 injured so far, according to Haaretz.

The violence comes amid nightly clashes and fighting between Palestinians and Israelis during Ramadan in the city, Reuters reported. Palestinians have reportedly previously clashed with authorities over a dispute regarding evening gatherings at Damascus Gate following the breaking of the daily fast during the Muslim holy month.

https://currently.att.yahoo.com/news/hu ... 36161.html

Famine in the Bible is more than a curse: It is a signal of change and a chance for a new beginning

Joel Baden, Professor of Hebrew Bible, Yale Divinity School

The Conversation Wed, April 21, 2021, 7:24 AM

As the coronavirus spread rapidly around the world last year, the United Nations warned that the economic disruption of the pandemic could result in famines of “biblical proportions.”

The choice of words conveys more than just scale. Biblical stories of devastating famines are familiar to many. As a scholar of the Hebrew Bible, I understand that famines in biblical times were interpreted as more than mere natural occurrences. The authors of the Hebrew Bible used famine as a mechanism of divine wrath and destruction – but also as a storytelling device, a way to move the narrative forward.

When the heavens don’t open

Underlying the texts about famine in the Hebrew Bible was the constant threat and recurring reality of famine in ancient Israel.

Israel occupied the rocky highlands of Canaan – the area of present-day Jerusalem and the hills to the north of it – rather than fertile coastal plains. Even in the best of years, it took enormous effort to coax sufficient sustenance out of the ground. The rainy seasons were brief; any precipitation less than normal could be devastating.

Across the ancient Near East, drought and famine were feared. In the 13th century B.C., nearly all of the Eastern Mediterranean civilizations collapsed because of a prolonged drought.

For the biblical authors, rain was a blessing and drought a curse – quite literally. In the book of Deuteronomy, the fifth book of the Hebrew Bible, God proclaims that if Israel obeys the laws, “the Lord will open for you his bounteous store, the heavens, to provide rain for your land in season.”

Disobedience, however, will have the opposite effect: “The skies above your head shall be copper and the earth under you iron. The Lord will make the rain of your land dust, and sand shall drop on you from the sky, until you are wiped out.”

To ancient Israelites there was no such thing as nature as we understand it today and no such thing as chance. If things were good, it was because God was happy. If things were going badly, it was because the deity was angry. For a national catastrophe like famine, the sin had to lie either with the entire people, or with the monarchs who represented them. And it was the task of prophets and oracles to determine the cause of the divine wrath.

Divine anger…and punishment

Famine was seen as both punishment and opportunity. Suffering opened the door for repentance and change. For example, when the famously wise King Solomon inaugurates the temple in Jerusalem, he prays that God will be forgiving when, in the future, a famine-stricken Israel turns toward the newly built temple for mercy.

The Bible’s association of famine and other natural disasters with divine anger and punishment paved the way for faith leaders throughout the ages to use their pulpits to cast blame on those they found morally wanting. Preachers during the Dust Bowl of 1920s and 1930s America held alcohol and immorality responsible for provoking God’s anger. In 2005, televangelist Pat Robertson blamed abortion for Hurricane Katrina. Today some religious leaders have even assigned responsibility for the coronavirus pandemic to LGBTQ people.

In the book of Samuel, we read that Israel endured a three-year famine in the time of David, considered Israel’s greatest king. When David inquires as to the cause of the famine, he is told that it is due to the sins of his predecessor and mortal enemy, Saul. The story illustrates how biblical authors, like modern moral crusaders, used the opportunity of famine to demonize their opponents.

For the biblical writers interested in legislating and prophesying about Israel’s behavior, famine was both an ending – the result of disobedience and sin – and also a beginning, a potential turning point toward a better, more faithful future.

Other biblical authors, however, focused less on how or why famines happened and more on the opportunities that famine provided for telling new stories.

Seeking refuge

Famine as a narrative device – rather than as a theological tool – is found regularly throughout the Bible. The writers of the Hebrew Bible used famine as the motivating factor for major changes in the lives of its characters – undoubtedly reflecting the reality of famine’s impact in the ancient world.

We see this numerous times in the book of Genesis. For example, famine drives the biblical characters of Abraham to Egypt, Isaac to the land of the Philistines and Jacob and his entire family to Egypt.

Similarly, the book of Ruth opens with a famine that forces Naomi, the mother-in-law of Ruth, and her family to move first to, and then away from, Moab.

An engraving depicts Naomi instructing her daughter-in-law Ruth to leave with Orpah, her other daughter-in-law, from the book of Ruth, in the Old Testament.

The story of Ruth depends on the initial famine; it ends with Ruth being the ancestor of King David. Neither the Exodus nor King David – the central story and the main character of the Hebrew Bible – would exist without famine.

All of these stories share a common feature: famine as an impetus for the movement of people. And with that movement, in the ancient world as today, comes vulnerability. Residing in a foreign land meant abandoning social protections: land and kin, and perhaps even deity. One was at the mercy of the local populace.

This is why Israel, at least, had a wide range of laws intended to protect the stranger. It was understood that famine, or plague, or war, was common enough that anyone might be forced to leave their land to seek refuge in another. The principle of hospitality, still common in the region, ensured that the displaced would be protected.

Famine was a constant threat and a very real part of life for the ancient Israelite world that produced the Hebrew Bible. The ways that the Bible understood and addressed famine, in turn, have had a lasting impact down to the present. Most people today may not see famine as a manifestation of divine wrath. But they might recognize in famine the same opportunities to consider how we treat the displaced, and to imagine a better future

https://currently.att.yahoo.com/news/fa ... 40333.html

Joel Baden, Professor of Hebrew Bible, Yale Divinity School

The Conversation Wed, April 21, 2021, 7:24 AM

As the coronavirus spread rapidly around the world last year, the United Nations warned that the economic disruption of the pandemic could result in famines of “biblical proportions.”

The choice of words conveys more than just scale. Biblical stories of devastating famines are familiar to many. As a scholar of the Hebrew Bible, I understand that famines in biblical times were interpreted as more than mere natural occurrences. The authors of the Hebrew Bible used famine as a mechanism of divine wrath and destruction – but also as a storytelling device, a way to move the narrative forward.

When the heavens don’t open

Underlying the texts about famine in the Hebrew Bible was the constant threat and recurring reality of famine in ancient Israel.

Israel occupied the rocky highlands of Canaan – the area of present-day Jerusalem and the hills to the north of it – rather than fertile coastal plains. Even in the best of years, it took enormous effort to coax sufficient sustenance out of the ground. The rainy seasons were brief; any precipitation less than normal could be devastating.

Across the ancient Near East, drought and famine were feared. In the 13th century B.C., nearly all of the Eastern Mediterranean civilizations collapsed because of a prolonged drought.

For the biblical authors, rain was a blessing and drought a curse – quite literally. In the book of Deuteronomy, the fifth book of the Hebrew Bible, God proclaims that if Israel obeys the laws, “the Lord will open for you his bounteous store, the heavens, to provide rain for your land in season.”

Disobedience, however, will have the opposite effect: “The skies above your head shall be copper and the earth under you iron. The Lord will make the rain of your land dust, and sand shall drop on you from the sky, until you are wiped out.”