General Art & Architecture of Interest

History, the arts, and pandemics

Paintings, literature, and films, amongst other forms of art, are repositories of a society’s collective memory. They have much to tell us about prior pandemics, their impact, and what we can learn from these impressions today.

“Ars longa, vitas brevis” (Art is long, life is short) is an aphorism attributed to the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates.

It has been said that art imitates life; yet, we can look back through the annals of history and see that in fact today, life imitates art, offering us a sense of déjà vu. There have been various pandemics in the past, and we should see the current coronavirus crisis in perspective, while we seclude ourselves from the world around us.

The past and the present

The Plague of Justinian in the 5th century affected Constantinople and led to over 30 million deaths, half the world’s population; pestilence was recorded at the time of the Prophet (peace be upon him and his family), with perhaps 25,000 dying during the plague of Emmaus (Syria), including some of his Companions; the Black Death of the 14th century caused 200 million deaths; smallpox eradicated 90 percent of the indigenous people of the Americas, allowing Cortez to conquer the Aztecs; and AIDS led to 35 million lives being lost.

Many historic catastrophes have been depicted by artists, perhaps the most famous and vivid canvas being “The Triumph of Death,” painted by Pieter Bruegel the Elder in 1562, a time between the plagues and wars that engulfed Europe. Many others have painted scenes of epidemics illustrating the despair and helplessness experienced at such times. We are fortunate that our current situation, while challenging, is no comparison to those of times past, as we have modern medicine, facilities, and hope — commodities unavailable then.

“April is the cruelest month,” wrote poet T.S. Eliot in his masterpiece, “The Waste Land.” He wrote after the First World War, when millions had suffered and perished from the ravages of battle and the 1917 influenza pandemic, misnamed the “Spanish Flu.” Europeans at the time thought they indeed faced the apocalypse.

During the next war, Albert Camus’ 1947 novel, The Plague, described an Algerian town afflicted and quarantined a century earlier due to cholera. It has been interpreted as an allegory, comparing the devastation caused by uncontrollable forces of nature to those caused by humanity out of control.

That same year, Iraqi poet Nazik al-Malaika wrote about the agony of cholera engulfing Cairo, a grief-stricken city with 10,000 deaths. It is instructive to read her poem and contrast the description to our own times, despite our healthcare system being strained to capacity.

“It is dawn.

Listen to the footsteps of the passerby,

in the silence of the dawn.

Listen, look at the mourning processions,

ten, twenty, no… countless.

…

Everywhere lies a corpse, mourned

without a eulogy or a moment of silence.

…

Humanity protests against the crimes of death.

…

Even the gravedigger has succumbed,

the muezzin is dead,

and who will eulogize the dead?

…

O Egypt, my heart is torn by the ravages of death.”

Tripoli, Libya, was also afflicted by the plague in 1785. Miss Tully, an English resident at the time, wrote about fumigation and social distancing, as well as the spread of the disease to Sfax, Tunisia, where 15,000 perished — half the town’s population.

Even earlier, in 1349, Syrian historian Ibn al-Wardi, in “An Essay on the Report of the Pestilence,” described the Black Death with an eerie similarity to what we face today.

The plague began in the land of darkness. China was not preserved from it. The plague infected the Indians in India, the Sind, the Persians, and the Crimea. The plague destroyed mankind in Cairo. It stilled all movement in Alexandria. Then, the plague turned to Upper Egypt. The plague attacked Gaza, trapped Sidon, and Beirut. Next, it directed its shooting arrows to Damascus. There the plague sat like a lion on a throne and swayed with power, killing daily one thousand or more and destroying the population.

Al-Wardi ends with a prayer: “Oh God, it is acting by Your command. Lift this from us. It happens where You wish; keep the plague from us.” He was to succumb to the disease himself two days after completing his work.

The prescience of film

Film buffs may be familiar with some recent productions that have dealt with imaginary epidemics. They include the 1995 film, Outbreak, starring Dustin Hoffman, and Contagion, which describes societal collapse following a virus pandemic, one of the latest in this genre. It does, however, end on a positive note, with the line, “Society is better off in a plague when everyone works together and cares for one another, and tries to muddle through a nightmare.” Certainly, an apt description of what we are witnessing today, as we grasp at numerous potential solutions for salvation.

The acclaimed South Korean film, My Secret Terrius, mentions coronavirus and depicts social distancing as a prophylactic. And the popular animated children’s film, Tangled, tells us that Rapunzel lived in the kingdom of Corona, was kidnapped by a witch, and imprisoned in a tower. Children today will relate to the main character in this tale: claustrophobic and unable to play outside. This story may have its origins in the story of Rudabeh, found in the Persian epic, the Shahnameh of the 11th century.

History repeated

“There is no present or future — only the past, happening over and over again now,” wrote playwright Eugene O'Neill. It certainly seems so, as we recall bubonic plague, tuberculosis, typhoid, cholera, the “Spanish Flu,” polio, AIDS, SARS, and Ebola — just a few of the epidemics that have decimated populations in recent memory and recorded in great detail in historical accounts, as well as in art and literature.

In our globalised world, the threat of disease is even more palpable now, as populations cross frontiers in a matter of hours, perhaps carrying with them invisible microbes.

We can recall the leadership of Mawlana Sultan Mahomed Shah during the bubonic plague that engulfed Bombay in 1897. He provided facilities and supported the research of a vaccine there that eventually countered the disease. As the public was wary of the vaccine, he led by example, writing in his Memoirs: “It was in my power to set an example. I had myself publicly inoculated, and I took care to see that the news of what I had done was spread as far as possible and as quickly as possible.” Emboldened by his example, countless others in the city followed.

The threat of pandemics was noted by Mawlana Hazar Imam in his 2010 LaFontaine-Baldwin lecture, when he said, “Almost everything now seems to ‘flow’ globally — people and images, money and credit, goods and services, microbes and viruses, pollution and armaments, crime and terror.” The veracity of that observation is clear.

Lessons from the pandemic

What do these impressions of life and death by artists, poets, and novelists inform us about conditions today? Perhaps the most important lesson is that of humility, that nature is a force far greater than the ability of humanity to control and mould to its will. Whether it be weather-related events, natural disasters, or epidemics, we have limited responses.

We have been given a collective shock with the realisation that we are in fact not masters of the universe, and our ability to determine the future is not all in our control. However, there are actions that can be taken to mitigate disasters for the human race and its future. This may be a warning to show greater concern for the environment, as Pope Francis suggested recently. We do understand the causes of environmental degradation, and that the environment must be protected and nurtured, as it is the source of life, from the water we consume, to the trees that offer us shade and the clean air we breathe.

In our march for progress, humans have polluted the atmosphere, the rivers, and the seas. Yet, an unseen microbe can be the cause of destruction, affecting anyone and everyone, from the leaders of countries, to the rich and poor alike, and even to the remotest tribe, the Yanomami, hidden deep in the Amazon forest. Indeed, scientists have suggested a link between deforestation and the rise in infectious diseases, of which the Amazon region is a prime example.

Today’s heroes

Traditional wars are fought and won with soldiers, superior weapons, military strategy, and tenacity. None of these are useful for today’s global threat. It is the doctors, nurses, emergency personnel, farm workers picking vegetables and fruit, delivery drivers bringing us supplies, and the grocery store staff on the frontlines, risking their lives in a war to save the rest of us, sometimes losing their own. They are the soldiers of today, heroes and heroines who deserve medals in their effort to fight this scourge, and who offer us hope.

Our own Ismaili healthcare workers all over the world are a part of this contingent of soldiers, working in the emergency rooms and ICU wards. Others from our global Jamat have offered personal protective equipment from their stores, made and donated masks, as well as food and needed items to hospitals, neighbours, and others. We are all in this together.

This crisis will end but it will not be forgotten, as there are lessons here for future generations. And because artists and novelists are keen sensors who reflect the social conditions of their time, this episode in history, with its impact, failings, successes, and new soldiers, will be revisited, recalled, and immortalised, both in word and paint — for life may be short but art transcends time.

https://the.ismaili/global/news/feature ... -pandemics

Paintings, literature, and films, amongst other forms of art, are repositories of a society’s collective memory. They have much to tell us about prior pandemics, their impact, and what we can learn from these impressions today.

“Ars longa, vitas brevis” (Art is long, life is short) is an aphorism attributed to the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates.

It has been said that art imitates life; yet, we can look back through the annals of history and see that in fact today, life imitates art, offering us a sense of déjà vu. There have been various pandemics in the past, and we should see the current coronavirus crisis in perspective, while we seclude ourselves from the world around us.

The past and the present

The Plague of Justinian in the 5th century affected Constantinople and led to over 30 million deaths, half the world’s population; pestilence was recorded at the time of the Prophet (peace be upon him and his family), with perhaps 25,000 dying during the plague of Emmaus (Syria), including some of his Companions; the Black Death of the 14th century caused 200 million deaths; smallpox eradicated 90 percent of the indigenous people of the Americas, allowing Cortez to conquer the Aztecs; and AIDS led to 35 million lives being lost.

Many historic catastrophes have been depicted by artists, perhaps the most famous and vivid canvas being “The Triumph of Death,” painted by Pieter Bruegel the Elder in 1562, a time between the plagues and wars that engulfed Europe. Many others have painted scenes of epidemics illustrating the despair and helplessness experienced at such times. We are fortunate that our current situation, while challenging, is no comparison to those of times past, as we have modern medicine, facilities, and hope — commodities unavailable then.

“April is the cruelest month,” wrote poet T.S. Eliot in his masterpiece, “The Waste Land.” He wrote after the First World War, when millions had suffered and perished from the ravages of battle and the 1917 influenza pandemic, misnamed the “Spanish Flu.” Europeans at the time thought they indeed faced the apocalypse.

During the next war, Albert Camus’ 1947 novel, The Plague, described an Algerian town afflicted and quarantined a century earlier due to cholera. It has been interpreted as an allegory, comparing the devastation caused by uncontrollable forces of nature to those caused by humanity out of control.

That same year, Iraqi poet Nazik al-Malaika wrote about the agony of cholera engulfing Cairo, a grief-stricken city with 10,000 deaths. It is instructive to read her poem and contrast the description to our own times, despite our healthcare system being strained to capacity.

“It is dawn.

Listen to the footsteps of the passerby,

in the silence of the dawn.

Listen, look at the mourning processions,

ten, twenty, no… countless.

…

Everywhere lies a corpse, mourned

without a eulogy or a moment of silence.

…

Humanity protests against the crimes of death.

…

Even the gravedigger has succumbed,

the muezzin is dead,

and who will eulogize the dead?

…

O Egypt, my heart is torn by the ravages of death.”

Tripoli, Libya, was also afflicted by the plague in 1785. Miss Tully, an English resident at the time, wrote about fumigation and social distancing, as well as the spread of the disease to Sfax, Tunisia, where 15,000 perished — half the town’s population.

Even earlier, in 1349, Syrian historian Ibn al-Wardi, in “An Essay on the Report of the Pestilence,” described the Black Death with an eerie similarity to what we face today.

The plague began in the land of darkness. China was not preserved from it. The plague infected the Indians in India, the Sind, the Persians, and the Crimea. The plague destroyed mankind in Cairo. It stilled all movement in Alexandria. Then, the plague turned to Upper Egypt. The plague attacked Gaza, trapped Sidon, and Beirut. Next, it directed its shooting arrows to Damascus. There the plague sat like a lion on a throne and swayed with power, killing daily one thousand or more and destroying the population.

Al-Wardi ends with a prayer: “Oh God, it is acting by Your command. Lift this from us. It happens where You wish; keep the plague from us.” He was to succumb to the disease himself two days after completing his work.

The prescience of film

Film buffs may be familiar with some recent productions that have dealt with imaginary epidemics. They include the 1995 film, Outbreak, starring Dustin Hoffman, and Contagion, which describes societal collapse following a virus pandemic, one of the latest in this genre. It does, however, end on a positive note, with the line, “Society is better off in a plague when everyone works together and cares for one another, and tries to muddle through a nightmare.” Certainly, an apt description of what we are witnessing today, as we grasp at numerous potential solutions for salvation.

The acclaimed South Korean film, My Secret Terrius, mentions coronavirus and depicts social distancing as a prophylactic. And the popular animated children’s film, Tangled, tells us that Rapunzel lived in the kingdom of Corona, was kidnapped by a witch, and imprisoned in a tower. Children today will relate to the main character in this tale: claustrophobic and unable to play outside. This story may have its origins in the story of Rudabeh, found in the Persian epic, the Shahnameh of the 11th century.

History repeated

“There is no present or future — only the past, happening over and over again now,” wrote playwright Eugene O'Neill. It certainly seems so, as we recall bubonic plague, tuberculosis, typhoid, cholera, the “Spanish Flu,” polio, AIDS, SARS, and Ebola — just a few of the epidemics that have decimated populations in recent memory and recorded in great detail in historical accounts, as well as in art and literature.

In our globalised world, the threat of disease is even more palpable now, as populations cross frontiers in a matter of hours, perhaps carrying with them invisible microbes.

We can recall the leadership of Mawlana Sultan Mahomed Shah during the bubonic plague that engulfed Bombay in 1897. He provided facilities and supported the research of a vaccine there that eventually countered the disease. As the public was wary of the vaccine, he led by example, writing in his Memoirs: “It was in my power to set an example. I had myself publicly inoculated, and I took care to see that the news of what I had done was spread as far as possible and as quickly as possible.” Emboldened by his example, countless others in the city followed.

The threat of pandemics was noted by Mawlana Hazar Imam in his 2010 LaFontaine-Baldwin lecture, when he said, “Almost everything now seems to ‘flow’ globally — people and images, money and credit, goods and services, microbes and viruses, pollution and armaments, crime and terror.” The veracity of that observation is clear.

Lessons from the pandemic

What do these impressions of life and death by artists, poets, and novelists inform us about conditions today? Perhaps the most important lesson is that of humility, that nature is a force far greater than the ability of humanity to control and mould to its will. Whether it be weather-related events, natural disasters, or epidemics, we have limited responses.

We have been given a collective shock with the realisation that we are in fact not masters of the universe, and our ability to determine the future is not all in our control. However, there are actions that can be taken to mitigate disasters for the human race and its future. This may be a warning to show greater concern for the environment, as Pope Francis suggested recently. We do understand the causes of environmental degradation, and that the environment must be protected and nurtured, as it is the source of life, from the water we consume, to the trees that offer us shade and the clean air we breathe.

In our march for progress, humans have polluted the atmosphere, the rivers, and the seas. Yet, an unseen microbe can be the cause of destruction, affecting anyone and everyone, from the leaders of countries, to the rich and poor alike, and even to the remotest tribe, the Yanomami, hidden deep in the Amazon forest. Indeed, scientists have suggested a link between deforestation and the rise in infectious diseases, of which the Amazon region is a prime example.

Today’s heroes

Traditional wars are fought and won with soldiers, superior weapons, military strategy, and tenacity. None of these are useful for today’s global threat. It is the doctors, nurses, emergency personnel, farm workers picking vegetables and fruit, delivery drivers bringing us supplies, and the grocery store staff on the frontlines, risking their lives in a war to save the rest of us, sometimes losing their own. They are the soldiers of today, heroes and heroines who deserve medals in their effort to fight this scourge, and who offer us hope.

Our own Ismaili healthcare workers all over the world are a part of this contingent of soldiers, working in the emergency rooms and ICU wards. Others from our global Jamat have offered personal protective equipment from their stores, made and donated masks, as well as food and needed items to hospitals, neighbours, and others. We are all in this together.

This crisis will end but it will not be forgotten, as there are lessons here for future generations. And because artists and novelists are keen sensors who reflect the social conditions of their time, this episode in history, with its impact, failings, successes, and new soldiers, will be revisited, recalled, and immortalised, both in word and paint — for life may be short but art transcends time.

https://the.ismaili/global/news/feature ... -pandemics

A Cog in the Machine of Creation

The many roles involved in producing a film rule out the notion of a single, indispensable artist.

As an artist, I am a creator, though referring to myself that way makes me somewhat uncomfortable. For most of my life, the word “creator” has meant the Creator of all things, especially in the native tradition, and I would not by any means compare my meager efforts at creation to Creation.

But art is truly an act of creation. And creation is an act of art.

When we create art, it’s a product of three components: the mind, the heart and our past experiences. As an actor, sculptor and author, I have found that this interconnectedness is a large part of why art matters.

The mind, of course, is where initial ideas are conceived, whether through whimsy, inspiration or suggestion. What matters at the inception of creation is deciding whether an idea is worth pursuing. The heart then reveals to us how we feel about the idea, and we again ponder the worthiness of the pursuit. Past experiences help us weigh the personal significance of the creation we are considering. As artists, we ask ourselves: Will it serve a purpose beyond our own need to create? Does it need to?

As an actor, I have at times wondered whether acting is a true art form. Is an actor merely an interpreter of an idea created in a screenplay, script or play? Is performance in this context merely a craft, or is it an act of creation itself?

In this context, the answer might seem simple: The writer is the artist, the creator. The actor is the journeyman who interprets the plan, the story to be told.

But the actor must also rely on many other people to do his work: makeup artists, hair stylists, costume designers, directors. Photography and set design are also prime considerations. The many roles involved in producing a film rule out the notion of a sole creator or artist. The actor becomes a cog in a larger machine of creation. And each cog is an absolute necessity.

As for the question of whether an actor is a creator or an interpreter, I lean toward considering myself an indispensable craftsman tasked with a particular act of creation: a performance worthy of the story being told.

While the original idea may have been created by another, it falls to the performer to fit the situation.

Filmmaking is an especially collaborative function, and acting encompasses a bit of craftsmanship. “Dances With Wolves,” for instance, the 1990 film in which I played a Pawnee warrior, required the coordination of thousands of bison for a hunting scene, and battle scenes featured dozens of riders on horseback, along with actors doing their part to bring to life a unique story. I had to learn some of the Pawnee language to better portray my character. In fact, in my career I have spoken some 20 languages for various roles, including one that did not exist: I was asked to work with linguists crafting the language of the Na’vi, the Indigenous culture in “Avatar,” because I spoke Cherokee and had studied phonetic languages, a valuable part of my past that I brought to that film.

As a Native American actor, I’ve remained keenly aware that the wars and invasions that ravaged native populations throughout the Americas have never really ended. That knowledge, along with my own past experience, enabled me to empathetically portray characters like the Apache warrior Geronimo onscreen, and to better convey the deep sense of injustice that the real Geronimo faced.

While as an actor I’m either an arty craftsman or a crafty artist, adding and building on another’s idea, as a sculptor carving stone I find things a bit different. I remove rather than build, shaping and carving, transforming a stone from its original organic form into something familiar and pleasing to the eye. These carvings satisfy both my need to create and control the process as much as the stone allows; an added factor is the journey of creating something unique. That these pieces of art are appreciated is, of course, additionally gratifying.

I can say the same for book writing: “The Adventures of Billy Bean,” a children’s book I wrote in Cherokee and English many years ago, was also an act of creating characters in my mind and heart, and rooted in past experiences. I hope that the stories in the book provided entertainment and an uplifting message about life for young people becoming acquainted with the world around them.

If sculpting makes me a sculptor, then so be it. If writing makes me an author, then so be it. With minds, hearts and pasts, we all commit acts of creation.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/31/opin ... 778d3e6de3

The many roles involved in producing a film rule out the notion of a single, indispensable artist.

As an artist, I am a creator, though referring to myself that way makes me somewhat uncomfortable. For most of my life, the word “creator” has meant the Creator of all things, especially in the native tradition, and I would not by any means compare my meager efforts at creation to Creation.

But art is truly an act of creation. And creation is an act of art.

When we create art, it’s a product of three components: the mind, the heart and our past experiences. As an actor, sculptor and author, I have found that this interconnectedness is a large part of why art matters.

The mind, of course, is where initial ideas are conceived, whether through whimsy, inspiration or suggestion. What matters at the inception of creation is deciding whether an idea is worth pursuing. The heart then reveals to us how we feel about the idea, and we again ponder the worthiness of the pursuit. Past experiences help us weigh the personal significance of the creation we are considering. As artists, we ask ourselves: Will it serve a purpose beyond our own need to create? Does it need to?

As an actor, I have at times wondered whether acting is a true art form. Is an actor merely an interpreter of an idea created in a screenplay, script or play? Is performance in this context merely a craft, or is it an act of creation itself?

In this context, the answer might seem simple: The writer is the artist, the creator. The actor is the journeyman who interprets the plan, the story to be told.

But the actor must also rely on many other people to do his work: makeup artists, hair stylists, costume designers, directors. Photography and set design are also prime considerations. The many roles involved in producing a film rule out the notion of a sole creator or artist. The actor becomes a cog in a larger machine of creation. And each cog is an absolute necessity.

As for the question of whether an actor is a creator or an interpreter, I lean toward considering myself an indispensable craftsman tasked with a particular act of creation: a performance worthy of the story being told.

While the original idea may have been created by another, it falls to the performer to fit the situation.

Filmmaking is an especially collaborative function, and acting encompasses a bit of craftsmanship. “Dances With Wolves,” for instance, the 1990 film in which I played a Pawnee warrior, required the coordination of thousands of bison for a hunting scene, and battle scenes featured dozens of riders on horseback, along with actors doing their part to bring to life a unique story. I had to learn some of the Pawnee language to better portray my character. In fact, in my career I have spoken some 20 languages for various roles, including one that did not exist: I was asked to work with linguists crafting the language of the Na’vi, the Indigenous culture in “Avatar,” because I spoke Cherokee and had studied phonetic languages, a valuable part of my past that I brought to that film.

As a Native American actor, I’ve remained keenly aware that the wars and invasions that ravaged native populations throughout the Americas have never really ended. That knowledge, along with my own past experience, enabled me to empathetically portray characters like the Apache warrior Geronimo onscreen, and to better convey the deep sense of injustice that the real Geronimo faced.

While as an actor I’m either an arty craftsman or a crafty artist, adding and building on another’s idea, as a sculptor carving stone I find things a bit different. I remove rather than build, shaping and carving, transforming a stone from its original organic form into something familiar and pleasing to the eye. These carvings satisfy both my need to create and control the process as much as the stone allows; an added factor is the journey of creating something unique. That these pieces of art are appreciated is, of course, additionally gratifying.

I can say the same for book writing: “The Adventures of Billy Bean,” a children’s book I wrote in Cherokee and English many years ago, was also an act of creating characters in my mind and heart, and rooted in past experiences. I hope that the stories in the book provided entertainment and an uplifting message about life for young people becoming acquainted with the world around them.

If sculpting makes me a sculptor, then so be it. If writing makes me an author, then so be it. With minds, hearts and pasts, we all commit acts of creation.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/31/opin ... 778d3e6de3

Erdogan Talks of Making Hagia Sophia a Mosque Again, to International Dismay

The World Heritage site was once a potent symbol of Christian-Muslim rivalry, and it could become one once more.

ISTANBUL — Since it was built in the sixth century, changing hands from empire to empire, Hagia Sophia has been a Byzantine cathedral, a mosque under the Ottomans and finally a museum, making it one of the world’s most potent symbols of Christian-Muslim rivalry and of Turkey’s more recent devotion to secularism.

Now President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is making moves to declare it a working mosque once more, fulfilling a dream for himself, his supporters and conservative Muslims far beyond Turkey’s shores — but threatening to set off an international furor.

The very idea of changing the monument’s status has escalated tensions with Turkey’s longtime rival, Greece; upset Christians around the world; and set off a chorus of dismay from political and religious leaders as diverse as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Patriarch Kirill of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Mr. Erdogan’s opponents say he has raised the issue of restoring Hagia Sophia as a mosque every time he has faced a political crisis, using it to stir supporters in his nationalist and conservative religious base.

But given the severity of the challenges Mr. Erdogan faces after 18 years at the helm of Turkish politics, there may be more reason than ever to take the talk seriously. Having lost Istanbul in local elections last year, the president has watched the standing of his party continue to slide in the polls as the Covid-19 pandemic has further undone a vulnerable economy.

On July 2, a Turkish administrative court ruled on whether to restore Hagia Sophia, or Ayasofya, its Turkish name, as a mosque, and revoke an 80-year-old decree that declared it a museum under Turkey’s secular state. The ruling will be announced within two weeks, and then Mr. Erdogan is expected to make the final decision.

For more than 25 years since he became mayor of Istanbul, Mr. Erdogan has been working to leave his stamp on his beloved home city. He cleaned up the Golden Horn, built bridges and tunnels across the famous waters and placed new mosques at the most prominent sites.

But it is Hagia Sophia, one of the oldest and architecturally one of the most impressive cathedrals in the world, that commands pride of place on the historical peninsula.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/08/worl ... 778d3e6de3

The World Heritage site was once a potent symbol of Christian-Muslim rivalry, and it could become one once more.

ISTANBUL — Since it was built in the sixth century, changing hands from empire to empire, Hagia Sophia has been a Byzantine cathedral, a mosque under the Ottomans and finally a museum, making it one of the world’s most potent symbols of Christian-Muslim rivalry and of Turkey’s more recent devotion to secularism.

Now President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is making moves to declare it a working mosque once more, fulfilling a dream for himself, his supporters and conservative Muslims far beyond Turkey’s shores — but threatening to set off an international furor.

The very idea of changing the monument’s status has escalated tensions with Turkey’s longtime rival, Greece; upset Christians around the world; and set off a chorus of dismay from political and religious leaders as diverse as Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Patriarch Kirill of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Mr. Erdogan’s opponents say he has raised the issue of restoring Hagia Sophia as a mosque every time he has faced a political crisis, using it to stir supporters in his nationalist and conservative religious base.

But given the severity of the challenges Mr. Erdogan faces after 18 years at the helm of Turkish politics, there may be more reason than ever to take the talk seriously. Having lost Istanbul in local elections last year, the president has watched the standing of his party continue to slide in the polls as the Covid-19 pandemic has further undone a vulnerable economy.

On July 2, a Turkish administrative court ruled on whether to restore Hagia Sophia, or Ayasofya, its Turkish name, as a mosque, and revoke an 80-year-old decree that declared it a museum under Turkey’s secular state. The ruling will be announced within two weeks, and then Mr. Erdogan is expected to make the final decision.

For more than 25 years since he became mayor of Istanbul, Mr. Erdogan has been working to leave his stamp on his beloved home city. He cleaned up the Golden Horn, built bridges and tunnels across the famous waters and placed new mosques at the most prominent sites.

But it is Hagia Sophia, one of the oldest and architecturally one of the most impressive cathedrals in the world, that commands pride of place on the historical peninsula.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/08/worl ... 778d3e6de3

To deface a monument is to engage critically with history

The head of a statue of Sir John A. MacDonald is shown torn down following a demonstration in Montreal, on Aug. 29, 2020.

Take it from a historian: If heads are going to roll, it’s preferable they be cast in bronze.

We tend to have inconsistent opinions regarding the toppling of monuments. When they’re brought down by mobs of jubilant Iraqis or Eastern Europeans, we celebrate the triumph of liberty and freedom of expression – our core democratic values. But when it happens here at home, it’s all anarchy and cancel culture.

If it rubs you the wrong way to know that people might compare aspects of such tyrants to Sir John A. Macdonald, whose statue was pulled down in Montreal by protesters this weekend, you’re likely not Indigenous. We tend to have a remarkable ability in this country to identify brutality abroad, but also to ignore it here at home in our own history.

Chalk it up to a maddeningly persistent national inferiority complex, but we often make false idols of our forebears. Statue fetishists insist that removing them erases history, and with this thinking, we’re left with a pedophile watching over tourists in Vancouver, a slave owner welcoming university students in Montreal and vast swaths of Kingston dedicated to the man chiefly responsible for our national shame.

If I had to hazard a guess, up until Saturday most Canadians likely had no idea that the largest and most elaborate monument to Macdonald is in, of all places, downtown Montreal. Fewer still know that the statue had been decapitated once before, in the wake of the stillborn Charlottetown Accord, and left headless for a couple years in the mid-1990s. It was more than a smidge ironic to now see Quebec nationalists of the hard and soft varieties jumping on the outrage bandwagon, demanding that order must be maintained.

Indeed, most of us likely don’t think twice about monuments until someone defaces them. Most Canadians were surely surprised to learn of a monument in Oakville, Ont., devoted to Nazi collaborators after it was vandalized in June – and shocked when Halton Police opened a since-suspended hate-crime investigation into the incident. Meanwhile, our leaders will appeal for calm and dialogue on matters of contested commemoration, but they will rarely admit that, left alone, monuments often say very little. Indeed, for the most part, monuments and memorials are little more than park decorations. Defenders of the status quo may swear that monuments are history incarnate, but without such instances of direct action and public participation, no conversation actually occurs.

It only took toppling a single statue and suddenly we’re all talking about Macdonald’s legacy. A blockbuster biopic wouldn’t generate half as much discussion. And it’s a discussion we desperately need to have. Macdonald played a central role in the dispossession, disenfranchisement and damn-near disappearance of the Indigenous of this land. Over a century-and-a-half later, we’re still coming to terms with the mess he created. Late biographer Richard Gwyn perhaps accidentally demonstrated the extent of Canadians’ aversion to historical complexity when he speciously stated “no Macdonald, no Canada,” as if such reductionism was wildly illuminating.

The nation has changed considerably since Confederation. Our monuments? Less so. A considerable bulk of our nation’s historic markers and monuments predate the Second World War and represent a particularly imperial interpretation of our history. Indeed, when the monument in question was unveiled in Montreal in 1895, Macdonald was lauded not so much for founding Canada but for his loyal service to the British Empire.

Meanwhile, the recently renovated city park in which the Macdonald monument sits contains no contemporary public art and says almost nothing about Canadian history. In doing so, however, Place du Canada unintentionally speaks volumes about the nation. It is a large open space, paved charcoal-grey and adorned with reminders of death, war and empire. Along the plaza’s edge are cannons from the Crimean War, the Macdonald monument, the city’s cenotaph, and an arbitrary howitzer, pointing at nothing in particular. Surrounded by old baggage, this great grey emptiness awaits a statement about who we truly are and what we hope to be.

We are long overdue for new commemoration. Statuary does little to inform; rather than illuminate, it tends to occlude historical reality by literally putting people on pedestals.

We have the means and the imagination to do much better. All that’s missing is the courage to step boldly forward, accepting that we come not from greatness, but aspire to it.

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion ... VgMaFxFnIY

The head of a statue of Sir John A. MacDonald is shown torn down following a demonstration in Montreal, on Aug. 29, 2020.

Take it from a historian: If heads are going to roll, it’s preferable they be cast in bronze.

We tend to have inconsistent opinions regarding the toppling of monuments. When they’re brought down by mobs of jubilant Iraqis or Eastern Europeans, we celebrate the triumph of liberty and freedom of expression – our core democratic values. But when it happens here at home, it’s all anarchy and cancel culture.

If it rubs you the wrong way to know that people might compare aspects of such tyrants to Sir John A. Macdonald, whose statue was pulled down in Montreal by protesters this weekend, you’re likely not Indigenous. We tend to have a remarkable ability in this country to identify brutality abroad, but also to ignore it here at home in our own history.

Chalk it up to a maddeningly persistent national inferiority complex, but we often make false idols of our forebears. Statue fetishists insist that removing them erases history, and with this thinking, we’re left with a pedophile watching over tourists in Vancouver, a slave owner welcoming university students in Montreal and vast swaths of Kingston dedicated to the man chiefly responsible for our national shame.

If I had to hazard a guess, up until Saturday most Canadians likely had no idea that the largest and most elaborate monument to Macdonald is in, of all places, downtown Montreal. Fewer still know that the statue had been decapitated once before, in the wake of the stillborn Charlottetown Accord, and left headless for a couple years in the mid-1990s. It was more than a smidge ironic to now see Quebec nationalists of the hard and soft varieties jumping on the outrage bandwagon, demanding that order must be maintained.

Indeed, most of us likely don’t think twice about monuments until someone defaces them. Most Canadians were surely surprised to learn of a monument in Oakville, Ont., devoted to Nazi collaborators after it was vandalized in June – and shocked when Halton Police opened a since-suspended hate-crime investigation into the incident. Meanwhile, our leaders will appeal for calm and dialogue on matters of contested commemoration, but they will rarely admit that, left alone, monuments often say very little. Indeed, for the most part, monuments and memorials are little more than park decorations. Defenders of the status quo may swear that monuments are history incarnate, but without such instances of direct action and public participation, no conversation actually occurs.

It only took toppling a single statue and suddenly we’re all talking about Macdonald’s legacy. A blockbuster biopic wouldn’t generate half as much discussion. And it’s a discussion we desperately need to have. Macdonald played a central role in the dispossession, disenfranchisement and damn-near disappearance of the Indigenous of this land. Over a century-and-a-half later, we’re still coming to terms with the mess he created. Late biographer Richard Gwyn perhaps accidentally demonstrated the extent of Canadians’ aversion to historical complexity when he speciously stated “no Macdonald, no Canada,” as if such reductionism was wildly illuminating.

The nation has changed considerably since Confederation. Our monuments? Less so. A considerable bulk of our nation’s historic markers and monuments predate the Second World War and represent a particularly imperial interpretation of our history. Indeed, when the monument in question was unveiled in Montreal in 1895, Macdonald was lauded not so much for founding Canada but for his loyal service to the British Empire.

Meanwhile, the recently renovated city park in which the Macdonald monument sits contains no contemporary public art and says almost nothing about Canadian history. In doing so, however, Place du Canada unintentionally speaks volumes about the nation. It is a large open space, paved charcoal-grey and adorned with reminders of death, war and empire. Along the plaza’s edge are cannons from the Crimean War, the Macdonald monument, the city’s cenotaph, and an arbitrary howitzer, pointing at nothing in particular. Surrounded by old baggage, this great grey emptiness awaits a statement about who we truly are and what we hope to be.

We are long overdue for new commemoration. Statuary does little to inform; rather than illuminate, it tends to occlude historical reality by literally putting people on pedestals.

We have the means and the imagination to do much better. All that’s missing is the courage to step boldly forward, accepting that we come not from greatness, but aspire to it.

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion ... VgMaFxFnIY

To Protest Colonialism, He Takes Artifacts From Museums

Mwazulu Diyabanza will appear in a Paris court this month after he tried to make off with an African treasure he says was looted. France and its attitude to the colonial past will be on trial, too.

PARIS — Early one afternoon in June, the Congolese activist Mwazulu Diyabanza walked into the Quai Branly Museum, the riverfront institution that houses treasures from France’s former colonies, and bought a ticket. Together with four associates, he wandered around the Paris museum’s African collections, reading the labels and admiring the treasures on show.

Yet what started as a standard museum outing soon escalated into a raucous demonstration as Mr. Diyabanza began denouncing colonial-era cultural theft while a member of his group filmed the speech and live-streamed it via Facebook. With another group member’s help, he then forcefully removed a slender 19th-century wooden funerary post, from a region that is now in Chad or Sudan, and headed for the exit. Museum guards stopped him before he could leave.

The next month, in the southern French city of Marseille, Mr. Diyabanza seized an artifact from the Museum of African, Oceanic and Native American Arts in another live-streamed protest, before being halted by security. And earlier this month, in a third action that was also broadcast on Facebook, he and other activists took a Congolese funeral statue from the Afrika Museum in Berg en Dal, the Netherlands, before guards stopped him again.

Now, Mr. Diyabanza, the spokesman for a Pan-African movement that seeks reparations for colonialism, slavery and cultural expropriation, is set to stand trial in Paris on Sept. 30. Along with the four associates from the Quai Branly action, he will face a charge of attempted theft, in a case that is also likely to put France on the stand for its colonial track record and for holding so much of sub-Saharan Africa’s cultural heritage — 90,000 or so objects — in its museums.

“The fact that I had to pay my own money to see what had been taken by force, this heritage that belonged back home where I come from — that’s when the decision was made to take action,” said Mr. Diyabanza in an interview in Paris this month.

Describing the Quai Branly as “a museum that contains stolen objects,” he added, “There is no ban on an owner taking back his property the moment he comes across it.”

President Emmanuel Macron pledged in 2017 to give back much of Africa’s heritage held by France’s museums, and commissioned two academics to draw up a report on how to do it.

The 2018 report, by Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr, said any artifacts removed from sub-Saharan Africa in colonial times should be permanently returned if they were “taken by force, or presumed to be acquired through inequitable conditions,” and if their countries of origin asked for them.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/21/arts ... ogin-email

Mwazulu Diyabanza will appear in a Paris court this month after he tried to make off with an African treasure he says was looted. France and its attitude to the colonial past will be on trial, too.

PARIS — Early one afternoon in June, the Congolese activist Mwazulu Diyabanza walked into the Quai Branly Museum, the riverfront institution that houses treasures from France’s former colonies, and bought a ticket. Together with four associates, he wandered around the Paris museum’s African collections, reading the labels and admiring the treasures on show.

Yet what started as a standard museum outing soon escalated into a raucous demonstration as Mr. Diyabanza began denouncing colonial-era cultural theft while a member of his group filmed the speech and live-streamed it via Facebook. With another group member’s help, he then forcefully removed a slender 19th-century wooden funerary post, from a region that is now in Chad or Sudan, and headed for the exit. Museum guards stopped him before he could leave.

The next month, in the southern French city of Marseille, Mr. Diyabanza seized an artifact from the Museum of African, Oceanic and Native American Arts in another live-streamed protest, before being halted by security. And earlier this month, in a third action that was also broadcast on Facebook, he and other activists took a Congolese funeral statue from the Afrika Museum in Berg en Dal, the Netherlands, before guards stopped him again.

Now, Mr. Diyabanza, the spokesman for a Pan-African movement that seeks reparations for colonialism, slavery and cultural expropriation, is set to stand trial in Paris on Sept. 30. Along with the four associates from the Quai Branly action, he will face a charge of attempted theft, in a case that is also likely to put France on the stand for its colonial track record and for holding so much of sub-Saharan Africa’s cultural heritage — 90,000 or so objects — in its museums.

“The fact that I had to pay my own money to see what had been taken by force, this heritage that belonged back home where I come from — that’s when the decision was made to take action,” said Mr. Diyabanza in an interview in Paris this month.

Describing the Quai Branly as “a museum that contains stolen objects,” he added, “There is no ban on an owner taking back his property the moment he comes across it.”

President Emmanuel Macron pledged in 2017 to give back much of Africa’s heritage held by France’s museums, and commissioned two academics to draw up a report on how to do it.

The 2018 report, by Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr, said any artifacts removed from sub-Saharan Africa in colonial times should be permanently returned if they were “taken by force, or presumed to be acquired through inequitable conditions,” and if their countries of origin asked for them.

More...

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/21/arts ... ogin-email

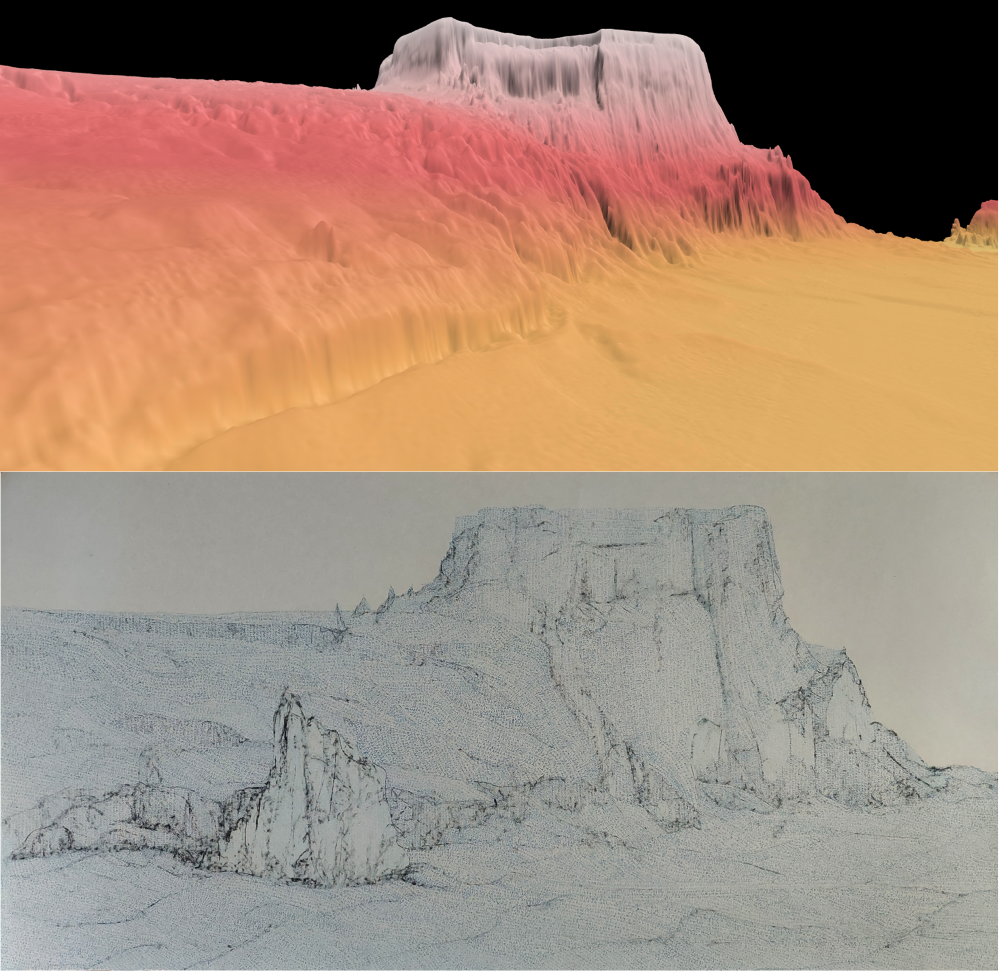

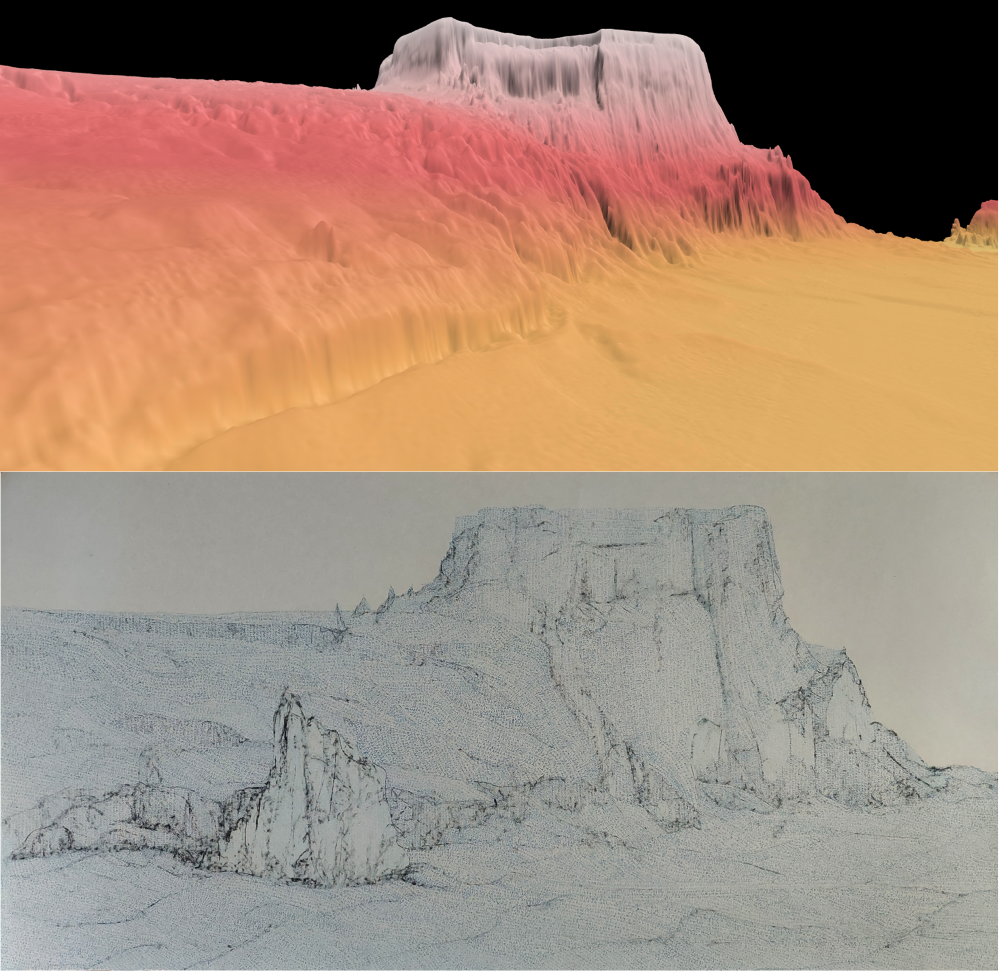

Black Monuments Matter

A Virtual Exhibition of Sub-Saharan Architecture

Presented by:

Zamani Project - University of Cape Town

Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations - Aga Khan University, London

Exhibition curators and organizers

Professor Stephane Pradines and Professor (emeritus) Dr. Heinz Rüther

The Aga Khan University Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations and the Zamani Project at the University of Cape Town are pleased to present the online exhibition “Black Monuments Matter”.

Black Monuments Matter recognises and highlights African contributions to world history by exhibiting World Heritage Monuments and architectural treasures from Sub-Saharan Africa.

In doing so, this exhibition sweeps away ideas based on racist theories and hopes to contribute to both awareness of African identity and pride of African Heritage. The exhibition is inspired by the “Black History Month” in the United Kingdom.

Black monuments matter and Black cultures matter. Sites and monuments are physical representations of histories, heritage, and developments in society. This exhibition aims to display the diversity and richness of African cultures as part of world history through the study of African Monuments; bringing awareness and pride of African roots and contributions to other cultures.

African cultures suffered extensively from slavery from the 16th to the 19th Century, and during the acceleration of European colonisation through the 19th and early 20th Century. Black Monuments Matter aspires to create links to living African heritage by making it visible, assessable, and known to as many people as possible.

In general, we would like to raise awareness of and respect towards Black cultures and Africa’s past to a larger audience. At the Aga Khan University, the University of Cape Town and the Zamani Project, we believe in the relevance and knowledge of cultures, and the importance of education towards its understanding and appreciation.

Through an approach founded on the latest knowledge and technology, this online exhibition offers visitors an opportunity to learn more about the glorious monuments and sites of African heritage and black cultures across Sub Saharan Africa.

The African continent has numerous sites and monuments of historic and cultural importance, and our exhibition showcases some of its diversity and richness. From the Pyramids of Sudan, the Great Mosque of Timbuktu, to the Swahili cities of East Africa, each site is presented in a virtual room and is introduced by short texts written by African scholars.

Many of Africa’s monuments are protected by UNESCO and have been given world heritage status. They are also protected and supported by national heritage authorities and by the support of international organisations such as the World Monument Fund and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

Our hope is that visitors to this exhibition will recognise and support the work of national and international organisations committed to the support of African heritage.

All the documentation presented in the exhibition are the result of many years of dedicated work by the Zamani team from the University of Cape Town in South Africa.

Access the exhibition at:

https://black-monuments-matter.zamaniproject.org/

A Virtual Exhibition of Sub-Saharan Architecture

Presented by:

Zamani Project - University of Cape Town

Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations - Aga Khan University, London

Exhibition curators and organizers

Professor Stephane Pradines and Professor (emeritus) Dr. Heinz Rüther

The Aga Khan University Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations and the Zamani Project at the University of Cape Town are pleased to present the online exhibition “Black Monuments Matter”.

Black Monuments Matter recognises and highlights African contributions to world history by exhibiting World Heritage Monuments and architectural treasures from Sub-Saharan Africa.

In doing so, this exhibition sweeps away ideas based on racist theories and hopes to contribute to both awareness of African identity and pride of African Heritage. The exhibition is inspired by the “Black History Month” in the United Kingdom.

Black monuments matter and Black cultures matter. Sites and monuments are physical representations of histories, heritage, and developments in society. This exhibition aims to display the diversity and richness of African cultures as part of world history through the study of African Monuments; bringing awareness and pride of African roots and contributions to other cultures.

African cultures suffered extensively from slavery from the 16th to the 19th Century, and during the acceleration of European colonisation through the 19th and early 20th Century. Black Monuments Matter aspires to create links to living African heritage by making it visible, assessable, and known to as many people as possible.

In general, we would like to raise awareness of and respect towards Black cultures and Africa’s past to a larger audience. At the Aga Khan University, the University of Cape Town and the Zamani Project, we believe in the relevance and knowledge of cultures, and the importance of education towards its understanding and appreciation.

Through an approach founded on the latest knowledge and technology, this online exhibition offers visitors an opportunity to learn more about the glorious monuments and sites of African heritage and black cultures across Sub Saharan Africa.

The African continent has numerous sites and monuments of historic and cultural importance, and our exhibition showcases some of its diversity and richness. From the Pyramids of Sudan, the Great Mosque of Timbuktu, to the Swahili cities of East Africa, each site is presented in a virtual room and is introduced by short texts written by African scholars.

Many of Africa’s monuments are protected by UNESCO and have been given world heritage status. They are also protected and supported by national heritage authorities and by the support of international organisations such as the World Monument Fund and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

Our hope is that visitors to this exhibition will recognise and support the work of national and international organisations committed to the support of African heritage.

All the documentation presented in the exhibition are the result of many years of dedicated work by the Zamani team from the University of Cape Town in South Africa.

Access the exhibition at:

https://black-monuments-matter.zamaniproject.org/

China Disappeared My Professor. It Can’t Silence His Poetry.

Against overwhelming state violence, poetry might appear to offer little recourse. But for many Uighurs, it’s a powerful form of resistance.

I last saw my old professor Abduqadir Jalalidin at his Urumqi apartment in late 2016. Over home-pulled laghman noodles and a couple of bottles of Chinese liquor, we talked and laughed about everything from Uighur literature to American politics. Several years earlier, when I had defended my master’s thesis on Uighur poetry, Jalalidin, himself a famous poet, had sat across from me and asked hard questions. Now we were just friends.

It was a memorable evening, one I’ve thought about many times since learning in early 2018 that Jalalidin had been sent, along with more than a million other Uighurs, to China’s internment camps.

As with my other friends and colleagues who have disappeared into this vast, secretive gulag, months stretched into years with no word from Jalalidin. And then, late this summer, the silence broke. Even in the camps, I learned, my old professor had continued writing poetry. Other inmates had committed his new poems to memory and had managed to transmit one of them beyond the camp gates.

In this forgotten place I have no lover’s touch

Each night brings darker dreams, I have no amulet

My life is all I ask, I have no other thirst

These silent thoughts torment, I have no way to hope

Who I once was, what I’ve become, I cannot know

Who could I tell my heart’s desires, I cannot say

My love, the temper of the fates I cannot guess

I long to go to you, I have no strength to move

Through cracks and crevices I’ve watched the seasons change

For news of you I’ve looked in vain to buds and flowers

To the marrow of my bones I’ve ached to be with you

What road led here, why do I have no road back home

Jalalidin’s poem is powerful testimony to a continuing catastrophe in China’s Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Since 2017, the Chinese state has swept a growing proportion of its Uighur population, along with other Muslim minorities, into an expanding system of camps, prisons and forced labor facilities. A mass sterilization campaign has targeted Uighur women, and the discovery of a multi-ton shipment of human hair from the region, most likely originating from the camps, evokes humanity’s darkest hours.

But my professor’s poem is also testimony to Uighurs’ unique use of poetry as a means of communal survival. Against overwhelming state violence, one might imagine that poetry would offer little recourse. Yet for many Uighurs — including those who risked sharing Jalalidin’s poem — poetry has a power and importance inconceivable in the American context.

Poetry permeates Uighur life. Influential cultural figures are often poets, and Uighurs of all backgrounds write poetry. Folk rhymes pepper everyday conversation — popular wisdom like “Don’t forget about your roots / keep the shine on your old boots” — and social media pulses with fresh verse on topics from unemployment to language preservation. Every Uighur knows the words of the poet Abdukhaliq, martyred by a Chinese warlord in 1933: “Awaken, poor Uighur, you’ve slept long enough…”

Uighurs have lived for a millennium at the crossroads of Eurasian civilizations, and their poetry draws on the artful concision of Turkic oral verse, the intricate meters of Persian poetry, and modernist currents from Europe, the Arab world and China. Oral and written forms intermingle in the work of contemporary Uighur poets like Adil Tuniyaz, while genres range from the classicism of my professor’s camp poem to the avant-garde iconoclasm of the Nothingist poets. (“A poem flies with the lonely owls that grant gloomy beauty to the night,” declared the exuberantly inscrutable 2009 Nothingism Manifesto.)

For generations, this vibrant poetic culture has allowed Uighurs to hone verse into a source of communal strength against colonization and repression. We can look back to the 19th century for an example: Sadir Palwan, a resistance fighter against the Qing empire, galvanized anti-imperial sentiment with the folk poems he spread by word of mouth. Imprisoned time and again, Sadir spun verses from his cell and during his multiple escapes, often bitterly satirizing the colonial authorities. “On the road to Küre, did your carriage break down, Magistrate? Having captured Sadir, is your heart content now, Magistrate?”

A century later, during the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976, when Uighur writers were imprisoned and their books burned, folk poets sustained their art by memory and word of mouth. Their work was instrumental in reviving Uighur culture in the 1980s, as large audiences once again gathered to hear their epic poems.

In the 2000s, Uighur anthropologist Rahile Dawut began recording these documents of collective memory, which provide grassroots perspectives on local history. In the Qumul region of eastern Xinjiang, for example, Dawut recorded an epic recounting a 17th-century insurrection against the Zunghar Mongols following their bloody conquest of Qumul. “Listen as I share the past,” sang a well-known Qumul folk poet before narrating the tragic story of Yachibeg, who led the rebellion to a string of victories before a local official betrayed him.

Dawut celebrated the richness and vitality of Uighur culture while remaining keenly aware of the pressures it continued to face. “Every time I went off on fieldwork,” she noted in a 2010 essay, “I would return from the ‘living museum’ of the people determined to gather even more material. Sadly, by the time I went back, these materials would be gone,” as local officials obstructed the performance and transmission of oral poetry. Dawut herself is now gone, detained since late 2017 along with many of Xinjiang University’s other Uighur professors.

Today, as the Chinese state bans Uighur books and paves over Muslim graveyards, poetry remains a powerful form of persistence and resistance for the Uighur people. Uighurs around the world are turning to poetry to grapple with the calamity in their homeland. “The target on my forehead / could not bring me to my knees,” wrote the exile poet Tahir Hamut Izgil from Washington in 2018.

Even as intellectuals in the Uighur diaspora chronicle the atrocities, most prominent Uighur intellectuals in Xinjiang — liberals and conservatives, devout Muslims and agnostics, party supporters and party critics — have already vanished into the camps as China escalates its campaign to extinguish Uighur identity.

But identity is a stubborn thing, as Uighur poet and novelist Perhat Tursun asserted in a well-known poem beginning with these defiant lines:

Like the waters of the Tarim

we began in this place

and we will finish here

We came from nowhere else

and we will not leave for anywhere

If God made humanity

God made us for this place

If man evolved from apes

we evolved from the apes of this place

For months after Tursun first posted this poem online over a decade ago, friends of mine in Urumqi would quote snatches of it by heart. In early 2018, as China’s purge of Uighur intellectuals widened, Tursun was sent to the camps. Yet his voice still reverberates: As I was writing this, I saw that a diaspora Uighur activist had posted Tursun’s poem to social media, where it continues to circulate widely.

The world has much to learn from a culture that has made art its antidote to authoritarianism. From behind the barbed wire and guard towers, my old professor has reminded us that we must not stand silently while that culture is annihilated.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/23/opin ... 778d3e6de3

Against overwhelming state violence, poetry might appear to offer little recourse. But for many Uighurs, it’s a powerful form of resistance.

I last saw my old professor Abduqadir Jalalidin at his Urumqi apartment in late 2016. Over home-pulled laghman noodles and a couple of bottles of Chinese liquor, we talked and laughed about everything from Uighur literature to American politics. Several years earlier, when I had defended my master’s thesis on Uighur poetry, Jalalidin, himself a famous poet, had sat across from me and asked hard questions. Now we were just friends.

It was a memorable evening, one I’ve thought about many times since learning in early 2018 that Jalalidin had been sent, along with more than a million other Uighurs, to China’s internment camps.

As with my other friends and colleagues who have disappeared into this vast, secretive gulag, months stretched into years with no word from Jalalidin. And then, late this summer, the silence broke. Even in the camps, I learned, my old professor had continued writing poetry. Other inmates had committed his new poems to memory and had managed to transmit one of them beyond the camp gates.

In this forgotten place I have no lover’s touch

Each night brings darker dreams, I have no amulet

My life is all I ask, I have no other thirst

These silent thoughts torment, I have no way to hope

Who I once was, what I’ve become, I cannot know

Who could I tell my heart’s desires, I cannot say

My love, the temper of the fates I cannot guess

I long to go to you, I have no strength to move

Through cracks and crevices I’ve watched the seasons change

For news of you I’ve looked in vain to buds and flowers

To the marrow of my bones I’ve ached to be with you

What road led here, why do I have no road back home

Jalalidin’s poem is powerful testimony to a continuing catastrophe in China’s Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region. Since 2017, the Chinese state has swept a growing proportion of its Uighur population, along with other Muslim minorities, into an expanding system of camps, prisons and forced labor facilities. A mass sterilization campaign has targeted Uighur women, and the discovery of a multi-ton shipment of human hair from the region, most likely originating from the camps, evokes humanity’s darkest hours.

But my professor’s poem is also testimony to Uighurs’ unique use of poetry as a means of communal survival. Against overwhelming state violence, one might imagine that poetry would offer little recourse. Yet for many Uighurs — including those who risked sharing Jalalidin’s poem — poetry has a power and importance inconceivable in the American context.

Poetry permeates Uighur life. Influential cultural figures are often poets, and Uighurs of all backgrounds write poetry. Folk rhymes pepper everyday conversation — popular wisdom like “Don’t forget about your roots / keep the shine on your old boots” — and social media pulses with fresh verse on topics from unemployment to language preservation. Every Uighur knows the words of the poet Abdukhaliq, martyred by a Chinese warlord in 1933: “Awaken, poor Uighur, you’ve slept long enough…”

Uighurs have lived for a millennium at the crossroads of Eurasian civilizations, and their poetry draws on the artful concision of Turkic oral verse, the intricate meters of Persian poetry, and modernist currents from Europe, the Arab world and China. Oral and written forms intermingle in the work of contemporary Uighur poets like Adil Tuniyaz, while genres range from the classicism of my professor’s camp poem to the avant-garde iconoclasm of the Nothingist poets. (“A poem flies with the lonely owls that grant gloomy beauty to the night,” declared the exuberantly inscrutable 2009 Nothingism Manifesto.)

For generations, this vibrant poetic culture has allowed Uighurs to hone verse into a source of communal strength against colonization and repression. We can look back to the 19th century for an example: Sadir Palwan, a resistance fighter against the Qing empire, galvanized anti-imperial sentiment with the folk poems he spread by word of mouth. Imprisoned time and again, Sadir spun verses from his cell and during his multiple escapes, often bitterly satirizing the colonial authorities. “On the road to Küre, did your carriage break down, Magistrate? Having captured Sadir, is your heart content now, Magistrate?”

A century later, during the Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976, when Uighur writers were imprisoned and their books burned, folk poets sustained their art by memory and word of mouth. Their work was instrumental in reviving Uighur culture in the 1980s, as large audiences once again gathered to hear their epic poems.

In the 2000s, Uighur anthropologist Rahile Dawut began recording these documents of collective memory, which provide grassroots perspectives on local history. In the Qumul region of eastern Xinjiang, for example, Dawut recorded an epic recounting a 17th-century insurrection against the Zunghar Mongols following their bloody conquest of Qumul. “Listen as I share the past,” sang a well-known Qumul folk poet before narrating the tragic story of Yachibeg, who led the rebellion to a string of victories before a local official betrayed him.

Dawut celebrated the richness and vitality of Uighur culture while remaining keenly aware of the pressures it continued to face. “Every time I went off on fieldwork,” she noted in a 2010 essay, “I would return from the ‘living museum’ of the people determined to gather even more material. Sadly, by the time I went back, these materials would be gone,” as local officials obstructed the performance and transmission of oral poetry. Dawut herself is now gone, detained since late 2017 along with many of Xinjiang University’s other Uighur professors.

Today, as the Chinese state bans Uighur books and paves over Muslim graveyards, poetry remains a powerful form of persistence and resistance for the Uighur people. Uighurs around the world are turning to poetry to grapple with the calamity in their homeland. “The target on my forehead / could not bring me to my knees,” wrote the exile poet Tahir Hamut Izgil from Washington in 2018.

Even as intellectuals in the Uighur diaspora chronicle the atrocities, most prominent Uighur intellectuals in Xinjiang — liberals and conservatives, devout Muslims and agnostics, party supporters and party critics — have already vanished into the camps as China escalates its campaign to extinguish Uighur identity.

But identity is a stubborn thing, as Uighur poet and novelist Perhat Tursun asserted in a well-known poem beginning with these defiant lines:

Like the waters of the Tarim

we began in this place

and we will finish here

We came from nowhere else

and we will not leave for anywhere

If God made humanity

God made us for this place

If man evolved from apes

we evolved from the apes of this place

For months after Tursun first posted this poem online over a decade ago, friends of mine in Urumqi would quote snatches of it by heart. In early 2018, as China’s purge of Uighur intellectuals widened, Tursun was sent to the camps. Yet his voice still reverberates: As I was writing this, I saw that a diaspora Uighur activist had posted Tursun’s poem to social media, where it continues to circulate widely.

The world has much to learn from a culture that has made art its antidote to authoritarianism. From behind the barbed wire and guard towers, my old professor has reminded us that we must not stand silently while that culture is annihilated.

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/23/opin ... 778d3e6de3

Toward an Optimistic New Architecture

Rebuilding, while a reminder of what’s been lost, is also a defiant act of hope.

When we were closing last year’s spring Design issue, it was the beginning of an era; now, 12 months later, we’re nearing its end. Of course, it’s not really the end, but on some days we’re able to pretend otherwise — we’re able to make plans again; we’re able to anticipate. Many of the crushing uncertainties we lived with for months have been answered (though in many cases, the answers are crushing, too).

March is always an unpredictable period in New York. There are days when you can feel the promise of not just spring but summer: The air becomes soft, the trees froth with green seemingly overnight and people gather outdoors on stoops and park benches in the relative warmth. The next day, though, the bone-chilling damp returns, or the whipping winds or, often, the snow. The month is not a transition between February and April so much as it is a combination of the two, the weather at its most fickle.

It also marks the return of twilight, with the sun lingering a little longer each day. Despite spending a significant part of my childhood in Hawaii, I’ve never been fond of the heat. But over this past year, I have grown to crave the sun, which feels like a bestowal. In a life spent largely indoors, the sun is a gift, a reassurance, a beckoning. An Italian fashion designer once pointed out to me that, unlike London, Milan and Paris, New York has bluebird days year-round; that combination of cold and sun is, he said, what he loves about the city. It is, he told me, a promise of hope.

The houses and buildings in this issue are also expressions of hope. This is perhaps most true of the civic structures (a school, a plaza, a church) designed by a number of Latin American architects in the aftermath of the 2017 earthquake that devastated the Mexican town of Jojutla. As Michael Snyder writes in his story, post-disaster reconstruction unites architects and governments to create projects that sometimes solve real, urgent problems ... but, often, can become exercises in self-indulgence and opportunities for grandstanding. In Jojutla, though, the architects tried to listen to the residents about their needs, as well as their aesthetic desires. The result is a collection of spaces that, as Snyder writes, may have been designed by outsiders, but now belong to the residents of Jojutla, who will eventually make them their own. “Over time,” he writes, “the buildings will reflect the community they serve, and the community may, in turn, be reshaped by the buildings, with fatalism and distrust slowly replaced by optimism for a future that need not repeat the present.”

Let this be the case for all of us: May fatalism and distrust be replaced by optimism. May we remember that the future need not repeat the present. And may we remember, too, that many things can be rebuilt — and that even if the world that emerges doesn’t resemble the one we knew, it is up to us to make it our own.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/15/t-ma ... iversified

Rebuilding, while a reminder of what’s been lost, is also a defiant act of hope.

When we were closing last year’s spring Design issue, it was the beginning of an era; now, 12 months later, we’re nearing its end. Of course, it’s not really the end, but on some days we’re able to pretend otherwise — we’re able to make plans again; we’re able to anticipate. Many of the crushing uncertainties we lived with for months have been answered (though in many cases, the answers are crushing, too).

March is always an unpredictable period in New York. There are days when you can feel the promise of not just spring but summer: The air becomes soft, the trees froth with green seemingly overnight and people gather outdoors on stoops and park benches in the relative warmth. The next day, though, the bone-chilling damp returns, or the whipping winds or, often, the snow. The month is not a transition between February and April so much as it is a combination of the two, the weather at its most fickle.

It also marks the return of twilight, with the sun lingering a little longer each day. Despite spending a significant part of my childhood in Hawaii, I’ve never been fond of the heat. But over this past year, I have grown to crave the sun, which feels like a bestowal. In a life spent largely indoors, the sun is a gift, a reassurance, a beckoning. An Italian fashion designer once pointed out to me that, unlike London, Milan and Paris, New York has bluebird days year-round; that combination of cold and sun is, he said, what he loves about the city. It is, he told me, a promise of hope.

The houses and buildings in this issue are also expressions of hope. This is perhaps most true of the civic structures (a school, a plaza, a church) designed by a number of Latin American architects in the aftermath of the 2017 earthquake that devastated the Mexican town of Jojutla. As Michael Snyder writes in his story, post-disaster reconstruction unites architects and governments to create projects that sometimes solve real, urgent problems ... but, often, can become exercises in self-indulgence and opportunities for grandstanding. In Jojutla, though, the architects tried to listen to the residents about their needs, as well as their aesthetic desires. The result is a collection of spaces that, as Snyder writes, may have been designed by outsiders, but now belong to the residents of Jojutla, who will eventually make them their own. “Over time,” he writes, “the buildings will reflect the community they serve, and the community may, in turn, be reshaped by the buildings, with fatalism and distrust slowly replaced by optimism for a future that need not repeat the present.”

Let this be the case for all of us: May fatalism and distrust be replaced by optimism. May we remember that the future need not repeat the present. And may we remember, too, that many things can be rebuilt — and that even if the world that emerges doesn’t resemble the one we knew, it is up to us to make it our own.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/15/t-ma ... iversified

Thank God for the Poets

Their words remind us that suffering is not our only birthright. Life is also our birthright — life and love and beauty.

NASHVILLE — When the poet Amanda Gorman stepped to the lectern at President Biden’s inauguration, she faced a much-diminished crowd of masked people on the National Mall, but she was speaking directly to the heart of a bruised nation:

Let the globe, if nothing else, say this is true:

That even as we grieved, we grew,

That even as we hurt, we hoped,

That even as we tired, we tried.

Ms. Gorman’s poem — addressed to “Americans, and the World” — was timeless in that way of the most necessary poems, but it was more than just timeless. After a year of losses both literal and figurative, she offered a salve that soothed, however briefly, our broken hearts and our broken age.

Poets have always given voice to our losses at times of national calamity. Walt Whitman’s “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d” is an elegy for Abraham Lincoln. Langston Hughes’s “Mississippi — 1955” came in direct response to the murder of Emmett Till. Denise Levertov wrote one poem after another after another to protest the war in Vietnam. In 2002, Billy Collins delivered a memorial poem for the victims of the Sept. 11 attacks before a special joint meeting of Congress.