Iran's Book House to review 'Diaries of Vladimir Ivanov'

According to IBNA correspondent, quoting from the Public Relations Office of Iran's Book House Institute, the organized to review 'Diaries of Vladimir Ivanov' is to be attended by the author Miklós Sárközy (PhD), and the Iranian experts Goudarz Rashtiani (PhD) and Mohsen Jafari-Mazhab (PhD).

'Diaries of Vladimir Ivanov' was edited by the Iranian scholar Farhad Daftary (PhD) and published in English in London, 2015.

Vladimir Ivanov was a noted Russian scholar who worked for a half a century on Ismaili studies in Iran and India has done. He found many texts related to this subject and made a consistent effort to edit, translate and publish these works.

The meeting is scheduled to be held at 4 to 6 p.m. in Iran's Book House Institute in Tehran.

http://www.ibna.ir/en/doc/naghli/232190 ... mir-ivanov

*****

Fifty Years in the East: The Memoirs of Wladimir IvanowHardcover– November 30, 2014

by Farhad Daftary(Editor)

http://www.amazon.com/Fifty-Years-East- ... 1784531529

Vladimir Ivanov

Today in history: The Ismaili Society was established

The Anjoman-e Esma‘ili (Ismaili Society), a research institution, was established on February 16, 1946 in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, under the patronage of Imam Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan III. The aim of the Society was to promote independent and critical studies of Ismailism.

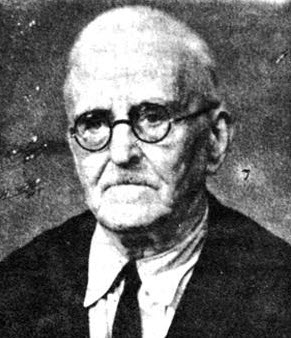

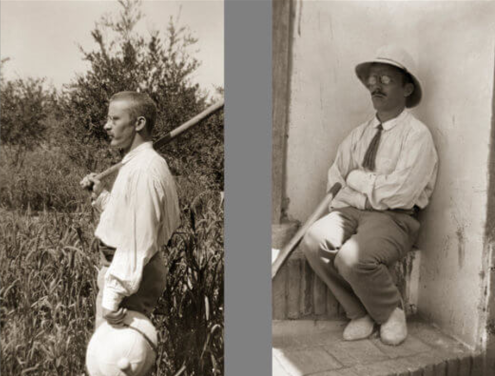

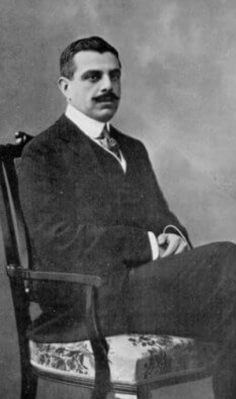

Vladimir Ivanow (Photo: Encyclopaedia Iranica)

Vladimir Ivanow (1886-1970) was instrumental in the establishment of the Ismaili Society, publishing a series of his works and collecting manuscripts. Over time, the Society came to possess a notable library of Ismaili manuscripts that are now in the library of The Institute of Ismaili Studies.

Born in St. Petersburg, Russia, Ivanow studied Arabic and Persian history as well as Islamic and Central Asian history at the Faculty of Oriental Languages, University of St. Petersburg, from where he graduated in 1911. He subsequently conducted field research on Persian dialects and folk poetry in Iran for many years.

In 1915, he joined the Asiatic Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg as an assistant keeper of the manuscript, where he catalogued a small number of Ismaili manuscripts acquired by Ivan Ivanovich Zarubin (1887-1964), the renowned Russian scholar of Tajik dialects. These manuscripts dated from the Alamut and post-Alamut periods of Nizari Ismaili history that had been preserved in Central Asia. This was Ivanow’s first contact with Ismaili literature.

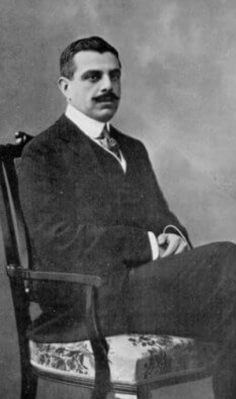

A guide to Ismaili literature by Ivanow (Photo: University of Toronto, Library Catalogue)

Ivanow settled in Calcutta, India, in 1920 where the president of the Asiatic Society of Bengal commissioned him to catalogue their extensive collection of Persian manuscripts. Subsequently Ivanow moved to Bombay, where he had established relations with Nizari Khojas who introduced him to Imam Sultan Mahomed Shah.

In January 1931, Imam Sultan Mahomed Shah employed Ivanow to conduct research into the literature and history of Ismailis. Ivanow found access to Ismaili manuscripts held in private collections in India, Persia, Afghanistan, Central Asia, and elsewhere. He also established relations with several scholars in this field who gave him access to their family collections of manuscripts dating to the Fatimid phases of Ismaili history. Ivanow described these manuscripts in his catalogue published in 1933, A Guide to Ismaili Literature, the first catalogue of the Ismaili sources published in modern times. This catalogue demonstrated the richness and diversity of Ismaili literature and was an invaluable tool, for several decades, in the advancement of Ismaili scholarship.

In a subsequent publication in 1963, Ivanow identified several hundred additional manuscripts. By this time, according to Daftary, “Ismaili studies as a whole had undergone a revolution, thanks to the concerted efforts of Ivanow and a few other notable scholars including A.A.A Fyzee (1899-1981), Husayn F. al-Hamdani (1901-1962), Zahed Ali (1888-1958) and Henry Corbin.”1

The Society’s latest publication and Ivanow’s final work, Ismaili Literature (Tehran, 1963), was a bibliographical survey of the extant Ismaili manuscript literature providing detailed information on some 900 titles. Ivanow identified, recovered, edited, translated and studied a large portion of the surviving literature of the Nizari Ismailis and stands as “the unrivalled founder of modern Nizari Ismaili studies.”2

/ismailimail.wordpress.com/2016/02/16/today-in-history-the-ismaili-society-was-established/

The Anjoman-e Esma‘ili (Ismaili Society), a research institution, was established on February 16, 1946 in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, under the patronage of Imam Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan III. The aim of the Society was to promote independent and critical studies of Ismailism.

Vladimir Ivanow (Photo: Encyclopaedia Iranica)

Vladimir Ivanow (1886-1970) was instrumental in the establishment of the Ismaili Society, publishing a series of his works and collecting manuscripts. Over time, the Society came to possess a notable library of Ismaili manuscripts that are now in the library of The Institute of Ismaili Studies.

Born in St. Petersburg, Russia, Ivanow studied Arabic and Persian history as well as Islamic and Central Asian history at the Faculty of Oriental Languages, University of St. Petersburg, from where he graduated in 1911. He subsequently conducted field research on Persian dialects and folk poetry in Iran for many years.

In 1915, he joined the Asiatic Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg as an assistant keeper of the manuscript, where he catalogued a small number of Ismaili manuscripts acquired by Ivan Ivanovich Zarubin (1887-1964), the renowned Russian scholar of Tajik dialects. These manuscripts dated from the Alamut and post-Alamut periods of Nizari Ismaili history that had been preserved in Central Asia. This was Ivanow’s first contact with Ismaili literature.

A guide to Ismaili literature by Ivanow (Photo: University of Toronto, Library Catalogue)

Ivanow settled in Calcutta, India, in 1920 where the president of the Asiatic Society of Bengal commissioned him to catalogue their extensive collection of Persian manuscripts. Subsequently Ivanow moved to Bombay, where he had established relations with Nizari Khojas who introduced him to Imam Sultan Mahomed Shah.

In January 1931, Imam Sultan Mahomed Shah employed Ivanow to conduct research into the literature and history of Ismailis. Ivanow found access to Ismaili manuscripts held in private collections in India, Persia, Afghanistan, Central Asia, and elsewhere. He also established relations with several scholars in this field who gave him access to their family collections of manuscripts dating to the Fatimid phases of Ismaili history. Ivanow described these manuscripts in his catalogue published in 1933, A Guide to Ismaili Literature, the first catalogue of the Ismaili sources published in modern times. This catalogue demonstrated the richness and diversity of Ismaili literature and was an invaluable tool, for several decades, in the advancement of Ismaili scholarship.

In a subsequent publication in 1963, Ivanow identified several hundred additional manuscripts. By this time, according to Daftary, “Ismaili studies as a whole had undergone a revolution, thanks to the concerted efforts of Ivanow and a few other notable scholars including A.A.A Fyzee (1899-1981), Husayn F. al-Hamdani (1901-1962), Zahed Ali (1888-1958) and Henry Corbin.”1

The Society’s latest publication and Ivanow’s final work, Ismaili Literature (Tehran, 1963), was a bibliographical survey of the extant Ismaili manuscript literature providing detailed information on some 900 titles. Ivanow identified, recovered, edited, translated and studied a large portion of the surviving literature of the Nizari Ismailis and stands as “the unrivalled founder of modern Nizari Ismaili studies.”2

/ismailimail.wordpress.com/2016/02/16/today-in-history-the-ismaili-society-was-established/

Meeting the Otherness: Wladimir Ivanow's Memoirs and his Early Encounters

with Iranian Minority Groups

Miklós Sárközy

https://www.cambridgescholars.com/download/sample/64460

Wladimir Alekseevich Ivanow1 (1886 – 1970) played a crucial role in the

development of Islamic science as a founding father of Ismaili studies. He

spent most of his life in exile in India and Iran (Persia) after 1917 due

to political reasons and – to a lesser extent – due to his own personal

decisions. His vast oeuvre in the field of Ismaili studies as well as his

contributions to Ismaili-related researches in Ismaili archaeology,

philology and history are milestones and are of great importance for those

interested in Ismaili studies and Shia history. His constant interest in

Ismailism successfully challenged the mainly Sunni-based scholarship of

Islamic studies in the first half of the 20th century. The present essay

aims at presenting hitherto neglected data on the beginnings of Ivanow's

scientific interests especially his earliest Ismaili connections before his

forced exile from Russia. It is perhaps a lesser known fact that besides

the Ismaili community, Ivanow published papers on other ethnic or religious

minorities such as the Roma of Iran (or as he called them: Gypsies) and

Sufis, which makes him an early pioneer of minority studies within the

field of Iranian studies. However, in the light of his long-awaited and

recently published personal memoirs, we can raise several new aspects

concerning his earliest contacts with these minority groups of Iran at the

dawn of his scientific career.

Read the whole article here:

https://www.cambridgescholars.com/download/sample/64460

with Iranian Minority Groups

Miklós Sárközy

https://www.cambridgescholars.com/download/sample/64460

Wladimir Alekseevich Ivanow1 (1886 – 1970) played a crucial role in the

development of Islamic science as a founding father of Ismaili studies. He

spent most of his life in exile in India and Iran (Persia) after 1917 due

to political reasons and – to a lesser extent – due to his own personal

decisions. His vast oeuvre in the field of Ismaili studies as well as his

contributions to Ismaili-related researches in Ismaili archaeology,

philology and history are milestones and are of great importance for those

interested in Ismaili studies and Shia history. His constant interest in

Ismailism successfully challenged the mainly Sunni-based scholarship of

Islamic studies in the first half of the 20th century. The present essay

aims at presenting hitherto neglected data on the beginnings of Ivanow's

scientific interests especially his earliest Ismaili connections before his

forced exile from Russia. It is perhaps a lesser known fact that besides

the Ismaili community, Ivanow published papers on other ethnic or religious

minorities such as the Roma of Iran (or as he called them: Gypsies) and

Sufis, which makes him an early pioneer of minority studies within the

field of Iranian studies. However, in the light of his long-awaited and

recently published personal memoirs, we can raise several new aspects

concerning his earliest contacts with these minority groups of Iran at the

dawn of his scientific career.

Read the whole article here:

https://www.cambridgescholars.com/download/sample/64460

Today in history: Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah established a research institution

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III (r. 1885-1957) established a research institution, the Ismaili Society (Anjoman-e Esma‘ili), on February 16, 1946 in Bombay (now Mumbai), India. According to the Charter, its primary objective was “the promotion of independent and critical study of all matters connected with Ismailism with the stated policy of refraining from all religio-political missionary activities” (Daftary, Anjoman-e Esma‘ili, IIS).

The Ismaili Society evolved from the Islamic Research Association also established by Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah in Bombay in 1933. The Russian scholar Wladimir Ivanow was involved in the creation of both institutions. Ivanow worked with his colleagues in the executive committee of the Association, notably its president Ali M. Mecklai and secretary Asaf A. A. Fyzee, to give an Ismaili focus to the research and publications of the Association and eventually transformed it into the new Ismaili Society, with Mecklai continuing as its president.

With Ivanow as editor and principal author, the Society established a series of texts in Persian, Arabic, English, and Gujarati. Ivanow’s close relations with non-Nizari Ismailis gave him access to carefully guarded private collections of Ismaili manuscripts, a large number of which he procured for the Society’s library.

Major publications

“Between 1946 and 1963 the Society published twenty-eight major items, twenty-two of which were contributed by Ivanow himself. The most important Ismaili texts, edited and translated for the first time by Ivanow include:

Nasir Khusraw’s Shish Fasl (Bombay, 1949);

Nasir al-Din Tusi’s Rawdat al-taslim (Bombay, 1950);

Pandiyat-i jawanmardi, containing the sayings of the late 15th century imam Mustansir bi’llah (Bombay, 1953);

Haft bab of Abu Ishaq Quhistani, a Nizari author of the early 16th century (Tehran, 1957);

Fasl dar bayan-i shenakht-i imam; the Tasnifat, attributed to Khayrkhah Herati, a Nizari missionary of the mid-16th century (Tehran, 1961);

and some works by Shihab al-Din Shah (d. 1884), the eldest son of Imam Aqa Ali Shah Aga Khan II.

The Society’s latest publication, and Ivanow’s final work, Ismaili Literature (Tehran, 1963), is a bibliography of the existing Ismaili manuscript literature providing detailed information on some 900 titles.

By 1964 the Society’s publication series was discontinued and the institution was absorbed by the Ismaili Association of Pakistan in Karachi. The Institute of Ismaili Studies is now the steward of the Ismaili Society’s collection of manuscripts.

Adapted from

Dr. Farhad Daftary’s, Anjoman-e-Esma’ili (Isma’ili Society, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/02/16/the-ismaili-society-was-established-in-bombay-by-imam-sultan-muhammad-shah/?utm_source=Direct

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III (r. 1885-1957) established a research institution, the Ismaili Society (Anjoman-e Esma‘ili), on February 16, 1946 in Bombay (now Mumbai), India. According to the Charter, its primary objective was “the promotion of independent and critical study of all matters connected with Ismailism with the stated policy of refraining from all religio-political missionary activities” (Daftary, Anjoman-e Esma‘ili, IIS).

The Ismaili Society evolved from the Islamic Research Association also established by Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah in Bombay in 1933. The Russian scholar Wladimir Ivanow was involved in the creation of both institutions. Ivanow worked with his colleagues in the executive committee of the Association, notably its president Ali M. Mecklai and secretary Asaf A. A. Fyzee, to give an Ismaili focus to the research and publications of the Association and eventually transformed it into the new Ismaili Society, with Mecklai continuing as its president.

With Ivanow as editor and principal author, the Society established a series of texts in Persian, Arabic, English, and Gujarati. Ivanow’s close relations with non-Nizari Ismailis gave him access to carefully guarded private collections of Ismaili manuscripts, a large number of which he procured for the Society’s library.

Major publications

“Between 1946 and 1963 the Society published twenty-eight major items, twenty-two of which were contributed by Ivanow himself. The most important Ismaili texts, edited and translated for the first time by Ivanow include:

Nasir Khusraw’s Shish Fasl (Bombay, 1949);

Nasir al-Din Tusi’s Rawdat al-taslim (Bombay, 1950);

Pandiyat-i jawanmardi, containing the sayings of the late 15th century imam Mustansir bi’llah (Bombay, 1953);

Haft bab of Abu Ishaq Quhistani, a Nizari author of the early 16th century (Tehran, 1957);

Fasl dar bayan-i shenakht-i imam; the Tasnifat, attributed to Khayrkhah Herati, a Nizari missionary of the mid-16th century (Tehran, 1961);

and some works by Shihab al-Din Shah (d. 1884), the eldest son of Imam Aqa Ali Shah Aga Khan II.

The Society’s latest publication, and Ivanow’s final work, Ismaili Literature (Tehran, 1963), is a bibliography of the existing Ismaili manuscript literature providing detailed information on some 900 titles.

By 1964 the Society’s publication series was discontinued and the institution was absorbed by the Ismaili Association of Pakistan in Karachi. The Institute of Ismaili Studies is now the steward of the Ismaili Society’s collection of manuscripts.

Adapted from

Dr. Farhad Daftary’s, Anjoman-e-Esma’ili (Isma’ili Society, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/02/16/the-ismaili-society-was-established-in-bombay-by-imam-sultan-muhammad-shah/?utm_source=Direct

[Feb]This month in history: The pioneer of Ismaili studies, Ivanow, came into contact with Ismailis for the first time

Posted by Nimira Dewji

“They [Ismailis] with amazing care and devotion kept through ages burning that Light, mentioned in the Qur’an which God always protects against all attempts of His enemies to extinguish it…I rarely saw anything so extraordinary and impressive as this ancient tradition being devoutly preserved…”

Ivanow

Ivanow. Source: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

The pioneer of Ismailis Studies, Vladmir Ivanow was born in 1886 in St. Petersburg, Russia, where he studied Arabic and Persian as well as Islamic and Central Asian history at the Faculty of Oriental Languages, University of St. Petersburg, graduating in 1911.

During his travels in Persia in 1912, where he conducted field research on Persian dialects and folk poetry, Ivanow heard about a community called Ismailis, but he disbelieved it. At the time, it was universally accepted that Ismailis of Alamut (1090-1256) in Persia had been wiped out by the brutality of the Mongols. Upon further investigation, Ivanow confirmed the existence of Ismailis in various localities in Persia, encountering many of them. He stated:

“I came in touch with the Ismailis for the first time in Persia, in February 1912 […] My learned friends in Europe plainly disbelieved me when I wrote about the community to them. It appeared to them quite unbelievable that the most brutal persecution, wholesale slaughter, age-long hostility and suppression were unable to annihilate the community which even at its highest formed but a small minority in the country…

Only later on, however, when my contact with them grew more intimate, I was able to see the reasons for such surprising vitality. It was their quite extraordinary devotion and faithfulness to the tradition of their ancestors, the ungrudging patience with which they suffered all the calamities and misfortunes, cherishing no illusions whatsoever as to what they could expect in life and in the contact with their majority fellow countrymen. They with amazing care and devotion kept through ages burning that Light, mentioned in the Qur’an which God always protects against all attempts of His enemies to extinguish it. I rarely saw anything so extraordinary and impressive as this ancient tradition being devoutly preserved in the poor muddy huts of mountain hamlets or poor villages in the desert” (My First Meeting with the Ismailis in Persia, IIS).

In 1915, Ivanow joined the Asiatic Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg as an assistant keeper of manuscripts. Ivanow catalogued a small number of Ismaili manuscripts, his first contact with Ismaili literature, acquired by Ivan Zarubin (1887-1964), the renowned Russian scholar of Tajik dialects. These manuscripts, dating to the Alamut (1090-1256) and post-Alamut periods of Nizari Ismaili history, had been preserved in Central Asia.

Ivanow settled in Calcutta, India, in 1920 where the president of the Asiatic Society of Bengal commissioned him to catalogue their extensive collection of Persian manuscripts. Subsequently Ivanow moved to Bombay (Mumbai), where he had established relations with Nizari Khojas who introduced him to Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah.

In January 1931, Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah employed Ivanow to conduct research into the literature and history of Ismailis. Ivanow found access to Ismaili manuscripts held in private collections in India, Persia, Afghanistan, Central Asia, and elsewhere. He also established relations with several scholars in this field who gave him access to their family collections of manuscripts dating to the Fatimid phase of Ismaili history. Ivanow described these manuscripts in his catalogue published in 1933, A Guide to Ismaili Literature, the first catalogue of the Ismaili sources published in modern times, demonstrating the richness and diversity of Ismaili literature.

Ivanow Persia Ismailis

A guide to Ismaili Literature by Ivanow. Source: University of Toronto Library Catalogue

In a subsequent publication in 1963, Ivanow identified several hundred additional manuscripts. By this time, according to Daftary, “Ismaili studies as a whole had undergone a revolution,” due to the efforts of Ivanow and a few other notable scholars including A.A.A Fyzee (1899-1981), Husayn F. al-Hamdani (1901-1962), Zahed Ali (1888-1958), and Henry Corbin (1903-1978).

The Society’s latest publication and Ivanow’s final work, Ismaili Literature (Tehran, 1963), was a bibliographical survey of the existing Ismaili manuscript literature, providing detailed information on some 900 titles. Ivanow identified, recovered, edited, and translated a large portion of the surviving literature of the Nizari Ismailis, spending the last decade of his life in Tehran where he died in 1970 and was buried. In the words of Daftary, Ivanow “stands as the unrivalled founder of modern Nizari Ismail studies.”

Sources:

Ivanow, My First Meeting with the Ismailis in Persia, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Dr Farhad Daftary, Anjoman-e Esma‘ili (lsma‘ili Society), The Institute of Ismaili Studies

https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/ ... st-time-2/

Posted by Nimira Dewji

“They [Ismailis] with amazing care and devotion kept through ages burning that Light, mentioned in the Qur’an which God always protects against all attempts of His enemies to extinguish it…I rarely saw anything so extraordinary and impressive as this ancient tradition being devoutly preserved…”

Ivanow

Ivanow. Source: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

The pioneer of Ismailis Studies, Vladmir Ivanow was born in 1886 in St. Petersburg, Russia, where he studied Arabic and Persian as well as Islamic and Central Asian history at the Faculty of Oriental Languages, University of St. Petersburg, graduating in 1911.

During his travels in Persia in 1912, where he conducted field research on Persian dialects and folk poetry, Ivanow heard about a community called Ismailis, but he disbelieved it. At the time, it was universally accepted that Ismailis of Alamut (1090-1256) in Persia had been wiped out by the brutality of the Mongols. Upon further investigation, Ivanow confirmed the existence of Ismailis in various localities in Persia, encountering many of them. He stated:

“I came in touch with the Ismailis for the first time in Persia, in February 1912 […] My learned friends in Europe plainly disbelieved me when I wrote about the community to them. It appeared to them quite unbelievable that the most brutal persecution, wholesale slaughter, age-long hostility and suppression were unable to annihilate the community which even at its highest formed but a small minority in the country…

Only later on, however, when my contact with them grew more intimate, I was able to see the reasons for such surprising vitality. It was their quite extraordinary devotion and faithfulness to the tradition of their ancestors, the ungrudging patience with which they suffered all the calamities and misfortunes, cherishing no illusions whatsoever as to what they could expect in life and in the contact with their majority fellow countrymen. They with amazing care and devotion kept through ages burning that Light, mentioned in the Qur’an which God always protects against all attempts of His enemies to extinguish it. I rarely saw anything so extraordinary and impressive as this ancient tradition being devoutly preserved in the poor muddy huts of mountain hamlets or poor villages in the desert” (My First Meeting with the Ismailis in Persia, IIS).

In 1915, Ivanow joined the Asiatic Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg as an assistant keeper of manuscripts. Ivanow catalogued a small number of Ismaili manuscripts, his first contact with Ismaili literature, acquired by Ivan Zarubin (1887-1964), the renowned Russian scholar of Tajik dialects. These manuscripts, dating to the Alamut (1090-1256) and post-Alamut periods of Nizari Ismaili history, had been preserved in Central Asia.

Ivanow settled in Calcutta, India, in 1920 where the president of the Asiatic Society of Bengal commissioned him to catalogue their extensive collection of Persian manuscripts. Subsequently Ivanow moved to Bombay (Mumbai), where he had established relations with Nizari Khojas who introduced him to Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah.

In January 1931, Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah employed Ivanow to conduct research into the literature and history of Ismailis. Ivanow found access to Ismaili manuscripts held in private collections in India, Persia, Afghanistan, Central Asia, and elsewhere. He also established relations with several scholars in this field who gave him access to their family collections of manuscripts dating to the Fatimid phase of Ismaili history. Ivanow described these manuscripts in his catalogue published in 1933, A Guide to Ismaili Literature, the first catalogue of the Ismaili sources published in modern times, demonstrating the richness and diversity of Ismaili literature.

Ivanow Persia Ismailis

A guide to Ismaili Literature by Ivanow. Source: University of Toronto Library Catalogue

In a subsequent publication in 1963, Ivanow identified several hundred additional manuscripts. By this time, according to Daftary, “Ismaili studies as a whole had undergone a revolution,” due to the efforts of Ivanow and a few other notable scholars including A.A.A Fyzee (1899-1981), Husayn F. al-Hamdani (1901-1962), Zahed Ali (1888-1958), and Henry Corbin (1903-1978).

The Society’s latest publication and Ivanow’s final work, Ismaili Literature (Tehran, 1963), was a bibliographical survey of the existing Ismaili manuscript literature, providing detailed information on some 900 titles. Ivanow identified, recovered, edited, and translated a large portion of the surviving literature of the Nizari Ismailis, spending the last decade of his life in Tehran where he died in 1970 and was buried. In the words of Daftary, Ivanow “stands as the unrivalled founder of modern Nizari Ismail studies.”

Sources:

Ivanow, My First Meeting with the Ismailis in Persia, The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Dr Farhad Daftary, Anjoman-e Esma‘ili (lsma‘ili Society), The Institute of Ismaili Studies

https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2020/ ... st-time-2/

Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah employed Ivanow to research the history, philosophy, and literature of Ismailis

Posted by Nimira Dewji

Mawlana Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III (r. 1885-1957) established a research institution, the Ismaili Society, in 1946 in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, for the study of all matters connected with Ismailism. Imam employed Wladimir Ivanow (1886-1970), the pioneer of modern Ismail studies, to undertake this task. On 1 January 1931 Ivanow began working at the Ismaili Society.

(About Ivanow and the Ismaili Society)

In his autobiography, Fifty Years in the East, Ivanow describes his experience:

“In December, I was informed that His Highness the Aga Khan [III] had consented to my engagement in regular research on the history, literature, and philosophy of Ismailism. Aga Khan III, a man of creative mind and excellent education…realised the harmful effects of retaining traditional secrecy in modern times and therefore abolished it (Fifty Years in the East p 165).

I was certainly very glad and at the end of December I left via Hyderabad for Bombay, where I started my work … First of all, I started looking for Ismaili works. The Khojas had some religious books in Gujarati and other languages which I did not know. They had no such works in Arabic, and possessed only two Persian manuscripts… Fortunately, I received money for the purchase of Arabic Ismaili manuscripts from the Bohras, and Persian books from the Badakhshani and Persian (Nizari Ismaili) pilgrims, who came to Bombay for the ceremony of the didar of their Imam.

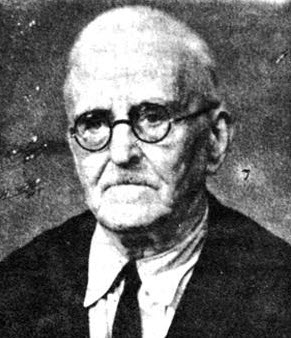

Imam Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III. Image: Aga Khan Centre

My ‘breakthrough’ in the entanglement of traditional Ismaili secrecy and direct access to their genuine literature undoubtedly constituted an important step in the development of Islamic studies and the study of Ismailism…. During my only conversation with the late Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan, concerning the programme of my research he emphasised that I should concentrate on the history of his ancestors. He recalled the well-known fact that his grandfather, Hasan Ali Shah [r.1817-1881], the original Aga Khan, was attacked in Sind by Baluchi brigands… He himself escaped almost by miracle. His property, including precious books belonging to the family was pillaged… (Ibid. p 83-88).

I succeeded in finding a number of persons who possessed them [Ismaili manuscripts], among both the Khoja and Bohra Ismailis. The most valuable contact was an old man, a retired servant of the late Aga Khan, Musa Khan Khorasani (d. 1937). [He] was a bibliophile and collector of Ismaili manuscripts, whose Persian ancestors had accompanied Hasan Ali Shah, Aga Khan I, from Persia to India in the early 1840s. The family had remained in the service of the Ismaili Imams… he made his collection accessible to me and allowed me to copy and photograph his books. This Musa Khan wrote a legendary history of Ismailism…

A young and wealthy Khoja businessman, Ismaili Mohammed Jafer, offered to meet the printing costs of the edited versions of Musa Khan’s manuscripts. However, the matter appeared to be rather complicated because of the hostility of some reactionary circles. It was decided that the best way forward would be to offer them for publication to a recognized academic institution, such as the Bombay branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, which was founded at the beginning of the 19th century. It published a journal, memoirs and a separate series of academic works…. (Ibid. p 90).

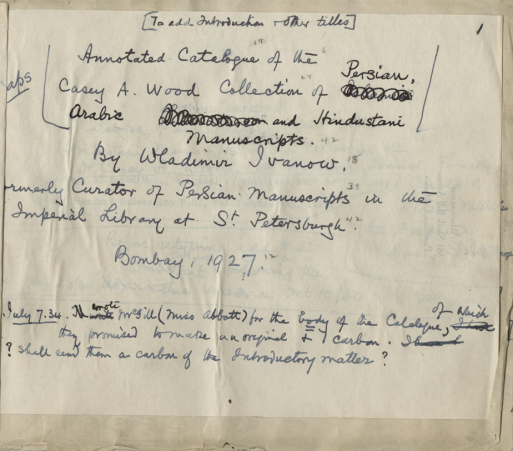

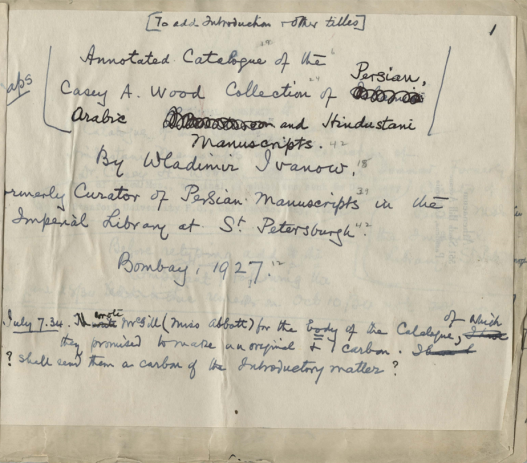

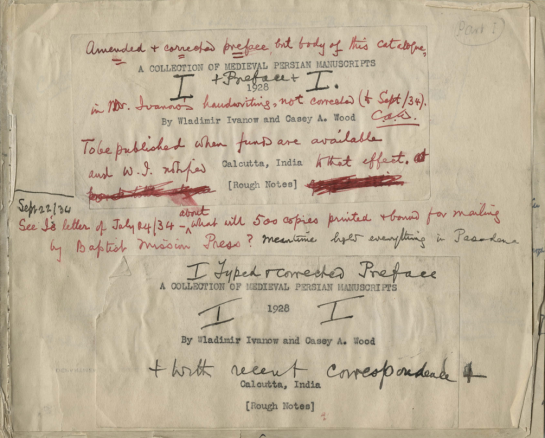

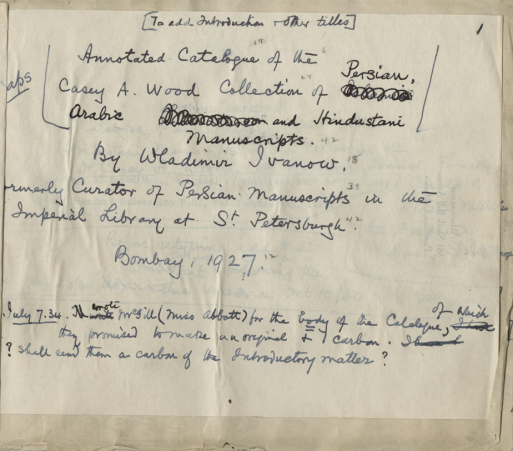

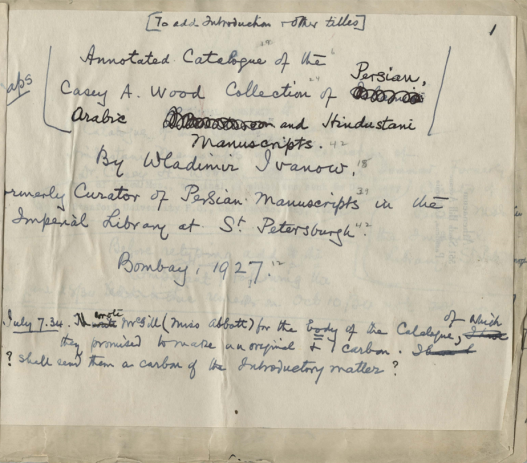

Wladimir’s handwritten catalogue preceded by a typescript title page labelled “rough notes.” Image: Annotated catalogue of the Casey A. Wood Collection of Persian, Arabic, and Hindustani manuscripts; Severson, The Dark Room, McGill Digitized Library

My friend Asaf A.A. Fyzee, a young advocate educated at the University of Cambridge, was the secretary of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. We requested that he discuss our proposal at the meeting of their Council. It was submitted, put to vote, and rejected. One of the members of the Council, a retired Hindu official, had assured his colleagues that the proposal should be turned down because of they published the books, the Aga Khan might send his ‘assassins’ to murder them all. This evoked protests and a learned Parsi said although such a things was certainly quite improbable, he advised that the proposal and the grant money for it should be rejected because publication of such books might provoke street riots. All this now seems ridiculous, but it demonstrated what even the most educated people were then capable of believing.” (Ibid. p 91-92).

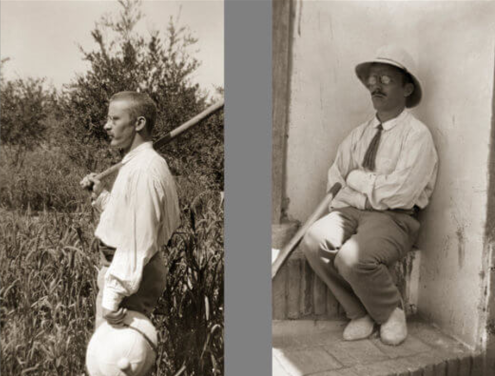

Young Ivanow in India. Images: Aga Khan Centre

I suggested founding an entirely new organization under a neutral name, with no mention of Ismailism, that could publish our books under its auspices. So, after some discussion, the ‘Islamic Research Association’ was born.

The Association was formally founded in February 1933 with headquarters in Bombay. … Aga Khan III was the Association’s patron. By 1938, the membership of the Association stood at 83…

Unfortunately, misunderstanding gradually cropped up again. From my point of view, the most important matter was the publication of genuine Ismaili works, but to some members of the organizing group this appeared to be of secondary importance. They were more concerned with public images and all theatricals of meetings, gatherings and speeches. And I remained the only worker [i.e. working scholar]. It was mentioned that the publication of further Ismaili works would turn the [Association’s] series into ‘Ivanow’s Ismaili Series.’ The argument went like this: ‘It was necessary to publish some non-Ismaili works, by another author, especially in Urdu – otherwise God only knows what people would think.’ I felt repelled by this behavior and, from early on, started to distance myself from the newly born body.

Having published five works, I prepared a new book for publication dealing with one of the most cardinal and difficult questions in the study of Ismaili history, namely the real role of Abd Allah ibn Maymun al-Qaddah, a companion of the early Shi’i Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq (d. 765) and reporter of numerous hadiths from him. This respected non-Alid personality, who was a Shi’I traditionalist from the Hijaz and died sometime during the second half of the 8th century, is introduced into anti-Ismaili polemics starting with Ibn Rizam, who flourished in Baghdad in the first half of the 10th century and wrote a major work around 951 in refutation of the Ismailis …. As a result, Ismailism was depicted as an arch-heresy designed to destroy Islam from within, and the Alid genealogy of the early Ismaili Imams and the Fatimid Imam-caliphs was also refuted (Ibid. p 93 n. 94).

When the book was ready I gave it for review to two members of the ‘organising group,’ as was stipulated by the home-made ‘constitution,’ and at a subsequent meeting I offered to send the manuscript for printing. But one of the group members, a non-worker himself, suggested giving the book to professor so-and-so for their approval. In fact, none of the suggested scholars had anything to do with Ismailsim, and it would have been a plain formality and waste of time, pure procrastination so dear to the bureaucratic mentality of the Indians. I became furious and told them that either the manuscript should be posted the next day or I would leave their Association.

They tried to change my mind, but I was fed up with all this and left. This Association still exists, but in a state of hibernation. In the last 14 years they have not published anything, although they still have some funds…

I suggested to the President of the Association, Mr Ali Mahomed Mecklai, to start a new and independent organization for the continuation of Ismaili publications, but this time without masking its real purpose and calling it the ‘Ismaili Society.’ Its membership was based on a number of principles, and would be open only to active researchers of Ismailism and not to the general public. Only those who had at least one published study of Ismailism could be eligible for membership. The proposal was approved and on 6 February 1946 the Ismaili Society was born. Invitations to join were circulated among those eligible and 25 scholars were originally elected as members…. Syrian and Egyptians have been the most industrious members, as for them Ismailism is part of their own history and heritage. But this is not the case in Persia and India. Since Arab and Persian Ismailis suffer from the want of literature on Ismailism, they willingly buy the most worthless booklets from commercial publishers…. During the last 22 years, the [Ismaili] Society has published 28 works in three series…

We also experimented with publishing a non-periodical collection of articles… But it was discontinued because of the shortage of contributors. And still the most important task remains the preparation of critical editions of genuine Ismaili texts. The difficulties are almost insurmountable. Ever since the beginning of this work, I have done everything possible to invite and encourage additional contributors from amongst educated Persians and Arabs. But I have failed completely. .. No one wanted to work for the advancement of knowledge, and even for future monetary gain, but everyone demanded cash, and too much cash, which is not so easy to obtain” (Ibid. p 94-95).

In July 1948, I attended the 21st Congress of Orientalists in Paris, representing the Ismaili Society… In April 1954, I was invited by the Persian government to attend the celebrations of the 900th anniversary of the birth of Avicenna [Ibn Sina], in Tehran and Hamdan. … I also took the opportunity to make some arrangements for my planned work in Alamut and Lamasar where I spent two seasons in 1957 and 1958. This was made possible through a generous grant of £350 contributed by the Khojas of East Africa.”

Fifty Years in the East, The Memoirs of Wladimir Ivanow, Ed. Farhad Daftary, I.B. Tauris, London, 2015

Alamut Ismailis

Remains of fortifications on Alamut rock. Image: Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest. Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria.

Lamasar was the last of the fortresses to fall to the Mongols. Image: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

(More on Ismaili State of Alamut https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2021/ ... -alamut-2/ [1090-1256])

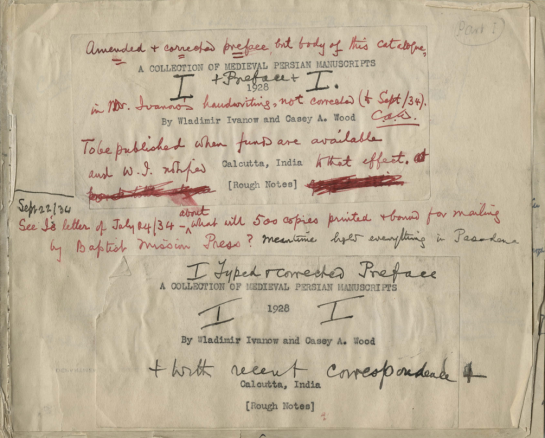

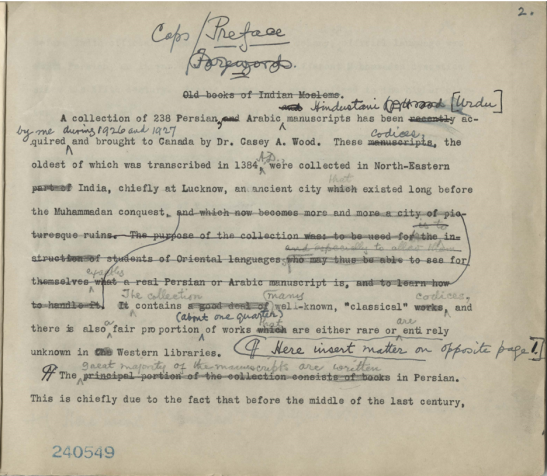

The revised title page dated Bombay, 1927; the “rough notes” title page is dated Calcutta, India, 1928 and has Wood’s manuscript notations re publication possibilities dated 1934. Image: Annotated catalogue of the Casey A. Wood Collection of Persian, Arabic, and Hindustani manuscripts; Sarah Severson/The Dark Room, McGill Digitized Library

The revised title page is dated: Bombay, 1927; the “rough notes” title page is dated Calcutta, India, 1928 and has Wood’s manuscript notations re publication possibilities dated 1934. Image: Annotated Catalogue of the Casey A. Wood; Sarah Severson/The Dark Room, McGill Digitized Library

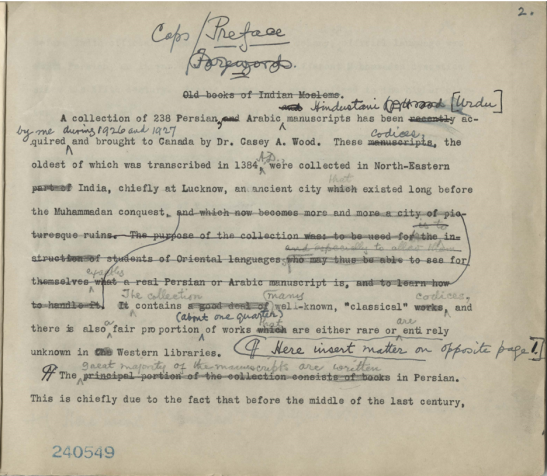

A handwritten and a typescript manuscript. Image: Annotated catalogue of the Casey A. Wood Collection of Persian, Arabic, and Hindustani manuscripts; Sarah Severson/The Dark Room, McGill Digitized Library

https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2021/ ... -ismailis/

Posted by Nimira Dewji

Mawlana Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III (r. 1885-1957) established a research institution, the Ismaili Society, in 1946 in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, for the study of all matters connected with Ismailism. Imam employed Wladimir Ivanow (1886-1970), the pioneer of modern Ismail studies, to undertake this task. On 1 January 1931 Ivanow began working at the Ismaili Society.

(About Ivanow and the Ismaili Society)

In his autobiography, Fifty Years in the East, Ivanow describes his experience:

“In December, I was informed that His Highness the Aga Khan [III] had consented to my engagement in regular research on the history, literature, and philosophy of Ismailism. Aga Khan III, a man of creative mind and excellent education…realised the harmful effects of retaining traditional secrecy in modern times and therefore abolished it (Fifty Years in the East p 165).

I was certainly very glad and at the end of December I left via Hyderabad for Bombay, where I started my work … First of all, I started looking for Ismaili works. The Khojas had some religious books in Gujarati and other languages which I did not know. They had no such works in Arabic, and possessed only two Persian manuscripts… Fortunately, I received money for the purchase of Arabic Ismaili manuscripts from the Bohras, and Persian books from the Badakhshani and Persian (Nizari Ismaili) pilgrims, who came to Bombay for the ceremony of the didar of their Imam.

Imam Sir Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan III. Image: Aga Khan Centre

My ‘breakthrough’ in the entanglement of traditional Ismaili secrecy and direct access to their genuine literature undoubtedly constituted an important step in the development of Islamic studies and the study of Ismailism…. During my only conversation with the late Sultan Muhammad Shah Aga Khan, concerning the programme of my research he emphasised that I should concentrate on the history of his ancestors. He recalled the well-known fact that his grandfather, Hasan Ali Shah [r.1817-1881], the original Aga Khan, was attacked in Sind by Baluchi brigands… He himself escaped almost by miracle. His property, including precious books belonging to the family was pillaged… (Ibid. p 83-88).

I succeeded in finding a number of persons who possessed them [Ismaili manuscripts], among both the Khoja and Bohra Ismailis. The most valuable contact was an old man, a retired servant of the late Aga Khan, Musa Khan Khorasani (d. 1937). [He] was a bibliophile and collector of Ismaili manuscripts, whose Persian ancestors had accompanied Hasan Ali Shah, Aga Khan I, from Persia to India in the early 1840s. The family had remained in the service of the Ismaili Imams… he made his collection accessible to me and allowed me to copy and photograph his books. This Musa Khan wrote a legendary history of Ismailism…

A young and wealthy Khoja businessman, Ismaili Mohammed Jafer, offered to meet the printing costs of the edited versions of Musa Khan’s manuscripts. However, the matter appeared to be rather complicated because of the hostility of some reactionary circles. It was decided that the best way forward would be to offer them for publication to a recognized academic institution, such as the Bombay branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, which was founded at the beginning of the 19th century. It published a journal, memoirs and a separate series of academic works…. (Ibid. p 90).

Wladimir’s handwritten catalogue preceded by a typescript title page labelled “rough notes.” Image: Annotated catalogue of the Casey A. Wood Collection of Persian, Arabic, and Hindustani manuscripts; Severson, The Dark Room, McGill Digitized Library

My friend Asaf A.A. Fyzee, a young advocate educated at the University of Cambridge, was the secretary of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. We requested that he discuss our proposal at the meeting of their Council. It was submitted, put to vote, and rejected. One of the members of the Council, a retired Hindu official, had assured his colleagues that the proposal should be turned down because of they published the books, the Aga Khan might send his ‘assassins’ to murder them all. This evoked protests and a learned Parsi said although such a things was certainly quite improbable, he advised that the proposal and the grant money for it should be rejected because publication of such books might provoke street riots. All this now seems ridiculous, but it demonstrated what even the most educated people were then capable of believing.” (Ibid. p 91-92).

Young Ivanow in India. Images: Aga Khan Centre

I suggested founding an entirely new organization under a neutral name, with no mention of Ismailism, that could publish our books under its auspices. So, after some discussion, the ‘Islamic Research Association’ was born.

The Association was formally founded in February 1933 with headquarters in Bombay. … Aga Khan III was the Association’s patron. By 1938, the membership of the Association stood at 83…

Unfortunately, misunderstanding gradually cropped up again. From my point of view, the most important matter was the publication of genuine Ismaili works, but to some members of the organizing group this appeared to be of secondary importance. They were more concerned with public images and all theatricals of meetings, gatherings and speeches. And I remained the only worker [i.e. working scholar]. It was mentioned that the publication of further Ismaili works would turn the [Association’s] series into ‘Ivanow’s Ismaili Series.’ The argument went like this: ‘It was necessary to publish some non-Ismaili works, by another author, especially in Urdu – otherwise God only knows what people would think.’ I felt repelled by this behavior and, from early on, started to distance myself from the newly born body.

Having published five works, I prepared a new book for publication dealing with one of the most cardinal and difficult questions in the study of Ismaili history, namely the real role of Abd Allah ibn Maymun al-Qaddah, a companion of the early Shi’i Imam Ja’far al-Sadiq (d. 765) and reporter of numerous hadiths from him. This respected non-Alid personality, who was a Shi’I traditionalist from the Hijaz and died sometime during the second half of the 8th century, is introduced into anti-Ismaili polemics starting with Ibn Rizam, who flourished in Baghdad in the first half of the 10th century and wrote a major work around 951 in refutation of the Ismailis …. As a result, Ismailism was depicted as an arch-heresy designed to destroy Islam from within, and the Alid genealogy of the early Ismaili Imams and the Fatimid Imam-caliphs was also refuted (Ibid. p 93 n. 94).

When the book was ready I gave it for review to two members of the ‘organising group,’ as was stipulated by the home-made ‘constitution,’ and at a subsequent meeting I offered to send the manuscript for printing. But one of the group members, a non-worker himself, suggested giving the book to professor so-and-so for their approval. In fact, none of the suggested scholars had anything to do with Ismailsim, and it would have been a plain formality and waste of time, pure procrastination so dear to the bureaucratic mentality of the Indians. I became furious and told them that either the manuscript should be posted the next day or I would leave their Association.

They tried to change my mind, but I was fed up with all this and left. This Association still exists, but in a state of hibernation. In the last 14 years they have not published anything, although they still have some funds…

I suggested to the President of the Association, Mr Ali Mahomed Mecklai, to start a new and independent organization for the continuation of Ismaili publications, but this time without masking its real purpose and calling it the ‘Ismaili Society.’ Its membership was based on a number of principles, and would be open only to active researchers of Ismailism and not to the general public. Only those who had at least one published study of Ismailism could be eligible for membership. The proposal was approved and on 6 February 1946 the Ismaili Society was born. Invitations to join were circulated among those eligible and 25 scholars were originally elected as members…. Syrian and Egyptians have been the most industrious members, as for them Ismailism is part of their own history and heritage. But this is not the case in Persia and India. Since Arab and Persian Ismailis suffer from the want of literature on Ismailism, they willingly buy the most worthless booklets from commercial publishers…. During the last 22 years, the [Ismaili] Society has published 28 works in three series…

We also experimented with publishing a non-periodical collection of articles… But it was discontinued because of the shortage of contributors. And still the most important task remains the preparation of critical editions of genuine Ismaili texts. The difficulties are almost insurmountable. Ever since the beginning of this work, I have done everything possible to invite and encourage additional contributors from amongst educated Persians and Arabs. But I have failed completely. .. No one wanted to work for the advancement of knowledge, and even for future monetary gain, but everyone demanded cash, and too much cash, which is not so easy to obtain” (Ibid. p 94-95).

In July 1948, I attended the 21st Congress of Orientalists in Paris, representing the Ismaili Society… In April 1954, I was invited by the Persian government to attend the celebrations of the 900th anniversary of the birth of Avicenna [Ibn Sina], in Tehran and Hamdan. … I also took the opportunity to make some arrangements for my planned work in Alamut and Lamasar where I spent two seasons in 1957 and 1958. This was made possible through a generous grant of £350 contributed by the Khojas of East Africa.”

Fifty Years in the East, The Memoirs of Wladimir Ivanow, Ed. Farhad Daftary, I.B. Tauris, London, 2015

Alamut Ismailis

Remains of fortifications on Alamut rock. Image: Peter Willey, Eagle’s Nest. Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria.

Lamasar was the last of the fortresses to fall to the Mongols. Image: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

(More on Ismaili State of Alamut https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2021/ ... -alamut-2/ [1090-1256])

The revised title page dated Bombay, 1927; the “rough notes” title page is dated Calcutta, India, 1928 and has Wood’s manuscript notations re publication possibilities dated 1934. Image: Annotated catalogue of the Casey A. Wood Collection of Persian, Arabic, and Hindustani manuscripts; Sarah Severson/The Dark Room, McGill Digitized Library

The revised title page is dated: Bombay, 1927; the “rough notes” title page is dated Calcutta, India, 1928 and has Wood’s manuscript notations re publication possibilities dated 1934. Image: Annotated Catalogue of the Casey A. Wood; Sarah Severson/The Dark Room, McGill Digitized Library

A handwritten and a typescript manuscript. Image: Annotated catalogue of the Casey A. Wood Collection of Persian, Arabic, and Hindustani manuscripts; Sarah Severson/The Dark Room, McGill Digitized Library

https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2021/ ... -ismailis/