SOCIAL TRENDS

China Says It Will Allow Couples to Have 3 Children, Up From 2

The move is the Communist Party’s latest attempt to reverse declining birthrates and avert a population crisis, but experts say it is woefully inadequate.

China said on Monday that it would allow all married couples to have three children, ending a two-child policy that has failed to raise the country’s declining birthrates and avert a demographic crisis.

The announcement by the ruling Communist Party represents an acknowledgment that its limits on reproduction, the world’s toughest, have jeopardized the country’s future. The labor pool is shrinking and the population is graying, threatening the industrial strategy that China has used for decades to emerge from poverty to become an economic powerhouse.

But it is far from clear that relaxing the policy further will pay off. People in China have responded coolly to the party’s earlier move, in 2016, to allow couples to have two children. To them, such measures do little to assuage their anxiety over the rising cost of education and of supporting aging parents, made worse by the lack of day care and the pervasive culture of long work hours.

In a nod to those concerns, the party also indicated on Monday that it would improve maternity leave and workplace protections, pledging to make it easier for couples to have more children. But those protections are all but absent for single mothers in China, who despite the push for more children still lack access to benefits.

Births in China have fallen for four consecutive years, including in 2020, when the number of babies born dropped to the lowest since the Mao era. The country’s total fertility rate — an estimate of the number of children born over a woman’s lifetime — now stands at 1.3, well below the replacement rate of 2.1, raising the possibility of a shrinking population over time.

The announcement on Monday still splits the difference between individual reproductive rights and government limits over women’s bodies. Prominent voices within China have called on the party to scrap its restrictions on births altogether. But Beijing, under Xi Jinping, the party leader who has pushed for greater control in the daily lives of the country’s 1.4 billion people, has resisted.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/31/worl ... 778d3e6de3

The move is the Communist Party’s latest attempt to reverse declining birthrates and avert a population crisis, but experts say it is woefully inadequate.

China said on Monday that it would allow all married couples to have three children, ending a two-child policy that has failed to raise the country’s declining birthrates and avert a demographic crisis.

The announcement by the ruling Communist Party represents an acknowledgment that its limits on reproduction, the world’s toughest, have jeopardized the country’s future. The labor pool is shrinking and the population is graying, threatening the industrial strategy that China has used for decades to emerge from poverty to become an economic powerhouse.

But it is far from clear that relaxing the policy further will pay off. People in China have responded coolly to the party’s earlier move, in 2016, to allow couples to have two children. To them, such measures do little to assuage their anxiety over the rising cost of education and of supporting aging parents, made worse by the lack of day care and the pervasive culture of long work hours.

In a nod to those concerns, the party also indicated on Monday that it would improve maternity leave and workplace protections, pledging to make it easier for couples to have more children. But those protections are all but absent for single mothers in China, who despite the push for more children still lack access to benefits.

Births in China have fallen for four consecutive years, including in 2020, when the number of babies born dropped to the lowest since the Mao era. The country’s total fertility rate — an estimate of the number of children born over a woman’s lifetime — now stands at 1.3, well below the replacement rate of 2.1, raising the possibility of a shrinking population over time.

The announcement on Monday still splits the difference between individual reproductive rights and government limits over women’s bodies. Prominent voices within China have called on the party to scrap its restrictions on births altogether. But Beijing, under Xi Jinping, the party leader who has pushed for greater control in the daily lives of the country’s 1.4 billion people, has resisted.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/31/worl ... 778d3e6de3

Have Three Children? No Way, Many Chinese Say.

Intense workplace competition, inadequate child care and widespread job discrimination against pregnant women have made childbearing an unappealing prospect for many.

After China said it would allow couples to have three children, the state news media trumpeted the move as a major change that would help stimulate growth. But across much of the country, the announcement was met with indignation.

Women worried that the move would only exacerbate discrimination from employers reluctant to pay maternity leave. Young people fumed that they were already hard-pressed to find jobs and take care of themselves, let alone a child (or three). Working-class parents said the financial burden of more children would be unbearable.

“I definitely will not have another child,” said Hu Daifang, a former migrant worker in Sichuan Province. Mr. Hu, 35, said he was already struggling, especially after his mother fell ill and could no longer help care for his two children. “It feels like we are just surviving, not living.”

For many ordinary Chinese, the news about the policy change on Monday was only a reminder of a problem they’d long recognized: the drastic inadequacy of China’s social safety net and legal protections that would enable them to have more children.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/01/worl ... 778d3e6de3

Intense workplace competition, inadequate child care and widespread job discrimination against pregnant women have made childbearing an unappealing prospect for many.

After China said it would allow couples to have three children, the state news media trumpeted the move as a major change that would help stimulate growth. But across much of the country, the announcement was met with indignation.

Women worried that the move would only exacerbate discrimination from employers reluctant to pay maternity leave. Young people fumed that they were already hard-pressed to find jobs and take care of themselves, let alone a child (or three). Working-class parents said the financial burden of more children would be unbearable.

“I definitely will not have another child,” said Hu Daifang, a former migrant worker in Sichuan Province. Mr. Hu, 35, said he was already struggling, especially after his mother fell ill and could no longer help care for his two children. “It feels like we are just surviving, not living.”

For many ordinary Chinese, the news about the policy change on Monday was only a reminder of a problem they’d long recognized: the drastic inadequacy of China’s social safety net and legal protections that would enable them to have more children.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/01/worl ... 778d3e6de3

Why Is It OK to Be Mean to the Ugly?

A manager sits behind a table and decides he’s going to fire a woman because he doesn’t like her skin. If he fires her because her skin is brown, we call that racism and there is legal recourse. If he fires her because her skin is female, we call that sexism and there is legal recourse. If he fires her because her skin is pockmarked and he finds her unattractive, well, we don’t talk about that much and, in most places in America, there is no legal recourse.

This is puzzling. We live in a society that abhors discrimination on the basis of many traits. And yet one of the major forms of discrimination is lookism, prejudice against the unattractive. And this gets almost no attention and sparks little outrage. Why?

Lookism starts, like every form of bigotry, with prejudice and stereotypes.

Studies show that most people consider an “attractive” face to have clean, symmetrical features. We find it easier to recognize and categorize these prototypical faces than we do irregular and “unattractive” ones. So we find it easier — from a brain processing perspective — to look at attractive people.

Attractive people thus start off with a slight physical advantage. But then people project all sorts of widely unrelated stereotypes onto them. In survey after survey, beautiful people are described as trustworthy, competent, friendly, likable and intelligent, while ugly people get the opposite labels. This is a version of the halo effect.

Not all the time, but often, the attractive get the first-class treatment. Research suggests they are more likely to be offered job interviews, more likely to be hired when interviewed and more likely to be promoted than less attractive individuals. They are more likely to receive loans and more likely to receive lower interest rates on those loans.

The discriminatory effects of lookism are pervasive. Attractive economists are more likely to study at high-ranked graduate programs and their papers are cited more often than papers from their less attractive peers. One study found that when unattractive criminals committed a moderate misdemeanor, their fines were about four times as large as those of attractive criminals.

Daniel Hamermesh, a leading scholar in this field, observed that an American worker who is among the bottom one-seventh in looks earns about 10 to 15 percent less a year than one in the top third. An unattractive person misses out on nearly a quarter-million dollars in earnings over a lifetime.

The overall effect of these biases is vast. One 2004 study found that more people report being discriminated against because of their looks than because of their ethnicity.

In a study published in the current issue of the American Journal of Sociology, Ellis P. Monk Jr., Michael H. Esposito and Hedwig Lee report that the earnings gap between people perceived as attractive and unattractive rivals or exceeds the earnings gap between white and Black adults. They find the attractiveness curve is especially punishing for Black women. Those who meet the socially dominant criteria for beauty see an earnings boost; those who don’t earn on average just 63 cents to the dollar of those who do.

Why are we so blasé about this kind of discrimination? Maybe people think lookism is baked into human nature and there’s not much they can do about it. Maybe it’s because there’s no National Association of Ugly People lobbying for change. The economist Tyler Cowen notices that it’s often the educated coastal class that most strictly enforces norms about thinness and dress. Maybe we don’t like policing the bigotry we’re most guilty of?

My general answer is that it’s very hard to buck the core values of your culture, even when you know it’s the right thing to do.

Over the past few decades, social media, the meritocracy and celebrity culture have fused to form a modern culture that is almost pagan in its values. That is, it places tremendous emphasis on competitive display, personal achievement and the idea that physical beauty is an external sign of moral beauty and overall worth.

Pagan culture holds up a certain ideal hero — those who are genetically endowed in the realms of athleticism, intelligence and beauty. This culture looks at obesity as a moral weakness and a sign that you’re in a lower social class.

Our pagan culture places great emphasis on the sports arena, the university and the social media screen, where beauty, strength and I.Q. can be most impressively displayed.

This ethos underlies many athletic shoe and gym ads, which hold up heroes in whom physical endowments and moral goodness are one. It’s the paganism of the C.E.O. who likes to be flanked by a team of hot staffers. (“I must be a winner because I’m surrounded by the beautiful.”) It’s the fashion magazine in which articles about social justice are interspersed with photo spreads of the impossibly beautiful. (“We believe in social equality, as long as you’re gorgeous.”) It’s the lookist one-upmanship of TikTok.

A society that celebrates beauty this obsessively is going to be a social context in which the less beautiful will be slighted. The only solution is to shift the norms and practices. One positive example comes, oddly, from Victoria’s Secret, which replaced its “Angels” with seven women of more diverse body types. When Victoria’s Secret is on the cutting edge of the fight against lookism, the rest of us have some catching up to do.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/24/opin ... 778d3e6de3

A manager sits behind a table and decides he’s going to fire a woman because he doesn’t like her skin. If he fires her because her skin is brown, we call that racism and there is legal recourse. If he fires her because her skin is female, we call that sexism and there is legal recourse. If he fires her because her skin is pockmarked and he finds her unattractive, well, we don’t talk about that much and, in most places in America, there is no legal recourse.

This is puzzling. We live in a society that abhors discrimination on the basis of many traits. And yet one of the major forms of discrimination is lookism, prejudice against the unattractive. And this gets almost no attention and sparks little outrage. Why?

Lookism starts, like every form of bigotry, with prejudice and stereotypes.

Studies show that most people consider an “attractive” face to have clean, symmetrical features. We find it easier to recognize and categorize these prototypical faces than we do irregular and “unattractive” ones. So we find it easier — from a brain processing perspective — to look at attractive people.

Attractive people thus start off with a slight physical advantage. But then people project all sorts of widely unrelated stereotypes onto them. In survey after survey, beautiful people are described as trustworthy, competent, friendly, likable and intelligent, while ugly people get the opposite labels. This is a version of the halo effect.

Not all the time, but often, the attractive get the first-class treatment. Research suggests they are more likely to be offered job interviews, more likely to be hired when interviewed and more likely to be promoted than less attractive individuals. They are more likely to receive loans and more likely to receive lower interest rates on those loans.

The discriminatory effects of lookism are pervasive. Attractive economists are more likely to study at high-ranked graduate programs and their papers are cited more often than papers from their less attractive peers. One study found that when unattractive criminals committed a moderate misdemeanor, their fines were about four times as large as those of attractive criminals.

Daniel Hamermesh, a leading scholar in this field, observed that an American worker who is among the bottom one-seventh in looks earns about 10 to 15 percent less a year than one in the top third. An unattractive person misses out on nearly a quarter-million dollars in earnings over a lifetime.

The overall effect of these biases is vast. One 2004 study found that more people report being discriminated against because of their looks than because of their ethnicity.

In a study published in the current issue of the American Journal of Sociology, Ellis P. Monk Jr., Michael H. Esposito and Hedwig Lee report that the earnings gap between people perceived as attractive and unattractive rivals or exceeds the earnings gap between white and Black adults. They find the attractiveness curve is especially punishing for Black women. Those who meet the socially dominant criteria for beauty see an earnings boost; those who don’t earn on average just 63 cents to the dollar of those who do.

Why are we so blasé about this kind of discrimination? Maybe people think lookism is baked into human nature and there’s not much they can do about it. Maybe it’s because there’s no National Association of Ugly People lobbying for change. The economist Tyler Cowen notices that it’s often the educated coastal class that most strictly enforces norms about thinness and dress. Maybe we don’t like policing the bigotry we’re most guilty of?

My general answer is that it’s very hard to buck the core values of your culture, even when you know it’s the right thing to do.

Over the past few decades, social media, the meritocracy and celebrity culture have fused to form a modern culture that is almost pagan in its values. That is, it places tremendous emphasis on competitive display, personal achievement and the idea that physical beauty is an external sign of moral beauty and overall worth.

Pagan culture holds up a certain ideal hero — those who are genetically endowed in the realms of athleticism, intelligence and beauty. This culture looks at obesity as a moral weakness and a sign that you’re in a lower social class.

Our pagan culture places great emphasis on the sports arena, the university and the social media screen, where beauty, strength and I.Q. can be most impressively displayed.

This ethos underlies many athletic shoe and gym ads, which hold up heroes in whom physical endowments and moral goodness are one. It’s the paganism of the C.E.O. who likes to be flanked by a team of hot staffers. (“I must be a winner because I’m surrounded by the beautiful.”) It’s the fashion magazine in which articles about social justice are interspersed with photo spreads of the impossibly beautiful. (“We believe in social equality, as long as you’re gorgeous.”) It’s the lookist one-upmanship of TikTok.

A society that celebrates beauty this obsessively is going to be a social context in which the less beautiful will be slighted. The only solution is to shift the norms and practices. One positive example comes, oddly, from Victoria’s Secret, which replaced its “Angels” with seven women of more diverse body types. When Victoria’s Secret is on the cutting edge of the fight against lookism, the rest of us have some catching up to do.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/24/opin ... 778d3e6de3

These Chinese Millennials Are ‘Chilling,’ and Beijing Isn’t Happy

Young people in China have set off a nascent counterculture movement that involves lying down and doing as little as possible.

Five years ago, Luo Huazhong discovered that he enjoyed doing nothing. He quit his job as a factory worker in China, biked 1,300 miles from Sichuan Province to Tibet and decided he could get by on odd jobs and $60 a month from his savings. He called his new lifestyle “lying flat.”

“I have been chilling,” Mr. Luo, 31, wrote in a blog post in April, describing his way of life. “I don’t feel like there’s anything wrong.”

He titled his post “Lying Flat Is Justice,” attaching a photo of himself lying on his bed in a dark room with the curtains drawn. Before long, the post was being celebrated by Chinese millennials as an anti-consumerist manifesto. “Lying flat” went viral and has since become a broader statement about Chinese society.

A generation ago, the route to success in China was to work hard, get married and have children. The country’s authoritarianism was seen as a fair trade-off as millions were lifted out of poverty. But with employees working longer hours and housing prices rising faster than incomes, many young Chinese fear they will be the first generation not to do better than their parents.

They are now defying the country’s long-held prosperity narrative by refusing to participate in it.

Mr. Luo’s blog post was removed by censors, who saw it as an affront to Beijing’s economic ambitions. Mentions of “lying flat” — tangping, as it’s known in Mandarin — are heavily restricted on the Chinese internet. An official counternarrative has also emerged, encouraging young people to work hard for the sake of the country’s future.

“After working for so long, I just felt numb, like a machine,” Mr. Luo said in an interview. “And so I resigned.”

To lie flat means to forgo marriage, not have children, stay unemployed and eschew material wants such as a house or a car. It is the opposite of what China’s leaders have asked of their people. But that didn’t bother Leon Ding.

Mr. Ding, 22, has been lying flat for almost three months and thinks of the act as “silent resistance.” He dropped out of a university in his final year in March because he didn’t like the computer science major his parents had chosen for him.

After leaving school, Mr. Ding used his savings to rent a room in Shenzhen. He tried to find a regular office job but realized that most positions required him to work long hours. “I want a stable job that allows me to have my own time to relax, but where can I find it?” he said.

Mr. Ding thinks young people should work hard for what they love, but not “996” — 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week — as many employers in China expect. Frustrated with the job search, he decided that “lying flat” was the way to go.

“To be honest, it feels really comfortable,” he said. “I don’t want to be too hard on myself.”

To make ends meet, Mr. Ding gets paid to play video games and has minimized his spending by doing things like cutting out his favorite bubble tea. Asked about his long-term plans, he said: “Come back and ask me in six months. I only plan for six months.”

While plenty of Chinese millennials continue to adhere to the country’s traditional work ethic, “lying flat” reflects both a nascent counterculture movement and a backlash against China’s hypercompetitive work environment.

Xiang Biao, a professor of social anthropology at Oxford University who focuses on Chinese society, called tangping culture a turning point for China. “Young people feel a kind of pressure that they cannot explain and they feel that promises were broken,” he said. “People realize that material betterment is no longer the single most important source of meaning in life.”

The ruling Communist Party, wary of any form of social instability, has targeted the “lying flat” idea as a threat to stability in China. Censors have deleted a tangping group with more than 9,000 members on Douban, a popular internet forum. The authorities also barred posts on another tangping forum with more than 200,000 members.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/03/worl ... 778d3e6de3

Young people in China have set off a nascent counterculture movement that involves lying down and doing as little as possible.

Five years ago, Luo Huazhong discovered that he enjoyed doing nothing. He quit his job as a factory worker in China, biked 1,300 miles from Sichuan Province to Tibet and decided he could get by on odd jobs and $60 a month from his savings. He called his new lifestyle “lying flat.”

“I have been chilling,” Mr. Luo, 31, wrote in a blog post in April, describing his way of life. “I don’t feel like there’s anything wrong.”

He titled his post “Lying Flat Is Justice,” attaching a photo of himself lying on his bed in a dark room with the curtains drawn. Before long, the post was being celebrated by Chinese millennials as an anti-consumerist manifesto. “Lying flat” went viral and has since become a broader statement about Chinese society.

A generation ago, the route to success in China was to work hard, get married and have children. The country’s authoritarianism was seen as a fair trade-off as millions were lifted out of poverty. But with employees working longer hours and housing prices rising faster than incomes, many young Chinese fear they will be the first generation not to do better than their parents.

They are now defying the country’s long-held prosperity narrative by refusing to participate in it.

Mr. Luo’s blog post was removed by censors, who saw it as an affront to Beijing’s economic ambitions. Mentions of “lying flat” — tangping, as it’s known in Mandarin — are heavily restricted on the Chinese internet. An official counternarrative has also emerged, encouraging young people to work hard for the sake of the country’s future.

“After working for so long, I just felt numb, like a machine,” Mr. Luo said in an interview. “And so I resigned.”

To lie flat means to forgo marriage, not have children, stay unemployed and eschew material wants such as a house or a car. It is the opposite of what China’s leaders have asked of their people. But that didn’t bother Leon Ding.

Mr. Ding, 22, has been lying flat for almost three months and thinks of the act as “silent resistance.” He dropped out of a university in his final year in March because he didn’t like the computer science major his parents had chosen for him.

After leaving school, Mr. Ding used his savings to rent a room in Shenzhen. He tried to find a regular office job but realized that most positions required him to work long hours. “I want a stable job that allows me to have my own time to relax, but where can I find it?” he said.

Mr. Ding thinks young people should work hard for what they love, but not “996” — 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week — as many employers in China expect. Frustrated with the job search, he decided that “lying flat” was the way to go.

“To be honest, it feels really comfortable,” he said. “I don’t want to be too hard on myself.”

To make ends meet, Mr. Ding gets paid to play video games and has minimized his spending by doing things like cutting out his favorite bubble tea. Asked about his long-term plans, he said: “Come back and ask me in six months. I only plan for six months.”

While plenty of Chinese millennials continue to adhere to the country’s traditional work ethic, “lying flat” reflects both a nascent counterculture movement and a backlash against China’s hypercompetitive work environment.

Xiang Biao, a professor of social anthropology at Oxford University who focuses on Chinese society, called tangping culture a turning point for China. “Young people feel a kind of pressure that they cannot explain and they feel that promises were broken,” he said. “People realize that material betterment is no longer the single most important source of meaning in life.”

The ruling Communist Party, wary of any form of social instability, has targeted the “lying flat” idea as a threat to stability in China. Censors have deleted a tangping group with more than 9,000 members on Douban, a popular internet forum. The authorities also barred posts on another tangping forum with more than 200,000 members.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/03/worl ... 778d3e6de3

She’s One of China’s Biggest Stars. She’s Also Transgender.

Jin Xing, the first person in China to openly undergo transition surgery, is a household name. But she says she’s no standard-bearer for the L.G.B.T.Q. community.

Jin Xing, a 53-year-old television host often called China’s Oprah Winfrey, holds strong views about what it means to be a woman. She has hounded female guests to hurry up and get married, and she has pressed others to give birth. When it comes to men, she has recommended that women act helpless to get their way.

That might not be so unusual in China, where traditional gender norms are still deeply embedded, especially among older people. Except Ms. Jin is no typical Chinese star.

As China’s first — and even today, only — major transgender celebrity, Ms. Jin is in many ways regarded as a progressive icon. She underwent transition surgery in 1995, the first person in the country to do so openly. She went on to host one of China’s most popular talk shows, even as stigmas against L.G.B.T.Q. people remained — and still remain — widespread.

China’s best-known personalities appeared on her program, “The Jin Xing Show.” Brad Pitt once bumbled through some Mandarin with her to promote a film.

“All my close friends teased me: ‘China would never let you host a talk show,’” Ms. Jin said, recalling when she first shared that goal with them. “‘How could they let you, with your transgender identity, be on television?’”

But even as Ms. Jin’s remarkable biography has elevated her to an almost mythic level, it has also, for some, made her one of the most perplexing figures in Chinese pop culture.

Though often lauded as a trailblazer for the L.G.B.T.Q. community, she rejects the role of standard-bearer and criticizes activists whom she perceives as seeking special treatment. “Respect is earned by yourself, not something you ask society to give you,” she said.

She also has attracted fierce criticism for her views on womanhood. In a 2013 memoir, Ms. Jin wrote that a “smart woman” should make her partner feel that she was a “little girl who needs him.” On “The Jin Xing Show,” she told the actress Michelle Ye that only after giving birth would she feel complete.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/16/worl ... 778d3e6de3

Jin Xing, the first person in China to openly undergo transition surgery, is a household name. But she says she’s no standard-bearer for the L.G.B.T.Q. community.

Jin Xing, a 53-year-old television host often called China’s Oprah Winfrey, holds strong views about what it means to be a woman. She has hounded female guests to hurry up and get married, and she has pressed others to give birth. When it comes to men, she has recommended that women act helpless to get their way.

That might not be so unusual in China, where traditional gender norms are still deeply embedded, especially among older people. Except Ms. Jin is no typical Chinese star.

As China’s first — and even today, only — major transgender celebrity, Ms. Jin is in many ways regarded as a progressive icon. She underwent transition surgery in 1995, the first person in the country to do so openly. She went on to host one of China’s most popular talk shows, even as stigmas against L.G.B.T.Q. people remained — and still remain — widespread.

China’s best-known personalities appeared on her program, “The Jin Xing Show.” Brad Pitt once bumbled through some Mandarin with her to promote a film.

“All my close friends teased me: ‘China would never let you host a talk show,’” Ms. Jin said, recalling when she first shared that goal with them. “‘How could they let you, with your transgender identity, be on television?’”

But even as Ms. Jin’s remarkable biography has elevated her to an almost mythic level, it has also, for some, made her one of the most perplexing figures in Chinese pop culture.

Though often lauded as a trailblazer for the L.G.B.T.Q. community, she rejects the role of standard-bearer and criticizes activists whom she perceives as seeking special treatment. “Respect is earned by yourself, not something you ask society to give you,” she said.

She also has attracted fierce criticism for her views on womanhood. In a 2013 memoir, Ms. Jin wrote that a “smart woman” should make her partner feel that she was a “little girl who needs him.” On “The Jin Xing Show,” she told the actress Michelle Ye that only after giving birth would she feel complete.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/16/worl ... 778d3e6de3

What’s Ripping American Families Apart?

At least 27 percent of Americans are estranged from a member of their own family, and research suggests about 40 percent of Americans have experienced estrangement at some point.

The most common form of estrangement is between adult children and one or both parents — a cut usually initiated by the child. A study published in 2010 found that parents in the U.S. are about twice as likely to be in a contentious relationship with their adult children as parents in Israel, Germany, England and Spain.

The Cornell sociologist Karl Pillemer, author of “Fault Lines: Fractured Families and How to Mend Them,” writes that the children in these cases often cite harsh parenting, parental favoritism, divorce and poor and increasingly hostile communication often culminating in a volcanic event. As one woman told Salon: “I have someone out to get me, and it’s my mother. My part of being a good mom has been getting my son away from mine.”

The parents in these cases are often completely bewildered by the accusations. They often remember a totally different childhood home and accuse their children of rewriting what happened. As one cutoff couple told the psychologist Joshua Coleman: “Emotional abuse? We gave our child everything. We read every parenting book under the sun, took her on wonderful vacations, went to all of her sporting events.”

Part of the misunderstanding derives from the truth that we all construct our own realities, but part of the problem, as Nick Haslam of the University of Melbourne has suggested, is there seems to be a generational shift in what constitutes abuse. Practices that seemed like normal parenting to one generation are conceptualized as abusive, overbearing and traumatizing to another.

There’s a lot of real emotional abuse out there, but as Coleman put it in an essay in The Atlantic, “My recent research — and my clinical work over the past four decades — has shown me that you can be a conscientious parent and your kid may still want nothing to do with you when they’re older.”

Either way, there’s a lot of agony for all concerned. The children feel they have to live with the legacy of an abusive childhood. The parents feel rejected by the person they love most in the world, their own child, and they are powerless to do anything about it. There’s anger, grief and depression on all sides — painful holidays and birthdays — plus, the next generation often grows up without knowing their grandparents.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/29/opin ... 778d3e6de3

At least 27 percent of Americans are estranged from a member of their own family, and research suggests about 40 percent of Americans have experienced estrangement at some point.

The most common form of estrangement is between adult children and one or both parents — a cut usually initiated by the child. A study published in 2010 found that parents in the U.S. are about twice as likely to be in a contentious relationship with their adult children as parents in Israel, Germany, England and Spain.

The Cornell sociologist Karl Pillemer, author of “Fault Lines: Fractured Families and How to Mend Them,” writes that the children in these cases often cite harsh parenting, parental favoritism, divorce and poor and increasingly hostile communication often culminating in a volcanic event. As one woman told Salon: “I have someone out to get me, and it’s my mother. My part of being a good mom has been getting my son away from mine.”

The parents in these cases are often completely bewildered by the accusations. They often remember a totally different childhood home and accuse their children of rewriting what happened. As one cutoff couple told the psychologist Joshua Coleman: “Emotional abuse? We gave our child everything. We read every parenting book under the sun, took her on wonderful vacations, went to all of her sporting events.”

Part of the misunderstanding derives from the truth that we all construct our own realities, but part of the problem, as Nick Haslam of the University of Melbourne has suggested, is there seems to be a generational shift in what constitutes abuse. Practices that seemed like normal parenting to one generation are conceptualized as abusive, overbearing and traumatizing to another.

There’s a lot of real emotional abuse out there, but as Coleman put it in an essay in The Atlantic, “My recent research — and my clinical work over the past four decades — has shown me that you can be a conscientious parent and your kid may still want nothing to do with you when they’re older.”

Either way, there’s a lot of agony for all concerned. The children feel they have to live with the legacy of an abusive childhood. The parents feel rejected by the person they love most in the world, their own child, and they are powerless to do anything about it. There’s anger, grief and depression on all sides — painful holidays and birthdays — plus, the next generation often grows up without knowing their grandparents.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/29/opin ... 778d3e6de3

The Married Will Soon Be the Minority

When I was young, everything in society seemed to aim one toward marriage. It was the expectation. It was the inevitability. You would — and should — meet someone, get married and start a family. It was the way it had always been, and always would be.

But even then, the share of people who were married was already falling. The year I was born, 1970, the percentage of Americans between the ages of 25 and 50 who had never married was just 9 percent. By the time I became an adult, that number was approaching 20 percent.

Some people were delaying marriage. But others were forgoing it altogether.

This trend has only continued, and we are now nearing a milestone. This month, the Pew Research Center published an analysis of census data showing that in 2019 the share of American adults who were neither married nor living with a partner had risen to 38 percent, and while that group “includes some adults who were previously married (those who are separated, divorced or widowed), all of the growth in the unpartnered population since 1990 has come from a rise in the number who have never been married.”

This came on the heels of data released by the National Center for Health Statistics last year, which showed that marriage rates in 2018 had reached a record low.

We are nearing a time when there will be more unmarried adults in the United States than married ones, a development with enormous consequences for how we define family and adulthood in general, as well as how we structure taxation and benefits.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/20/opin ... 778d3e6de3

When I was young, everything in society seemed to aim one toward marriage. It was the expectation. It was the inevitability. You would — and should — meet someone, get married and start a family. It was the way it had always been, and always would be.

But even then, the share of people who were married was already falling. The year I was born, 1970, the percentage of Americans between the ages of 25 and 50 who had never married was just 9 percent. By the time I became an adult, that number was approaching 20 percent.

Some people were delaying marriage. But others were forgoing it altogether.

This trend has only continued, and we are now nearing a milestone. This month, the Pew Research Center published an analysis of census data showing that in 2019 the share of American adults who were neither married nor living with a partner had risen to 38 percent, and while that group “includes some adults who were previously married (those who are separated, divorced or widowed), all of the growth in the unpartnered population since 1990 has come from a rise in the number who have never been married.”

This came on the heels of data released by the National Center for Health Statistics last year, which showed that marriage rates in 2018 had reached a record low.

We are nearing a time when there will be more unmarried adults in the United States than married ones, a development with enormous consequences for how we define family and adulthood in general, as well as how we structure taxation and benefits.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/20/opin ... 778d3e6de3

International Men’s Day

International Men’s Day: What is it and why does it matter?

There have been calls for an International Men’s Day since the 1960’s and in this era of empowering gender equality, you may have even thought to yourself “Why do women have an international celebration and not men?” or “Men’s contributions and concerns deserve a day of recognition in their own right” and not merely creating an equivalent of International Women’s Day.

Following a series of small events in individual countries in the US, Europe and Australia, International Men’s Day (IMD) was initiated on 1991 and revived on 19th November 1999 in Trinidad and Tobago by history lecturer Dr. Jerome Teelucksingh. The Caribbean initiative is now an annual international event celebrated in over 70 countries with rapidly increasing interest.

International Men’s Day encourages men to teach the boys in their lives the values, character and responsibilities of being a man. It is only when we all, both men and women, lead by example that we will create a fair and safe society which allows everyone the opportunity to prosper.

There are six specific objectives of International Men’s Day:

1. To promote positive male role models; who are living decent and honest lives, not just movie stars and sports men but everyday men

2. To celebrate men's positive contributions to society, community, family, marriage, child care, and to the environment

3. To focus on men's health and wellbeing; social, emotional, physical and spiritual

4. To highlight discrimination against men; in areas of social services, social attitudes and expectations, and law

5. To improve gender relations and promote gender equality

6. To create a safer, better world; where people can be safe and grow to reach their full potential

"The concept and themes of IMD are designed to give hope to the depressed, faith to the lonely, comfort to the broken-hearted, transcend barriers, eliminate stereotypes and create a more caring humanity.” - Dr. Jerome Teelucksingh

There are many inspiring men leading by example in our community and we are fortunate to have a diverse set of role models for the Ismaili youth to emulate. Yet some of the national statistics around Gender Equality are distressing. They prove that the perceptions and attitudes in the wider societies in which we live still have a long way to go to overturn negative gender stereotypes.

At the recent Preparing for Parenthood workshop run by WAP, we discussed that only around 1% of eligible fathers in the UK took Shared Parental Leave and that it can still be perceived as strange for men to be involved with childcare. Anecdotes arose about adults at kids events or appointments casually questioning "Where's Mum?" or the hesitation husbands may feel taking time away from work when a man’s role is expected to be the “sole breadwinner” of the household.

Equally concerning is that studies show men are less likely to acknowledge illness or to seek help when sick. Men aged 20-40 are half as likely to go to their GP as women of the same age and are even less likely to be honest about their symptoms when they do go. The figures are even lower for the likelihood of men to seek help for concerns related to their mental health. A message sometimes heard by young boys is “real men sort out their own problems” which holds them back from accepting the emotional or physical support they need and often from aspiring to be role models themselves.

Communities need to build awareness and create safe environments for every individual to feel empowered to make their own choices in prioritising their family, work, health and wellbeing, rather than simply allowing gender stereotypes to take control.

Our leading example, Mowlana Hazar Imam said in a discussion with Harvard University Professor Diana L. Eck on November 12, 2015:

“Leadership qualities is not gender driven so actually, if you don’t respect the fact that both genders have competencies, outstanding capabilities, you are damaging your community by not appointing those people.”

As we reflect on the themes of International Men’s Day, let us think about how we can enable our community to continue to grow and reach its full potential. Let us respect, support and celebrate all men, women and children as we redefine social stereotypes for the benefit of ourselves and our future generations.

References and further information:

www.internationalmensday.com

www.menshealthforum.org.uk

www.sharedparentalleave.campaign.gov.uk

https://the.ismaili/uk/institutions/wom ... l-mens-day

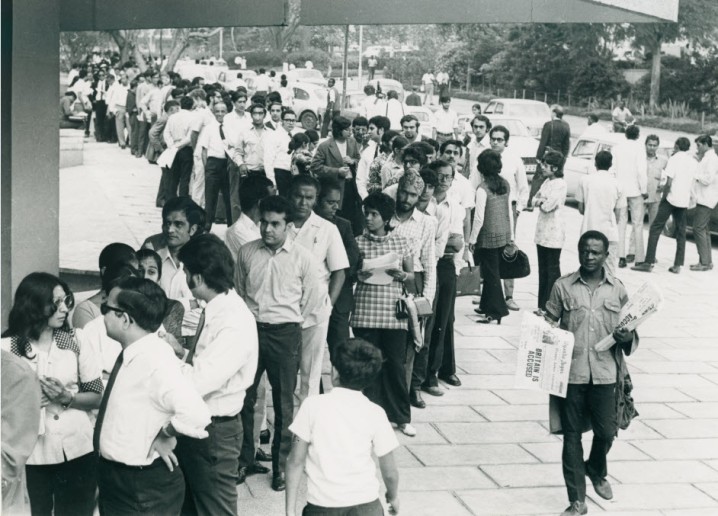

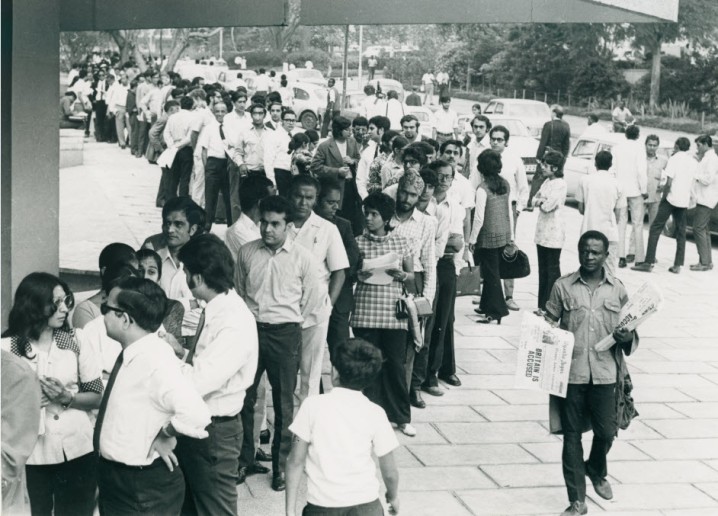

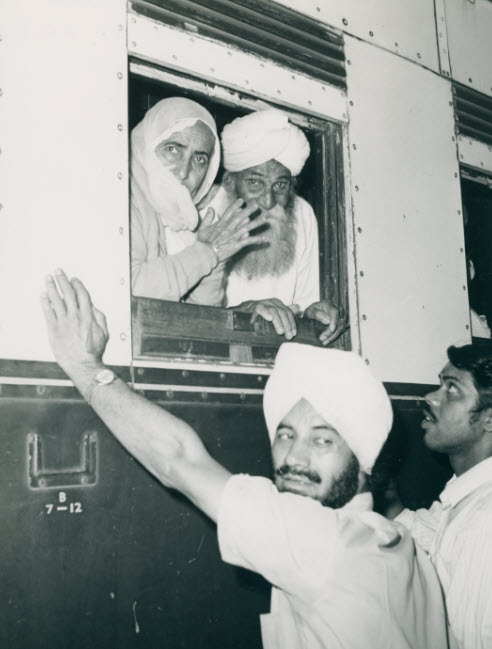

Contending With the Pandemic, Wealthy Nations Wage Global Battle for Migrants

Covid kept many people in place. Now several developed countries, facing aging labor forces and worker shortages, are racing to recruit, train and integrate foreigners.

As the global economy heats up and tries to put the pandemic aside, a battle for the young and able has begun. With fast-track visas and promises of permanent residency, many of the wealthy nations driving the recovery are sending a message to skilled immigrants all over the world: Help wanted. Now.

In Germany, where officials recently warned that the country needs 400,000 new immigrants a year to fill jobs in fields ranging from academia to air-conditioning, a new Immigration Act offers accelerated work visas and six months to visit and find a job.

Canada plans to give residency to 1.2 million new immigrants by 2023. Israel recently finalized a deal to bring health care workers from Nepal. And in Australia, where mines, hospitals and pubs are all short-handed after nearly two years with a closed border, the government intends to roughly double the number of immigrants it allows into the country over the next year.

The global drive to attract foreigners with skills, especially those that fall somewhere between physical labor and a physics Ph.D., aims to smooth out a bumpy emergence from the pandemic.

Covid’s disruptions have pushed many people to retire, resign or just not return to work. But its effects run deeper. By keeping so many people in place, the pandemic has made humanity’s demographic imbalance more obvious — rapidly aging rich nations produce too few new workers, while countries with a surplus of young people often lack work for all.

New approaches to that mismatch could influence the worldwide debate over immigration. European governments remain divided on how to handle new waves of asylum seekers. In the United States, immigration policy remains mostly stuck in place, with a focus on the Mexican border, where migrant detentions have reached a record high. Still, many developed nations are building more generous, efficient and sophisticated programs to bring in foreigners and help them become a permanent part of their societies.

“Covid is an accelerator of change,” said Jean-Christophe Dumont, the head of international migration research for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or O.E.C.D. “Countries have had to realize the importance of migration and immigrants.”

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/23/worl ... ews_dedupe

Covid kept many people in place. Now several developed countries, facing aging labor forces and worker shortages, are racing to recruit, train and integrate foreigners.

As the global economy heats up and tries to put the pandemic aside, a battle for the young and able has begun. With fast-track visas and promises of permanent residency, many of the wealthy nations driving the recovery are sending a message to skilled immigrants all over the world: Help wanted. Now.

In Germany, where officials recently warned that the country needs 400,000 new immigrants a year to fill jobs in fields ranging from academia to air-conditioning, a new Immigration Act offers accelerated work visas and six months to visit and find a job.

Canada plans to give residency to 1.2 million new immigrants by 2023. Israel recently finalized a deal to bring health care workers from Nepal. And in Australia, where mines, hospitals and pubs are all short-handed after nearly two years with a closed border, the government intends to roughly double the number of immigrants it allows into the country over the next year.

The global drive to attract foreigners with skills, especially those that fall somewhere between physical labor and a physics Ph.D., aims to smooth out a bumpy emergence from the pandemic.

Covid’s disruptions have pushed many people to retire, resign or just not return to work. But its effects run deeper. By keeping so many people in place, the pandemic has made humanity’s demographic imbalance more obvious — rapidly aging rich nations produce too few new workers, while countries with a surplus of young people often lack work for all.

New approaches to that mismatch could influence the worldwide debate over immigration. European governments remain divided on how to handle new waves of asylum seekers. In the United States, immigration policy remains mostly stuck in place, with a focus on the Mexican border, where migrant detentions have reached a record high. Still, many developed nations are building more generous, efficient and sophisticated programs to bring in foreigners and help them become a permanent part of their societies.

“Covid is an accelerator of change,” said Jean-Christophe Dumont, the head of international migration research for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, or O.E.C.D. “Countries have had to realize the importance of migration and immigrants.”

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/23/worl ... ews_dedupe

Violence against women insults God, pope says in New Year's message

Reuters Published January 1, 2022 -

Pope Francis celebrates Mass to mark the World Day of Peace in St Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, January 1. Reuters

Pope Francis used his New Year's message on Saturday to issue a clarion call for an end to violence against women, saying it was insulting to God.

Francis, 85, celebrated a Mass in St Peter's Basilica on the day the Roman Catholic Church marks both the solemnity of Holy Mary Mother of God as well as its annual World Day of Peace.

Francis appeared to be in good form on Saturday following an unexplained incident on New Year's Eve where he attended a service but at the last minute did not preside over it as he had been expected to.

At the start of the Mass on Saturday, he walked the entire length of the central aisle of basilica, as opposed to Friday night, when he emerged from a side entrance close to the altar and watched from the sidelines.

Francis suffers from a sciatica condition that causes pain in the legs, and sometimes a flare-up prevents him from standing for long periods.

Francis wove his New Year's homily around the themes of motherhood and women — saying it was they who kept the threads of life together — and used it to make one of his strongest calls yet for an end to violence against them.

"And since mothers bestow life, and women keep the world [together], let us all make greater efforts to promote mothers and to protect women," Francis said.

"How much violence is directed against women! Enough! To hurt a woman is to insult God, who from a woman took on our humanity — not through an angel, not directly, but through a woman," he said, in a reference to Jesus's mother Mary.

During an Italian television programme last month, Francis told a woman who had been beaten by her ex-husband that men who commit violence against women engage in something that is "almost satanic".

Since the Covid-19 pandemic began nearly two years ago, Francis has several times spoken out against domestic violence, which has increased in many countries since lockdowns left many women trapped with their abusers.

Public participation at the Mass was lower than in some past years because of Covid restrictions. Italy, which surrounds Vatican City, reported a record 144,243 coronavirus related cases on Friday and has recently imposed new measures such as an obligation to wear masks outdoors.

In the text of his Message for the World Day of Peace, issued last month, Francis said nations should divert money spent on armaments to invest in education and decried growing military costs at the expense of social services.

The annual peace message is sent to heads of state and international organisations, and the pope gives a signed copy to leaders who make official visits to him at the Vatican during the upcoming year.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1667033/viole ... rs-message

Reuters Published January 1, 2022 -

Pope Francis celebrates Mass to mark the World Day of Peace in St Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, January 1. Reuters

Pope Francis used his New Year's message on Saturday to issue a clarion call for an end to violence against women, saying it was insulting to God.

Francis, 85, celebrated a Mass in St Peter's Basilica on the day the Roman Catholic Church marks both the solemnity of Holy Mary Mother of God as well as its annual World Day of Peace.

Francis appeared to be in good form on Saturday following an unexplained incident on New Year's Eve where he attended a service but at the last minute did not preside over it as he had been expected to.

At the start of the Mass on Saturday, he walked the entire length of the central aisle of basilica, as opposed to Friday night, when he emerged from a side entrance close to the altar and watched from the sidelines.

Francis suffers from a sciatica condition that causes pain in the legs, and sometimes a flare-up prevents him from standing for long periods.

Francis wove his New Year's homily around the themes of motherhood and women — saying it was they who kept the threads of life together — and used it to make one of his strongest calls yet for an end to violence against them.

"And since mothers bestow life, and women keep the world [together], let us all make greater efforts to promote mothers and to protect women," Francis said.

"How much violence is directed against women! Enough! To hurt a woman is to insult God, who from a woman took on our humanity — not through an angel, not directly, but through a woman," he said, in a reference to Jesus's mother Mary.

During an Italian television programme last month, Francis told a woman who had been beaten by her ex-husband that men who commit violence against women engage in something that is "almost satanic".

Since the Covid-19 pandemic began nearly two years ago, Francis has several times spoken out against domestic violence, which has increased in many countries since lockdowns left many women trapped with their abusers.

Public participation at the Mass was lower than in some past years because of Covid restrictions. Italy, which surrounds Vatican City, reported a record 144,243 coronavirus related cases on Friday and has recently imposed new measures such as an obligation to wear masks outdoors.

In the text of his Message for the World Day of Peace, issued last month, Francis said nations should divert money spent on armaments to invest in education and decried growing military costs at the expense of social services.

The annual peace message is sent to heads of state and international organisations, and the pope gives a signed copy to leaders who make official visits to him at the Vatican during the upcoming year.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1667033/viole ... rs-message

The Taliban ordered shop mannequin beheadings, saying the dummies are 'idols' and are forbidden by Islam, reports say

The Taliban ordered shop mannequin beheadings, saying the dummies are 'idols' and are forbidden by Islam, reports say

Joshua Zitser

Sun, January 2, 2022, 5:40 AM

Female mannequins in a shop window in Kabul, Afghanistan

Female mannequins are seen in a shop window in Kabul, Afghanistan. One is headless, while the other two have their faces covered.Marco Di Lauro/Getty Images

Mannequins in Herat, Afghanistan, must have their heads removed, the Taliban has ruled.

The mannequins were being worshipped as idols, claimed the Taliban.

Those who ignore the beheading order face severe punishments, according to The Times.

The Taliban ordered a series of mannequin beheadings, describing the heads of dummies as "idols" that are forbidden by Islam, according to reports.

Shopkeepers in the western Afghan province of Herat were told to remove the heads of female mannequins by The Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice this week, The Times reported.

Those who ignore the order face severe punishments, warned the local department of the ministry, per the media outlet.

Ministers believed that people were worshipping the mannequins as idols, according to MailOnline, and the Quran considers idolatry to be an unforgivable sin.

According to the Aghan media outlet Raha Press, the director of the local ministry said that even looking at the face of a female mannequin is against Sharia law.

An initial order called for the removal of mannequins completely, but a compromise on just removing the heads was agreed, MailOnline said.

Raha Press reported that shopkeepers in Herat are dismayed by the beheading order, citing how expensive the mannequins are. One shopkeeper said mannequins cost up to $200 each, per the news outlet, and added that cutting their heads off is a "great loss" for him.

The Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice in Afghanistan was reinstated in September, after the fall of Kabul. The all-male ministry replaced the former Ministry of Women Affairs, stoking fears that the Taliban's moral police would decimate women's rights in the country.

This week, Sky News reported that the ministry told taxi drivers they should not take women on long journeys if they do not have a male chaperone.

https://currently.att.yahoo.com/news/ta ... 41443.html

The Taliban ordered shop mannequin beheadings, saying the dummies are 'idols' and are forbidden by Islam, reports say

Joshua Zitser

Sun, January 2, 2022, 5:40 AM

Female mannequins in a shop window in Kabul, Afghanistan

Female mannequins are seen in a shop window in Kabul, Afghanistan. One is headless, while the other two have their faces covered.Marco Di Lauro/Getty Images

Mannequins in Herat, Afghanistan, must have their heads removed, the Taliban has ruled.

The mannequins were being worshipped as idols, claimed the Taliban.

Those who ignore the beheading order face severe punishments, according to The Times.

The Taliban ordered a series of mannequin beheadings, describing the heads of dummies as "idols" that are forbidden by Islam, according to reports.

Shopkeepers in the western Afghan province of Herat were told to remove the heads of female mannequins by The Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice this week, The Times reported.

Those who ignore the order face severe punishments, warned the local department of the ministry, per the media outlet.

Ministers believed that people were worshipping the mannequins as idols, according to MailOnline, and the Quran considers idolatry to be an unforgivable sin.

According to the Aghan media outlet Raha Press, the director of the local ministry said that even looking at the face of a female mannequin is against Sharia law.

An initial order called for the removal of mannequins completely, but a compromise on just removing the heads was agreed, MailOnline said.

Raha Press reported that shopkeepers in Herat are dismayed by the beheading order, citing how expensive the mannequins are. One shopkeeper said mannequins cost up to $200 each, per the news outlet, and added that cutting their heads off is a "great loss" for him.

The Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice in Afghanistan was reinstated in September, after the fall of Kabul. The all-male ministry replaced the former Ministry of Women Affairs, stoking fears that the Taliban's moral police would decimate women's rights in the country.

This week, Sky News reported that the ministry told taxi drivers they should not take women on long journeys if they do not have a male chaperone.

https://currently.att.yahoo.com/news/ta ... 41443.html

What Does Marriage Ask Us to Give Up?

I spent most of my 20s and 30s single, only to marry and then come to the conclusion that my marriage should end. Now I am single again. But I am not alone. My marriage ended during the pandemic, while I was at home with family. Since the pandemic began, my daughter and I have been living in what my family jokingly calls “the compound” — a house my mother and I bought together before I was married. She and my siblings and their families live there, in an attempt to withstand the waves of gentrification that have displaced everyone in my family every four to five years, as the sketchy neighborhoods we can afford get “discovered” by rich young people.

The compound is a noisy place. Sometimes, when everyone is talking and laughing and joking at once, my daughter, who is young enough that language is still new to her, will raise her voice in a keening screech to try to join in the cacophony. Living with all this noise has stirred up many emotions: gratitude to my family for their support, the irritation of adolescence as we sometimes catch ourselves in the dances of our older selves; a longing for sleep that can only be felt in a household full of children who are all awake and ready to play by 6:30 a.m. on a Saturday.

What has not materialized is the intense loneliness that people warned me would come with divorce. It was always interesting, telling people about the divorce. Some friends with small children almost panicked about what would come, about how the separation was too rash. But I am lucky in that most of my friends have lived lives falling in and out of partnerships. “You can go it alone, you know” was the much more common response.

We are living through a time when all the stories the larger culture tells us about ourselves are being rewritten: the story of what the United States is; what it means to be a man or a woman; what it means to be a child; what it means to love oneself or other people. We are imagining all of this again so that these stories can guide and comfort us rather than control us.

It’s a different world from the one my parents inhabited when they divorced, one in which many people treated their separation as if it were an infectious disease and shunned us for a number of years. There was the way people spoke to me when they thought my parents were married and the way the tone shifted when they figured out my mother was now alone. A distinct refrain, when growing up: “It’s really just your mother and you all?”

Even as a child, I bristled at the assumptions behind that question. It seemed obvious to me then, having lived in a two-parent home that was deeply unhappy and dysfunctional, that the number of parents around to make a working family was arbitrary, that people beholden to the rigid mathematics of mother and father and children equals stability were shortsighted, ignoring all we know of human interactions and ways we make family throughout human history. To believe that one equation would work for us all seemed so simplistic and childish that for much of my young adulthood, I simply disregarded it.

But the cultural myths around coupledom are hard to resist. It was easy, in childhood, to simply decide there must be another way. It was harder, in adulthood, after years spent marinating in so many cultural stories about what marriage could promise — legitimacy, maturity, stability, strength — to resist that programming. Marriage, of course, can be all those things to many people, but my own brought something different, which has led to this desire to be alone again.

There is a lot of hand wringing currently about the decline of marriage in America. No matter that divorce rates have also gone down, and that when people are marrying, it is at later ages. Our culture may have changed to allow other ways for people to chart their lives, but whole industries and institutions — banking, real estate, health care, insurance, advertising and most important, taxation — revolve around assumptions of marriage as the norm. Without that base assumption, the logic of many of those transactions is thrown out.

It can feel daunting to come up with new narratives about what it means to mature — to be worthy of housing and financial stability and health care, to find companionship or emotional support — when these industries have so much invested, both financially and ideologically, in a particular way of measuring life and community.

In search of new narratives, I have found myself drawn to Diane di Prima’s 2001 memoir, “Recollections of My Life as a Woman.” It focuses on her childhood and life in New York — a portrait of the artist as a young woman, in all her romantic and intuitive glory. Ms. di Prima is remarkable because as a poet in her early 20s in 1950s New York, she decided she wanted to be a mother, and a single mother at that.

“I was a poet,” she wrote, continuing, “There was nothing that I could possibly experience, as a human in a female body, that I would not experience …. There should, it seemed to me, be no quarrel between these two aims: to have a baby and to be a poet.” Nevertheless, she continued, “A conflict held me fast.”

Her memoir revolves around this conflict between motherhood and the demands of an artist. At a certain point, overwhelmed by the demands of parenting children alone while running a press, founding an avant-garde theater, protecting her left-wing friends from raids by the F.B.I. and the grinding poverty of an artist’s life in New York City, Ms. di Prima entered into a marriage of convenience with a man she distrusted. He was the ex-boyfriend of her male best friend. Besides its messy origins, this relationship resembles the dream I’ve heard so many straight women describe, in a joking, not joking way — wishing to start a family with a friend, to avoid the complications of romantic love.

But Ms. di Prima is honest about the limitations of the arrangement. She wrote that she avoided the pains of romance, but the man she married is still a domineering, abusive mess, in her recounting. Furthermore, in marriage, she has lost something integral to herself. “One of my most precious and valued possessions was my independence: my struggle for control over my own life,” she wrote, continuing, “I didn’t see that it had no intrinsic value for anyone but myself, that it was a coin that was precious only within the realm, a currency that could not cross borders.”

These words, when I read them, sounded in me like the chime of a tuning fork. I had never before read such a precise description of what marriage asks some people to give up. Those who panic over the rise in the number of single Americans do not see that this statistic includes lives of hard-won independence — lives that still intersect with a community, with a home, with a belief in something wider than oneself. The people clinging to old narratives around singledom and marriage can’t yet see these lives for what they are because, as Ms. di Prima puts it, they are not “an objectively valuable commodity.” Their meaning is “a currency that cannot cross borders.”

These lives threaten the communal narratives currently in place. But what is a threat to some can be to others a glimmer of a new world coming.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/04/opin ... 778d3e6de3

I spent most of my 20s and 30s single, only to marry and then come to the conclusion that my marriage should end. Now I am single again. But I am not alone. My marriage ended during the pandemic, while I was at home with family. Since the pandemic began, my daughter and I have been living in what my family jokingly calls “the compound” — a house my mother and I bought together before I was married. She and my siblings and their families live there, in an attempt to withstand the waves of gentrification that have displaced everyone in my family every four to five years, as the sketchy neighborhoods we can afford get “discovered” by rich young people.

The compound is a noisy place. Sometimes, when everyone is talking and laughing and joking at once, my daughter, who is young enough that language is still new to her, will raise her voice in a keening screech to try to join in the cacophony. Living with all this noise has stirred up many emotions: gratitude to my family for their support, the irritation of adolescence as we sometimes catch ourselves in the dances of our older selves; a longing for sleep that can only be felt in a household full of children who are all awake and ready to play by 6:30 a.m. on a Saturday.

What has not materialized is the intense loneliness that people warned me would come with divorce. It was always interesting, telling people about the divorce. Some friends with small children almost panicked about what would come, about how the separation was too rash. But I am lucky in that most of my friends have lived lives falling in and out of partnerships. “You can go it alone, you know” was the much more common response.

We are living through a time when all the stories the larger culture tells us about ourselves are being rewritten: the story of what the United States is; what it means to be a man or a woman; what it means to be a child; what it means to love oneself or other people. We are imagining all of this again so that these stories can guide and comfort us rather than control us.

It’s a different world from the one my parents inhabited when they divorced, one in which many people treated their separation as if it were an infectious disease and shunned us for a number of years. There was the way people spoke to me when they thought my parents were married and the way the tone shifted when they figured out my mother was now alone. A distinct refrain, when growing up: “It’s really just your mother and you all?”

Even as a child, I bristled at the assumptions behind that question. It seemed obvious to me then, having lived in a two-parent home that was deeply unhappy and dysfunctional, that the number of parents around to make a working family was arbitrary, that people beholden to the rigid mathematics of mother and father and children equals stability were shortsighted, ignoring all we know of human interactions and ways we make family throughout human history. To believe that one equation would work for us all seemed so simplistic and childish that for much of my young adulthood, I simply disregarded it.

But the cultural myths around coupledom are hard to resist. It was easy, in childhood, to simply decide there must be another way. It was harder, in adulthood, after years spent marinating in so many cultural stories about what marriage could promise — legitimacy, maturity, stability, strength — to resist that programming. Marriage, of course, can be all those things to many people, but my own brought something different, which has led to this desire to be alone again.

There is a lot of hand wringing currently about the decline of marriage in America. No matter that divorce rates have also gone down, and that when people are marrying, it is at later ages. Our culture may have changed to allow other ways for people to chart their lives, but whole industries and institutions — banking, real estate, health care, insurance, advertising and most important, taxation — revolve around assumptions of marriage as the norm. Without that base assumption, the logic of many of those transactions is thrown out.

It can feel daunting to come up with new narratives about what it means to mature — to be worthy of housing and financial stability and health care, to find companionship or emotional support — when these industries have so much invested, both financially and ideologically, in a particular way of measuring life and community.

In search of new narratives, I have found myself drawn to Diane di Prima’s 2001 memoir, “Recollections of My Life as a Woman.” It focuses on her childhood and life in New York — a portrait of the artist as a young woman, in all her romantic and intuitive glory. Ms. di Prima is remarkable because as a poet in her early 20s in 1950s New York, she decided she wanted to be a mother, and a single mother at that.

“I was a poet,” she wrote, continuing, “There was nothing that I could possibly experience, as a human in a female body, that I would not experience …. There should, it seemed to me, be no quarrel between these two aims: to have a baby and to be a poet.” Nevertheless, she continued, “A conflict held me fast.”

Her memoir revolves around this conflict between motherhood and the demands of an artist. At a certain point, overwhelmed by the demands of parenting children alone while running a press, founding an avant-garde theater, protecting her left-wing friends from raids by the F.B.I. and the grinding poverty of an artist’s life in New York City, Ms. di Prima entered into a marriage of convenience with a man she distrusted. He was the ex-boyfriend of her male best friend. Besides its messy origins, this relationship resembles the dream I’ve heard so many straight women describe, in a joking, not joking way — wishing to start a family with a friend, to avoid the complications of romantic love.

But Ms. di Prima is honest about the limitations of the arrangement. She wrote that she avoided the pains of romance, but the man she married is still a domineering, abusive mess, in her recounting. Furthermore, in marriage, she has lost something integral to herself. “One of my most precious and valued possessions was my independence: my struggle for control over my own life,” she wrote, continuing, “I didn’t see that it had no intrinsic value for anyone but myself, that it was a coin that was precious only within the realm, a currency that could not cross borders.”

These words, when I read them, sounded in me like the chime of a tuning fork. I had never before read such a precise description of what marriage asks some people to give up. Those who panic over the rise in the number of single Americans do not see that this statistic includes lives of hard-won independence — lives that still intersect with a community, with a home, with a belief in something wider than oneself. The people clinging to old narratives around singledom and marriage can’t yet see these lives for what they are because, as Ms. di Prima puts it, they are not “an objectively valuable commodity.” Their meaning is “a currency that cannot cross borders.”

These lives threaten the communal narratives currently in place. But what is a threat to some can be to others a glimmer of a new world coming.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/04/opin ... 778d3e6de3

China’s Looming Crisis:

A Shrinking Population

By STEVEN LEE MYERS, JIN WU and CLAIRE FU UPDATED January 17, 2020

Chinese academics recently delivered a stark warning to the country’s leaders: China is facing its most precipitous decline in population in decades, setting the stage for potential demographic, economic and even political crises in the near future.

For years China’s ruling Communist Party implemented a series of policies intended to slow the growth of the world’s most populous nation, including limiting the number of children couples could have to one. The long term effects of those policies mean the country will soon enter an era of “negative growth,” or a contraction in the size of the total population.

A report, issued this month by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, is the latest recognition that while China’s notorious “one child” policy may have achieved its original aim of slowing population growth, it has also created new challenges for the government.

A decline in the birth rate and an increase in life expectancy means there will soon be too few workers able to support an enormous and aging population, the academy warned. The academy estimated the contraction would begin in 2027, though others believe it would come sooner or has already begun.

The government has recognized the worrisome demographic trend and in 2013 began easing enforcement of the “one child” policy in certain circumstances. It then raised the limit to two children for all families in 2016, in hopes of encouraging a baby boom. It did not work.

After a brief uptick that year, the birth rate fell again in 2017, with 17.2 million babies born compared to 17.9 in 2016. Although the number of families having a second child rose, the overall number of births continued to drop.

In 2018, the total number of births fell to 15.2 million, a drop of nearly 12 percent nationally from 2017. Some cities and provinces have reported declines in local birth rates of as much as 35 percent.

On Friday, the National Bureau of Statistics announced that in 2019, the total number of births fell for the third year, to 14.6 million.

The fertility rate required to maintain population levels is 2.1 children per woman, a figure known as “replacement level fertility.”

The fertility rates in many advanced economies have fallen as their societies have become wealthier and older.

China’s fertility rate has officially fallen to 1.6 children per woman, but even that number is disputed.

Yi Fuxian, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, has written that China’s government has obscured the actual fertility rate to disguise the disastrous ramifications of the “one child” policy. According to his calculations, the fertility rate averaged 1.18 between 2010 and 2018.

As in other countries, there are myriad reasons for the declining birth rate, including rising prosperity and new opportunities for women. China’s economic expansion has created a society where many young couples now struggle with economic pressures -- including rising education and housing costs -- making it difficult to have even one child, let alone two.

But the most profound cause of the drop, Professor Yi and others said, was the “one child” policy. Fewer children were born, and because of cultural preferences for male offspring, fewer of them were girls.

Chinese women born during the years following the “one child” policy are now reaching or have already passed their peak fertility age. There are simply not enough of them to sustain the country’s population level, despite new efforts by the government to encourage families to have two children.

The looming demographic crisis could be the Achilles heel of China’s stunning economic transformation over the last 40 years.

The declining population could create an even greater burden on China’s economy and its labor force. With fewer workers in the future, the government could struggle to pay for a population that is growing older and living longer.