FAITH AND SCIENCE

Can Humans Directly Observe the Quantum World? Part I

Excerpt:

And yet we might also ask, with a genuine and deep curiosity, why this fundamental framework of human potential is only now being discovered in this advanced and highly prolific age of science? Why has this fundamental knowledge about our very selves and nature – right in front of, inside of, our noses, so to speak – only now emerging, coming to light, also so to speak? Why has this basic nature of our own very capacity to experience the world not been previously evident to us in one way or another, and certainly scientifically?

There are a number of significant and profound answers to these questions, which will be explored in this series. For now we will very briefly point out that in fact there have been people that understood (in their own particular way) that humans are potentially capable of perceiving on such miniscule, hyper-acute, and even microscopic scales. In fact, this knowledge has been held by such people in at least several cultures for centuries, people who practiced engaging these capacities for the very reason that they felt that the realized capacities could lead them to the direct sensory perceptual experience of fundamental properties of the world around them, of the universe. These cultures include the Tibetan, Indian, and East Asian, among others.

Over a decade ago, in Bushell's own research into the sensory-perceptual abilities of highly advanced, long-term, adept practitioners of special forms of observational meditation, he began to realize that some of these practitioners were actually specifically and explicitly attempting to study light with their own highly trained visual capacities, including attempting to perceive the most elementary, fundamental “partless particles” of light. In fact, they were in many ways following the same protocols that contemporary biophysicists and vision scientists employ for testing the human capacity for detecting the least amount of light. The basic protocol includes the following key factors: the need for a completely dark, virtually light-proof chamber, which produces in human vision what is called the dark-adapted scotopic condition; the need for relatively complete motionlessness, as movements can distract and distort perception; the need for extended periods of highly directed and sustained attention; the need for being able to engage in multiple trials of viewing light, i.e., training and learning of the task; the ability to discriminate between actual external sources of light and light spontaneously produced by the body, especially by the visual system itself (internally produced light phenomena known as phosphenes or biophotons).

More...

https://www.scienceandnonduality.com/ar ... a3ac270552

Excerpt:

And yet we might also ask, with a genuine and deep curiosity, why this fundamental framework of human potential is only now being discovered in this advanced and highly prolific age of science? Why has this fundamental knowledge about our very selves and nature – right in front of, inside of, our noses, so to speak – only now emerging, coming to light, also so to speak? Why has this basic nature of our own very capacity to experience the world not been previously evident to us in one way or another, and certainly scientifically?

There are a number of significant and profound answers to these questions, which will be explored in this series. For now we will very briefly point out that in fact there have been people that understood (in their own particular way) that humans are potentially capable of perceiving on such miniscule, hyper-acute, and even microscopic scales. In fact, this knowledge has been held by such people in at least several cultures for centuries, people who practiced engaging these capacities for the very reason that they felt that the realized capacities could lead them to the direct sensory perceptual experience of fundamental properties of the world around them, of the universe. These cultures include the Tibetan, Indian, and East Asian, among others.

Over a decade ago, in Bushell's own research into the sensory-perceptual abilities of highly advanced, long-term, adept practitioners of special forms of observational meditation, he began to realize that some of these practitioners were actually specifically and explicitly attempting to study light with their own highly trained visual capacities, including attempting to perceive the most elementary, fundamental “partless particles” of light. In fact, they were in many ways following the same protocols that contemporary biophysicists and vision scientists employ for testing the human capacity for detecting the least amount of light. The basic protocol includes the following key factors: the need for a completely dark, virtually light-proof chamber, which produces in human vision what is called the dark-adapted scotopic condition; the need for relatively complete motionlessness, as movements can distract and distort perception; the need for extended periods of highly directed and sustained attention; the need for being able to engage in multiple trials of viewing light, i.e., training and learning of the task; the ability to discriminate between actual external sources of light and light spontaneously produced by the body, especially by the visual system itself (internally produced light phenomena known as phosphenes or biophotons).

More...

https://www.scienceandnonduality.com/ar ... a3ac270552

Is Reality Real? How Evolution Blinds us to the Truth About the World

We assume our senses see reality as it is - but that could be just an evolved illusion obscuring the true workings of quantum theory and consciousness

LIFE insurance is a bet on objective reality – a bet that something exists, even if I cease to. This bet seems quite safe to most of us. Life insurance is, accordingly, a lucrative business.

While we are alive and paying premiums, our conscious experiences constitute a different kind of reality, a subjective reality. My experience of a pounding migraine is certainly real to me, but it wouldn’t exist if I didn’t. My visual experience of a red cherry fades to an experience of grey when I shut my eyes. Objective reality, I presume, doesn’t likewise fade to grey.

What is the relationship between the world out there and my internal experience of it – between objective and subjective reality? If I’m sober, and don’t suspect a prank, I’m inclined to believe that when I see a cherry, there is a real cherry whose shape and colour match my experience, and which continues to exist when I look away.

This assumption is central to how we think about ourselves and the world. But is it valid? Experiments my collaborators and I have performed to test the form of sensory perception that evolution has given us suggest a startling conclusion: it isn’t. It leads to a crazy-sounding conclusion, that we may all be gripped by a collective delusion about the nature of the material world. If that is correct, it could have ramifications across the breadth of science—from how consciousness arises to the nature of quantum weirdness to the shape of a future “theory of everything”. Reality may never seem the same again.

The idea that what we perceive might differ from objective reality dates back millennia. Ancient Greek philosopher Plato proposed that we are like prisoners shackled in a fire-lit cave. The action of reality is happening out of sight behind us, and we see only a flickering shadow of it projected onto the cave wall.

Modern science largely abandoned such speculation. For centuries, we have made stunning progress by assuming that physical objects, and the space and time in which they move, are objectively real. This assumption underlies scientific theories from Newtonian mechanics to Albert Einstein’s relativity to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection.

Natural selection, you might think, gives a simple reason why our senses must get it largely right about objective reality. Those of our predecessors who saw more accurately were more successful at performing essential tasks necessary for survival, such as feeding, fighting, fleeing and mating. They were more likely to pass on their genes, which coded for more accurate perceptions. Evolution will naturally select for senses that give us a truer view of the world. As the evolutionary theorist Robert Trivers puts it: “Our sense organs have evolved to give us a marvellously detailed and accurate view of the outside world.”

More....

https://www.scienceandnonduality.com/ar ... -the-world

We assume our senses see reality as it is - but that could be just an evolved illusion obscuring the true workings of quantum theory and consciousness

LIFE insurance is a bet on objective reality – a bet that something exists, even if I cease to. This bet seems quite safe to most of us. Life insurance is, accordingly, a lucrative business.

While we are alive and paying premiums, our conscious experiences constitute a different kind of reality, a subjective reality. My experience of a pounding migraine is certainly real to me, but it wouldn’t exist if I didn’t. My visual experience of a red cherry fades to an experience of grey when I shut my eyes. Objective reality, I presume, doesn’t likewise fade to grey.

What is the relationship between the world out there and my internal experience of it – between objective and subjective reality? If I’m sober, and don’t suspect a prank, I’m inclined to believe that when I see a cherry, there is a real cherry whose shape and colour match my experience, and which continues to exist when I look away.

This assumption is central to how we think about ourselves and the world. But is it valid? Experiments my collaborators and I have performed to test the form of sensory perception that evolution has given us suggest a startling conclusion: it isn’t. It leads to a crazy-sounding conclusion, that we may all be gripped by a collective delusion about the nature of the material world. If that is correct, it could have ramifications across the breadth of science—from how consciousness arises to the nature of quantum weirdness to the shape of a future “theory of everything”. Reality may never seem the same again.

The idea that what we perceive might differ from objective reality dates back millennia. Ancient Greek philosopher Plato proposed that we are like prisoners shackled in a fire-lit cave. The action of reality is happening out of sight behind us, and we see only a flickering shadow of it projected onto the cave wall.

Modern science largely abandoned such speculation. For centuries, we have made stunning progress by assuming that physical objects, and the space and time in which they move, are objectively real. This assumption underlies scientific theories from Newtonian mechanics to Albert Einstein’s relativity to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection.

Natural selection, you might think, gives a simple reason why our senses must get it largely right about objective reality. Those of our predecessors who saw more accurately were more successful at performing essential tasks necessary for survival, such as feeding, fighting, fleeing and mating. They were more likely to pass on their genes, which coded for more accurate perceptions. Evolution will naturally select for senses that give us a truer view of the world. As the evolutionary theorist Robert Trivers puts it: “Our sense organs have evolved to give us a marvellously detailed and accurate view of the outside world.”

More....

https://www.scienceandnonduality.com/ar ... -the-world

-

swamidada_2

- Posts: 297

- Joined: Mon Aug 19, 2019 8:18 pm

JULY 30, 2019

Ulema & science

Jan-e-Alam Khaki July 26, 2019

THE debate about religion and science dates back centuries. The debate is not about a technical matter, but about two realms of knowledge — theological and scientific. There seems to be an epistemological clash of validity between the two, apparently with each claiming sway over human life.

Faith leaders or ulema, in general, boast of having a godly system, which is eternally true, free from error and change. They underplay the hand of man in the understanding, interpretation and application of religious dogmas. Religious leaders are known to oppose scientific developments that they interpret as opposing the key notions of religion due largely to the fear that these would undermine the faith of believers. They may do it with sincerity to religion, and presumably, to save believers from error.

Their tools to deny science are theological and based largely on discursive reason, and not necessarily empirical evidence. They do not always have at their disposal the modern tools of understanding religion, such as scientific history of religions, sociology, psychology, anthropology etc. Reza Aslan’s work God: a Human History is illuminating; it explores how the evolution of religious impulses has taken place in the history of humankind.

Scientists on the other hand, see science as a realm of knowledge strongly reliable, based on human reason and demonstrable empirical evidence. For them, it is a self-corrective and evolving project, modifying itself, and following new evidence through inductive experimentation. It is an approach to generating and judging knowledge.

The debate between religion and science leaves us with no common ground.

A religious mindset on the other hand, sees this changing nature of scientific discoveries as a weakness, boasting of perennial and unchanging ‘truths’. It prefers stability over change; it is dogma-based. In almost all religions, historically opposition to science and scientists has been proverbial, leading to prejudices against, and torture of, scientists, as they are seen as ‘perverted’ souls, hell-bent on defying religious dogmas. This happens often because they use theological criteria to judge science; it is exactly like scientists judging religion or spirituality based on their experimental approach.

The debate between religion and science, put simply, leaves us with no common ground. I, for one argue that the epistemological approaches (forms of knowing and their validity criteria) to both religion and science need to be treated differently as they require different ways of establishing (methodology) and judging (criteria of truth) knowledge and truth claims. We need to be sophisticated enough to see these differences so that we understand each through its own perspective, avoiding one criterion for judging both.

Each branch of science requires different methodologies to study it. Similarly, within religion each branch requires different methodologies of study such as law or spirituality, language or ritual.

Thus, when the ulema judge science using theology, they inevitably make the same mistake as those scientists who judge religion using the scientific method. So, it is necessary that we treat both of them differently, which means we do not downgrade either of them, but acknowledge the unique contribution of each to human welfare.

In my lectures and visits to international audiences, I am always asked by young people the fashionable question: ‘What contribution has religion made to human progress in the last 500 years?’ This is obviously done keeping the magnificent scientific contributions at the back of their mind. I argue, ‘What contributions could one expect from religion to make?’ Did we expect religion to make a technological revolution?

By nature, what science does can be seen and observed; but the transformation brought about by religion in the inner core of people is invisible. However, though exceptional civilisational achievements might have been possible thanks to scientists, it is impossible to ignore the religious ‘faith’ impulse within, and the spiritual inspiration behind for example, civilisational art and architectural marvels, and literary jewels. It is unfair to expect religion to bring, say, a super technological revolution. The major purpose of religion is to not to make technological advances, but to carry out ‘inner engineering’, and transformations, and make people virtuous.

In sum, let us avoid rejecting a scientific approach to solving human problems at the altar of religion; nor should we reject religion because it does not work like science. Let us celebrate both as they address different dimensions of human yearning equally. As the Quran (2:201), says, “...Our Lord! Give us good in this world and good in the Hereafter. ...”. So we seek the best of both religion and science. Let the ulema become a bridge between the two.

The writer is an educationist with an interest in the study of religion and philosophy.

Published in Dawn, July 26th, 2019

/www.dawn.com/news/1496255/ulema-science

Ulema & science

Jan-e-Alam Khaki July 26, 2019

THE debate about religion and science dates back centuries. The debate is not about a technical matter, but about two realms of knowledge — theological and scientific. There seems to be an epistemological clash of validity between the two, apparently with each claiming sway over human life.

Faith leaders or ulema, in general, boast of having a godly system, which is eternally true, free from error and change. They underplay the hand of man in the understanding, interpretation and application of religious dogmas. Religious leaders are known to oppose scientific developments that they interpret as opposing the key notions of religion due largely to the fear that these would undermine the faith of believers. They may do it with sincerity to religion, and presumably, to save believers from error.

Their tools to deny science are theological and based largely on discursive reason, and not necessarily empirical evidence. They do not always have at their disposal the modern tools of understanding religion, such as scientific history of religions, sociology, psychology, anthropology etc. Reza Aslan’s work God: a Human History is illuminating; it explores how the evolution of religious impulses has taken place in the history of humankind.

Scientists on the other hand, see science as a realm of knowledge strongly reliable, based on human reason and demonstrable empirical evidence. For them, it is a self-corrective and evolving project, modifying itself, and following new evidence through inductive experimentation. It is an approach to generating and judging knowledge.

The debate between religion and science leaves us with no common ground.

A religious mindset on the other hand, sees this changing nature of scientific discoveries as a weakness, boasting of perennial and unchanging ‘truths’. It prefers stability over change; it is dogma-based. In almost all religions, historically opposition to science and scientists has been proverbial, leading to prejudices against, and torture of, scientists, as they are seen as ‘perverted’ souls, hell-bent on defying religious dogmas. This happens often because they use theological criteria to judge science; it is exactly like scientists judging religion or spirituality based on their experimental approach.

The debate between religion and science, put simply, leaves us with no common ground. I, for one argue that the epistemological approaches (forms of knowing and their validity criteria) to both religion and science need to be treated differently as they require different ways of establishing (methodology) and judging (criteria of truth) knowledge and truth claims. We need to be sophisticated enough to see these differences so that we understand each through its own perspective, avoiding one criterion for judging both.

Each branch of science requires different methodologies to study it. Similarly, within religion each branch requires different methodologies of study such as law or spirituality, language or ritual.

Thus, when the ulema judge science using theology, they inevitably make the same mistake as those scientists who judge religion using the scientific method. So, it is necessary that we treat both of them differently, which means we do not downgrade either of them, but acknowledge the unique contribution of each to human welfare.

In my lectures and visits to international audiences, I am always asked by young people the fashionable question: ‘What contribution has religion made to human progress in the last 500 years?’ This is obviously done keeping the magnificent scientific contributions at the back of their mind. I argue, ‘What contributions could one expect from religion to make?’ Did we expect religion to make a technological revolution?

By nature, what science does can be seen and observed; but the transformation brought about by religion in the inner core of people is invisible. However, though exceptional civilisational achievements might have been possible thanks to scientists, it is impossible to ignore the religious ‘faith’ impulse within, and the spiritual inspiration behind for example, civilisational art and architectural marvels, and literary jewels. It is unfair to expect religion to bring, say, a super technological revolution. The major purpose of religion is to not to make technological advances, but to carry out ‘inner engineering’, and transformations, and make people virtuous.

In sum, let us avoid rejecting a scientific approach to solving human problems at the altar of religion; nor should we reject religion because it does not work like science. Let us celebrate both as they address different dimensions of human yearning equally. As the Quran (2:201), says, “...Our Lord! Give us good in this world and good in the Hereafter. ...”. So we seek the best of both religion and science. Let the ulema become a bridge between the two.

The writer is an educationist with an interest in the study of religion and philosophy.

Published in Dawn, July 26th, 2019

/www.dawn.com/news/1496255/ulema-science

UBC President speaks at the Ismaili CentreToronto about faith in science

Dr. Santa J. Ono gave a lecture on Faith in the Academy at the Ismaili Centre Toronto on August 6. The President and Vice-Chancellor of the University of British Columbia spoke to the audience about how his faith has been intertwined with his scientific research over the years.

“So much that exists in this world cannot be explained or proven,” said Ono, explaining the realization he had many years ago that was pivotal to the growth of his faith.

According to Ono, Albert Einstein and other scientists have shared this same realization.

Ono shared a quote from Einstein: “‘Everyone who is seriously interested in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that a spirit is manifest in the laws of the universe – a spirit vastly superior to man, and one in the face of which our modest powers must seem humble.’”

Ono’s research is focused on the immune system, eye inflammation, and age related macular degeneration. He has worked at various universities in the United States, including the University of Cincinnati, Emory University, University College London, Johns Hopkins and Harvard before assuming the role of President and Vice-Chancellor of UBC.

During a moderated discussion after Ono’s speech, Dr. Deborah MacLatchy, President and Vice-Chancellor of Wilfrid Laurier University, asked him to elaborate on his early years of university and how faith came to him over time.

Ono equated his life prior to faith to how “a ship will toss over a rough sea.” He explained that faith provided him with “an anchor.”

Once he began his university training at age 17, Ono began to feel something missing in his life. He encountered new friends who told him about their religion, and when he entered their place of worship - their Church - he felt moved.

Ono discussed how once he embraced religion, he had to make conscious decisions about how vocal to be about his faith. He recalled one colleague cautioning him to be careful, telling him others would look at a faculty member who openly observes faith as lacking a rigorous scientific mind.

The UBC President ultimately came to the conclusion that he would be forthright and use his faith to create dialogue.

Through studying science for several decades, Ono said he has become more humble.

“Many things we believe to be true at a given time - 5, 10, 15 years later turn out not to be true,” he said, explaining that faith has made him a better scientist because it has made him more aware of the limitations of being human. Now, after decades of struggling with the notion of science and faith, Ono does not feel any tension between the two.

At UBC, Ono aspires to create an intentionally diverse environment that reflects the communities which it serves. He talked about how UBC is one of the most international universities in the world, and how its diversity creates an enriched environment for teaching, research, and learning as well as bringing together people from different faiths.

Ono expressed that a diverse environment brings differing views and perspectives, which in some cases causes uncomfortable situations. There is a blurred line between freedom of speech and hate speech, he said, but in his experience, bringing together differing opinions rather than censoring them is usually the right approach.

He also discussed his views on leadership.

“A leader has to start from a position of humility and respect others, everyone,” Ono said, explaining the concept of servant leadership. He explained a leader must be careful about the risks of intellectual arrogance: if one is not open to the idea of being wrong or to different perspectives, it can limit experiments and research.

Nida Hashimi, a university student entering her fourth year, asked about the need to build humility into students before they enter the workplace. Ono answered that as society has become so fast-paced and people have become more focused on the end result, the need for inter-generational education and mentorship has increased.

Ono said he sees this humility and intergenerational mentorship in the Ismaili community and he hopes to see more of it everywhere.

https://the.ismaili/centres/ubc-preside ... rce=Direct

Dr. Santa J. Ono gave a lecture on Faith in the Academy at the Ismaili Centre Toronto on August 6. The President and Vice-Chancellor of the University of British Columbia spoke to the audience about how his faith has been intertwined with his scientific research over the years.

“So much that exists in this world cannot be explained or proven,” said Ono, explaining the realization he had many years ago that was pivotal to the growth of his faith.

According to Ono, Albert Einstein and other scientists have shared this same realization.

Ono shared a quote from Einstein: “‘Everyone who is seriously interested in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that a spirit is manifest in the laws of the universe – a spirit vastly superior to man, and one in the face of which our modest powers must seem humble.’”

Ono’s research is focused on the immune system, eye inflammation, and age related macular degeneration. He has worked at various universities in the United States, including the University of Cincinnati, Emory University, University College London, Johns Hopkins and Harvard before assuming the role of President and Vice-Chancellor of UBC.

During a moderated discussion after Ono’s speech, Dr. Deborah MacLatchy, President and Vice-Chancellor of Wilfrid Laurier University, asked him to elaborate on his early years of university and how faith came to him over time.

Ono equated his life prior to faith to how “a ship will toss over a rough sea.” He explained that faith provided him with “an anchor.”

Once he began his university training at age 17, Ono began to feel something missing in his life. He encountered new friends who told him about their religion, and when he entered their place of worship - their Church - he felt moved.

Ono discussed how once he embraced religion, he had to make conscious decisions about how vocal to be about his faith. He recalled one colleague cautioning him to be careful, telling him others would look at a faculty member who openly observes faith as lacking a rigorous scientific mind.

The UBC President ultimately came to the conclusion that he would be forthright and use his faith to create dialogue.

Through studying science for several decades, Ono said he has become more humble.

“Many things we believe to be true at a given time - 5, 10, 15 years later turn out not to be true,” he said, explaining that faith has made him a better scientist because it has made him more aware of the limitations of being human. Now, after decades of struggling with the notion of science and faith, Ono does not feel any tension between the two.

At UBC, Ono aspires to create an intentionally diverse environment that reflects the communities which it serves. He talked about how UBC is one of the most international universities in the world, and how its diversity creates an enriched environment for teaching, research, and learning as well as bringing together people from different faiths.

Ono expressed that a diverse environment brings differing views and perspectives, which in some cases causes uncomfortable situations. There is a blurred line between freedom of speech and hate speech, he said, but in his experience, bringing together differing opinions rather than censoring them is usually the right approach.

He also discussed his views on leadership.

“A leader has to start from a position of humility and respect others, everyone,” Ono said, explaining the concept of servant leadership. He explained a leader must be careful about the risks of intellectual arrogance: if one is not open to the idea of being wrong or to different perspectives, it can limit experiments and research.

Nida Hashimi, a university student entering her fourth year, asked about the need to build humility into students before they enter the workplace. Ono answered that as society has become so fast-paced and people have become more focused on the end result, the need for inter-generational education and mentorship has increased.

Ono said he sees this humility and intergenerational mentorship in the Ismaili community and he hopes to see more of it everywhere.

https://the.ismaili/centres/ubc-preside ... rce=Direct

Mind the Gap Between Science and Religion

Have you heard that we may be living in a computer simulation? Or that our universe is only one of infinitely many parallel worlds in which you live every possible variation of your life? Or that the laws of nature derive from a beautiful, higher-dimensional theory that is super-symmetric and explains, supposedly, everything?

I’ve heard that too. It’s how my research area, fundamental physics, often ends up making headlines: With insights about the nature of reality so mind-boggling you can’t believe it’s still science. Unfortunately, in many cases it’s indeed not science.

Take the idea that we live in a computer simulation. According to our best current knowledge, the universe follows rules that are encoded by a set of equations. We don’t know these equations completely (yet!), but you could rightfully say the universe computes in real time whatever are the correct equations. In that sense, we trivially “live in a computer,” but that’s just a funny way to talk about the laws of nature.

You may more specifically ask whether our universe’s computation is similar to the computation performed by computers we build ourselves, that is, pushing around units of information in discrete time-steps. This is a testable hypothesis, and to the extent that it has been tested, it has been falsified. It is not easy to obtain the already known laws of nature using discrete, local operations even approximately, and this mathematical difficulty has, so far, rendered scientifically well-posed versions of the simulation hypotheses incompatible with evidence.

And finally, if you are really asking whether our universe has been programmed by a superior intelligence, that’s just a badly concealed form of religion. Since this hypothesis is untestable inside the supposed simulation, it’s not scientific. This is not to say it is in conflict with science. You can believe it, if you want to. But believing in an omnipotent Programmer is not science—it’s tech-bro monotheism. And without that Programmer, the simulation hypothesis is just a modern-day version of the 18th century clockwork universe, a sign of our limited imagination more than anything else.

t’s a similar story with all those copies of yourself in parallel worlds. You can believe that they exist, all right. This belief is not in conflict with science and it is surely an entertaining speculation. But there is no way you can ever test whether your copies exist, therefore their existence is not a scientific hypothesis.

Most worryingly, this confusion of religion and science does not come from science journalists; it comes directly from the practitioners in my field. Many of my colleagues have become careless in separating belief from fact. They speak of existence without stopping to ask what it means for something to exist in the first place. They confuse postulates with conclusions and mathematics with reality. They don’t know what it means to explain something in scientific terms, and they no longer shy away from hypotheses that are untestable even in principle.

Particularly damaging to fundamental physics has been the belief that the equations which describe nature must be beautiful by human standards. There is no rational reason why this should be so, but faith in beautiful math has become pervasive in the community. And that’s despite the fact that relying on beauty as a guide to new natural laws has historically worked badly: The mechanical clockwork universe was once considered beautiful. So were circular planetary orbits, and an eternally unchanging universe. All of which, it turns out, is wrong.

And relying on beauty is still working badly for physicists. We see the tragedy playing out in the ongoing failure of ideas like a unification of the fundamental forces, a theory of everything, or new types of symmetries that experiments continue to not find. Such pretty hypotheses remain popular among physicists even though they haven’t led anywhere for decades. The recent Special Breakthrough Prize for Fundamental Physics drove home the point. The prize was awarded for Supergravity, a theory, invented in the 1970s, that is widely praised for its elegance and beauty. Supergravity has to date no observational support. It wins prizes nevertheless.

This blurring of the line between science and religion is not innocuous. Resources—both financial and human—that go into elucidating details of untestable ideas are not available for research that could lead to much-needed progress. I like the idea that the laws of nature are beautiful and the universe was made for a purpose as much as everybody else, and I appreciate public interest in our research anytime. But let’s not call it science when it is really not.

We have fought hard for secularism, and we don’t want religious leaders to meddle in scientific debate. Scientists, likewise, should respect the limits of their discipline.

Sabine Hossenfelder is a Research Fellow at the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies where she works on physics beyond the standard model, phenomenological quantum gravity, and modifications of general relativity. If you want to know more about what is going wrong with the foundations of physics, read her book Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray.

http://nautil.us//blog/mind-the-gap-bet ... d-religion

Have you heard that we may be living in a computer simulation? Or that our universe is only one of infinitely many parallel worlds in which you live every possible variation of your life? Or that the laws of nature derive from a beautiful, higher-dimensional theory that is super-symmetric and explains, supposedly, everything?

I’ve heard that too. It’s how my research area, fundamental physics, often ends up making headlines: With insights about the nature of reality so mind-boggling you can’t believe it’s still science. Unfortunately, in many cases it’s indeed not science.

Take the idea that we live in a computer simulation. According to our best current knowledge, the universe follows rules that are encoded by a set of equations. We don’t know these equations completely (yet!), but you could rightfully say the universe computes in real time whatever are the correct equations. In that sense, we trivially “live in a computer,” but that’s just a funny way to talk about the laws of nature.

You may more specifically ask whether our universe’s computation is similar to the computation performed by computers we build ourselves, that is, pushing around units of information in discrete time-steps. This is a testable hypothesis, and to the extent that it has been tested, it has been falsified. It is not easy to obtain the already known laws of nature using discrete, local operations even approximately, and this mathematical difficulty has, so far, rendered scientifically well-posed versions of the simulation hypotheses incompatible with evidence.

And finally, if you are really asking whether our universe has been programmed by a superior intelligence, that’s just a badly concealed form of religion. Since this hypothesis is untestable inside the supposed simulation, it’s not scientific. This is not to say it is in conflict with science. You can believe it, if you want to. But believing in an omnipotent Programmer is not science—it’s tech-bro monotheism. And without that Programmer, the simulation hypothesis is just a modern-day version of the 18th century clockwork universe, a sign of our limited imagination more than anything else.

t’s a similar story with all those copies of yourself in parallel worlds. You can believe that they exist, all right. This belief is not in conflict with science and it is surely an entertaining speculation. But there is no way you can ever test whether your copies exist, therefore their existence is not a scientific hypothesis.

Most worryingly, this confusion of religion and science does not come from science journalists; it comes directly from the practitioners in my field. Many of my colleagues have become careless in separating belief from fact. They speak of existence without stopping to ask what it means for something to exist in the first place. They confuse postulates with conclusions and mathematics with reality. They don’t know what it means to explain something in scientific terms, and they no longer shy away from hypotheses that are untestable even in principle.

Particularly damaging to fundamental physics has been the belief that the equations which describe nature must be beautiful by human standards. There is no rational reason why this should be so, but faith in beautiful math has become pervasive in the community. And that’s despite the fact that relying on beauty as a guide to new natural laws has historically worked badly: The mechanical clockwork universe was once considered beautiful. So were circular planetary orbits, and an eternally unchanging universe. All of which, it turns out, is wrong.

And relying on beauty is still working badly for physicists. We see the tragedy playing out in the ongoing failure of ideas like a unification of the fundamental forces, a theory of everything, or new types of symmetries that experiments continue to not find. Such pretty hypotheses remain popular among physicists even though they haven’t led anywhere for decades. The recent Special Breakthrough Prize for Fundamental Physics drove home the point. The prize was awarded for Supergravity, a theory, invented in the 1970s, that is widely praised for its elegance and beauty. Supergravity has to date no observational support. It wins prizes nevertheless.

This blurring of the line between science and religion is not innocuous. Resources—both financial and human—that go into elucidating details of untestable ideas are not available for research that could lead to much-needed progress. I like the idea that the laws of nature are beautiful and the universe was made for a purpose as much as everybody else, and I appreciate public interest in our research anytime. But let’s not call it science when it is really not.

We have fought hard for secularism, and we don’t want religious leaders to meddle in scientific debate. Scientists, likewise, should respect the limits of their discipline.

Sabine Hossenfelder is a Research Fellow at the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies where she works on physics beyond the standard model, phenomenological quantum gravity, and modifications of general relativity. If you want to know more about what is going wrong with the foundations of physics, read her book Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray.

http://nautil.us//blog/mind-the-gap-bet ... d-religion

BOOK

On the Mystery of Being: Contemporary Insights on the Convergence of Science and Spirituality

Who are we? What is our place in this vast and ever-evolving universe? Where do science and spirituality meet?

If you’ve pondered these questions, you’re not alone. Join some of the most spiritually curious and renowned minds of our time for an exploration into the mystery of being. From founders of the Science and Nonduality (SAND) conference, Maurizio and Zaya Benazzo, On the Mystery of Being brings together an array of visionary spiritual leaders, psychologists, philosophers, scientists, teachers, authors, and healers to celebrate and explore what it means to be human.

This beautifully arranged collection of essays and insights highlight topics on the convergence of spirituality and science, weaving scientific theory and spiritual wisdom from some of the most influential thinkers of our time—including Deepak Chopra, Rupert Spira, Adyashanti, and many more—with pieces that get straight to the heart of the matter.

As a powerful antidote to our chaotic and materialist modern world, this dazzling volume offers timeless wisdom and new insight into humanity’s age-old questions. On the Mystery of Being also reveals the cutting-edge explorations at the intersection of science and spirituality today. May it encourage your spirit, challenge your mind, and deepen your understanding of our interconnectedness.

https://www.amazon.com/Mystery-Being-Co ... B07MT9443D

On the Mystery of Being: Contemporary Insights on the Convergence of Science and Spirituality

Who are we? What is our place in this vast and ever-evolving universe? Where do science and spirituality meet?

If you’ve pondered these questions, you’re not alone. Join some of the most spiritually curious and renowned minds of our time for an exploration into the mystery of being. From founders of the Science and Nonduality (SAND) conference, Maurizio and Zaya Benazzo, On the Mystery of Being brings together an array of visionary spiritual leaders, psychologists, philosophers, scientists, teachers, authors, and healers to celebrate and explore what it means to be human.

This beautifully arranged collection of essays and insights highlight topics on the convergence of spirituality and science, weaving scientific theory and spiritual wisdom from some of the most influential thinkers of our time—including Deepak Chopra, Rupert Spira, Adyashanti, and many more—with pieces that get straight to the heart of the matter.

As a powerful antidote to our chaotic and materialist modern world, this dazzling volume offers timeless wisdom and new insight into humanity’s age-old questions. On the Mystery of Being also reveals the cutting-edge explorations at the intersection of science and spirituality today. May it encourage your spirit, challenge your mind, and deepen your understanding of our interconnectedness.

https://www.amazon.com/Mystery-Being-Co ... B07MT9443D

HISTORY OF IDEAS - Religion

Video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ge071m9 ... HuKRw9C_6J

Religion was an ingenious solution to many of mankind's earliest fears and needs. Religion is now implausible to many, but the needs remain. That is the challenge of our times

Video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ge071m9 ... HuKRw9C_6J

Religion was an ingenious solution to many of mankind's earliest fears and needs. Religion is now implausible to many, but the needs remain. That is the challenge of our times

Is there a Science of Self-Actualization?

Hi Karim,

Are you familiar with the work of Ken Wilber?

Although

he doesn’t spend much time in the limelight, Ken is probably one of the 2 or 3 most influential spiritual leaders alive today.

His decades of work mapping

the science of human transformation has had a profound impact on my own thinking and is probably one of the most important contributions to spirituality in our time.

Ken has been called “The Einstein of Consciousness” and been hailed by world leaders, changemakers and visionaries.

My good friend Marianne Williamson calls Ken “The teacher of teachers.” She asks, “Who among us can be serious about the work of transformation without understanding his remarkable work?”

Tony Robbins says, “Ken Wilber is a genius. I don’t think there is anybody alive who has developed a more comprehensive theory of life, psychology and spirituality."

Although Ken's work has had a profound influence on most of today's luminaries, you won't find him speaking on the conference circuit or in the media.

It is therefore with great pleasure that I’m writing today to let you know about a rare opportunity to learn directly from Ken in a 7-Part online training he’s offering starting this week at no charge.

His new course is called “The Science of Self-Actualization: The 5 Essential Truths of Your Full Potential” and you can enroll at no cost until November 22nd.

In this inspiring new online training, Ken shows us what the latest research into human development reveals about how we can cultivate and ultimately actualize the highest reaches of our potentials.

If you’re interested in unlocking the full scope of your highest human possibilities, I strongly encourage you to reserve your space here: The Science of Self-Actualization with Ken Wilber. https://signup.self-actualize.com/?opri ... ref=192826

One essential difference between Ken’s work and that of many other teachers is that while most show their students a particular path, Ken’s shows you a complete map—a comprehensive map that embraces and includes all paths, Eastern and Western, ancient and modern.

You may have heard the metaphor that there are many paths up the mountain, yet they all take you to the same summit.

In some way, nearly all teachers act as a guide, helping seekers to navigate the slippery slopes of these mountain paths to reach the elusive summit of our highest potential.

Ken, on the other hand, is a cartographer of this mountain, a master map-maker of our psychological and spiritual evolution.

His work illuminates the complete map of our inner terrain, while also skillfully guiding us past the pitfalls, to the most effective paths for us to reach the summit of our highest self.

This is why he is in a league of his own. And it’s why I agree with Marianne that Ken Wilber’s wisdom is vital for any seeker who wants to ascend to their highest potential.

While I do love and support a great many luminaries, there is no one that I am more proud to recommend than Ken.

If you’ve never had a chance to listen to Ken’s extraordinary teachings, I encourage you to learn more about his upcoming complimentary online 7-part training at the link below:

The Science of Self Actualization with Ken Wilber

https://signup.self-actualize.com/?opri ... ref=192826

This work may very well change your life, so I hope you can join him online for this powerful new course offered at no charge.

To your highest potentials,

Craig Hamilton

Founder, Integral Enlightenment

Hi Karim,

Are you familiar with the work of Ken Wilber?

Although

he doesn’t spend much time in the limelight, Ken is probably one of the 2 or 3 most influential spiritual leaders alive today.

His decades of work mapping

the science of human transformation has had a profound impact on my own thinking and is probably one of the most important contributions to spirituality in our time.

Ken has been called “The Einstein of Consciousness” and been hailed by world leaders, changemakers and visionaries.

My good friend Marianne Williamson calls Ken “The teacher of teachers.” She asks, “Who among us can be serious about the work of transformation without understanding his remarkable work?”

Tony Robbins says, “Ken Wilber is a genius. I don’t think there is anybody alive who has developed a more comprehensive theory of life, psychology and spirituality."

Although Ken's work has had a profound influence on most of today's luminaries, you won't find him speaking on the conference circuit or in the media.

It is therefore with great pleasure that I’m writing today to let you know about a rare opportunity to learn directly from Ken in a 7-Part online training he’s offering starting this week at no charge.

His new course is called “The Science of Self-Actualization: The 5 Essential Truths of Your Full Potential” and you can enroll at no cost until November 22nd.

In this inspiring new online training, Ken shows us what the latest research into human development reveals about how we can cultivate and ultimately actualize the highest reaches of our potentials.

If you’re interested in unlocking the full scope of your highest human possibilities, I strongly encourage you to reserve your space here: The Science of Self-Actualization with Ken Wilber. https://signup.self-actualize.com/?opri ... ref=192826

One essential difference between Ken’s work and that of many other teachers is that while most show their students a particular path, Ken’s shows you a complete map—a comprehensive map that embraces and includes all paths, Eastern and Western, ancient and modern.

You may have heard the metaphor that there are many paths up the mountain, yet they all take you to the same summit.

In some way, nearly all teachers act as a guide, helping seekers to navigate the slippery slopes of these mountain paths to reach the elusive summit of our highest potential.

Ken, on the other hand, is a cartographer of this mountain, a master map-maker of our psychological and spiritual evolution.

His work illuminates the complete map of our inner terrain, while also skillfully guiding us past the pitfalls, to the most effective paths for us to reach the summit of our highest self.

This is why he is in a league of his own. And it’s why I agree with Marianne that Ken Wilber’s wisdom is vital for any seeker who wants to ascend to their highest potential.

While I do love and support a great many luminaries, there is no one that I am more proud to recommend than Ken.

If you’ve never had a chance to listen to Ken’s extraordinary teachings, I encourage you to learn more about his upcoming complimentary online 7-part training at the link below:

The Science of Self Actualization with Ken Wilber

https://signup.self-actualize.com/?opri ... ref=192826

This work may very well change your life, so I hope you can join him online for this powerful new course offered at no charge.

To your highest potentials,

Craig Hamilton

Founder, Integral Enlightenment

Mawlana Hazar Imam: “I am struck by the close relationship which exists between intellect and the faith”

Posted by Nimira Dewji

“In Islamic belief, knowledge is two-fold. There is that revealed through the Holy Prophet [Salla-llahu ‘alayhi wa- sallam] and that which man discovers by virtue of his own intellect. Nor do these two involve any contradiction, provided man remembers that his own mind is itself the creation of God. Without this humility, no balance is possible. With it, there are no barriers.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam, Karachi, Pakistan, March 16, 1983

Speech

******

“The divine Intellect, ‘Aql-Qul,’ both transcends and informs the human intellect. It is this intellect which enables man to strive towards two aims dictated by the Faith: that he should reflect upon the environment Allah has given him and that he should know himself. It is the light of intellect which distinguishes the complete human being from the human animal and developing that intellect requires free inquiry. The man of Faith who fails to pursue intellectual search is likely to have only a limited comprehension of Allah’s creation. Indeed, it is man’s intellect that enables him to expand his vision of that creation…

If the frontiers of physics are changing, it is due to scientists discovering more and more about the universe, even though they will never be able to probe its totality, since Allah’s creation is limitless and continuous…

The Holy Qur’an’s encouragement to study nature and the physical world around us gave the original impetus to scientific inquiry among Muslims. Exchanges of knowledge between institutions and nations and the widening of man’s intellectual horizons are essentially Islamic concepts. The Faith urges freedom of intellectual enquiry and this freedom does not mean that knowledge will lose its spiritual dimension. That dimension is indeed itself a field for intellectual enquiry.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam, Karachi, Pakistan, November 11, 1985

Speech

*******

Hazar Imam Aga Khan Central Asia

Source: The Ismaili, May 1995

“…I am struck by the close relationship which exists between intellect and the faith. During the glorious periods of Muslim history, Muslim thinkers, scientists and philosophers were beacons of light, sharing their knowledge freely with the non-Muslim world, indeed often leading it.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam, Bishkek, Kyrgyz Republic, May 30, 1995

Speech published in The Ismaili, May 1995

******

“Education has been important to my family for a long time. My forefathers founded Al Azhar University in Cairo some 1,000 years ago, at the time of the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt. Discovery of knowledge was seen by those founders as an embodiment of religious faith, and faith as reinforced by knowledge of workings of the Creator’s physical world. The form of universities has changed over those 1,000 years, but that reciprocity between faith and knowledge remains a source of strength.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam, Cambridge, USA May 27, 1994

Speech

https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/ ... rce=Direct

Posted by Nimira Dewji

“In Islamic belief, knowledge is two-fold. There is that revealed through the Holy Prophet [Salla-llahu ‘alayhi wa- sallam] and that which man discovers by virtue of his own intellect. Nor do these two involve any contradiction, provided man remembers that his own mind is itself the creation of God. Without this humility, no balance is possible. With it, there are no barriers.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam, Karachi, Pakistan, March 16, 1983

Speech

******

“The divine Intellect, ‘Aql-Qul,’ both transcends and informs the human intellect. It is this intellect which enables man to strive towards two aims dictated by the Faith: that he should reflect upon the environment Allah has given him and that he should know himself. It is the light of intellect which distinguishes the complete human being from the human animal and developing that intellect requires free inquiry. The man of Faith who fails to pursue intellectual search is likely to have only a limited comprehension of Allah’s creation. Indeed, it is man’s intellect that enables him to expand his vision of that creation…

If the frontiers of physics are changing, it is due to scientists discovering more and more about the universe, even though they will never be able to probe its totality, since Allah’s creation is limitless and continuous…

The Holy Qur’an’s encouragement to study nature and the physical world around us gave the original impetus to scientific inquiry among Muslims. Exchanges of knowledge between institutions and nations and the widening of man’s intellectual horizons are essentially Islamic concepts. The Faith urges freedom of intellectual enquiry and this freedom does not mean that knowledge will lose its spiritual dimension. That dimension is indeed itself a field for intellectual enquiry.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam, Karachi, Pakistan, November 11, 1985

Speech

*******

Hazar Imam Aga Khan Central Asia

Source: The Ismaili, May 1995

“…I am struck by the close relationship which exists between intellect and the faith. During the glorious periods of Muslim history, Muslim thinkers, scientists and philosophers were beacons of light, sharing their knowledge freely with the non-Muslim world, indeed often leading it.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam, Bishkek, Kyrgyz Republic, May 30, 1995

Speech published in The Ismaili, May 1995

******

“Education has been important to my family for a long time. My forefathers founded Al Azhar University in Cairo some 1,000 years ago, at the time of the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt. Discovery of knowledge was seen by those founders as an embodiment of religious faith, and faith as reinforced by knowledge of workings of the Creator’s physical world. The form of universities has changed over those 1,000 years, but that reciprocity between faith and knowledge remains a source of strength.”

Mawlana Hazar Imam, Cambridge, USA May 27, 1994

Speech

https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2019/ ... rce=Direct

Where Is My Mind?

The rise and fall of the claustrum epitomizes the hunt for consciousness in the brain.

In 1976, Francis Crick arrived at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, overlooking a Pacific Shangri-La with cotton candy skies and a beaming, blue-green sea. He had already won the Nobel Prize for co-discovering the double-helix structure of DNA, revealing the basis of life to be a purely physical, not a mystical, process. He hoped to do the same thing for consciousness. If matter was strange enough to explain a creature’s life code, he thought, maybe it’s strange enough to explain a creature’s mind, too.

For something that everybody walks around with everyday, consciousness wouldn’t seem to be as immense a puzzle as the origin of the universe. It’s just that difficult to imagine how subjective experience can arise from basic physical elements like atoms and molecules. It seems like there must be more to the story. Small wonder, then, that for ages people believed that consciousness was a function of the soul, far beyond the grasp of science. Consequently, consciousness became the strongest argument for vitalism, the idea that life is dependent on immaterial or non-physical forces. Crick, a lifelong defender of materialism, was absolutely determined when he arrived in California to dispel the notion from consciousness and blaze a path toward solving it.

In the last 30 years of his life, he propelled a revolution in neuroscience by molecular biology, challenging the brightest minds in the field, usually over tea, and publishing works on his “astonishing hypothesis” that consciousness arises from the brain alone. On his deathbed in 2005, Crick, together with his friend and colleague Christof Koch, published a final article, “What is the function of the claustrum?”, which reignited the search for the physical location of consciousness in the brain.1 It proposed the claustrum, a set of neurons coincidentally shaped like a hammock, as the seat of consciousness because it receives “input from almost all regions of cortex, and projects back to almost all regions of cortex,” the wrinkled surface of the brain responsible for conscious features ranging from sensation to personality. The promising idea would go on to spur probing studies on the nature of consciousness, and the beguiling role of the claustrum, that continue today.

More....

http://nautil.us/issue/79/catalysts/whe ... b00bf1f6eb

The rise and fall of the claustrum epitomizes the hunt for consciousness in the brain.

In 1976, Francis Crick arrived at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California, overlooking a Pacific Shangri-La with cotton candy skies and a beaming, blue-green sea. He had already won the Nobel Prize for co-discovering the double-helix structure of DNA, revealing the basis of life to be a purely physical, not a mystical, process. He hoped to do the same thing for consciousness. If matter was strange enough to explain a creature’s life code, he thought, maybe it’s strange enough to explain a creature’s mind, too.

For something that everybody walks around with everyday, consciousness wouldn’t seem to be as immense a puzzle as the origin of the universe. It’s just that difficult to imagine how subjective experience can arise from basic physical elements like atoms and molecules. It seems like there must be more to the story. Small wonder, then, that for ages people believed that consciousness was a function of the soul, far beyond the grasp of science. Consequently, consciousness became the strongest argument for vitalism, the idea that life is dependent on immaterial or non-physical forces. Crick, a lifelong defender of materialism, was absolutely determined when he arrived in California to dispel the notion from consciousness and blaze a path toward solving it.

In the last 30 years of his life, he propelled a revolution in neuroscience by molecular biology, challenging the brightest minds in the field, usually over tea, and publishing works on his “astonishing hypothesis” that consciousness arises from the brain alone. On his deathbed in 2005, Crick, together with his friend and colleague Christof Koch, published a final article, “What is the function of the claustrum?”, which reignited the search for the physical location of consciousness in the brain.1 It proposed the claustrum, a set of neurons coincidentally shaped like a hammock, as the seat of consciousness because it receives “input from almost all regions of cortex, and projects back to almost all regions of cortex,” the wrinkled surface of the brain responsible for conscious features ranging from sensation to personality. The promising idea would go on to spur probing studies on the nature of consciousness, and the beguiling role of the claustrum, that continue today.

More....

http://nautil.us/issue/79/catalysts/whe ... b00bf1f6eb

Huston Smith, "Why Religion Matters: The Future of Faith"

Video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=obeI1ea ... rce=Direct

Kenan Institute for Ethics - Speeches & Panels - Video - Why Religion Matters: The Future of Faith in an Age on Disbelief -

2000-10-26, Huston Smith lecture on "Why Religion Matters: The Future of Faith in an Age on Disbelief." Huston Smith is the Thomas J. Watson Professor of Religion and Distinguished Adjunct Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus, Syracuse University

Video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=obeI1ea ... rce=Direct

Kenan Institute for Ethics - Speeches & Panels - Video - Why Religion Matters: The Future of Faith in an Age on Disbelief -

2000-10-26, Huston Smith lecture on "Why Religion Matters: The Future of Faith in an Age on Disbelief." Huston Smith is the Thomas J. Watson Professor of Religion and Distinguished Adjunct Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus, Syracuse University

The Joy of Cosmic Mediocrity

It’s lonely to be an exceptional planet.

One of the greatest debates in the long history of astronomy has been that of exceptionalism versus mediocrity—and one of the great satisfactions of modern times has been watching the arguments for mediocrity emerge triumphant. Far more than just a high-minded clash of abstract ideas, this debate has shaped the way we humans evaluate our place in the universe. It has defined, in important ways, how we measure the very value of our existence.

In the scientific context, exceptional means something very different than it does in the everyday language of, say, football commentary or restaurant reviews. To be exceptional is to be unique and solitary. To be mediocre is to be one of many, to be a part of a community. If Earth is exceptional, then we might be profoundly alone. There might not be any other intelligent beings like ourselves in the universe. Perhaps no other habitable planets like ours. Perhaps no other planets at all, beyond the neighboring worlds of our own solar system.

Powell_BREAKER-3

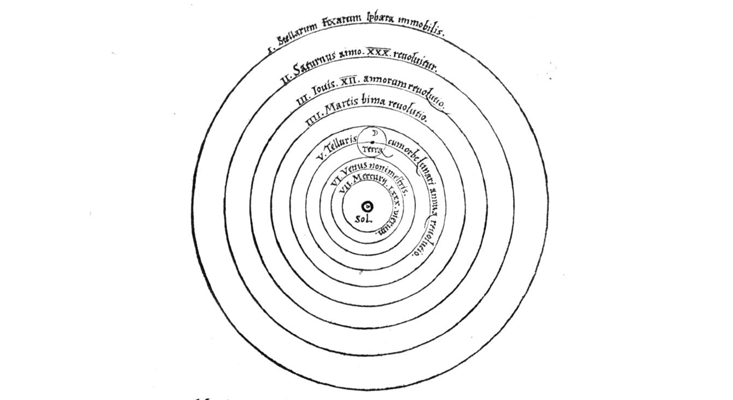

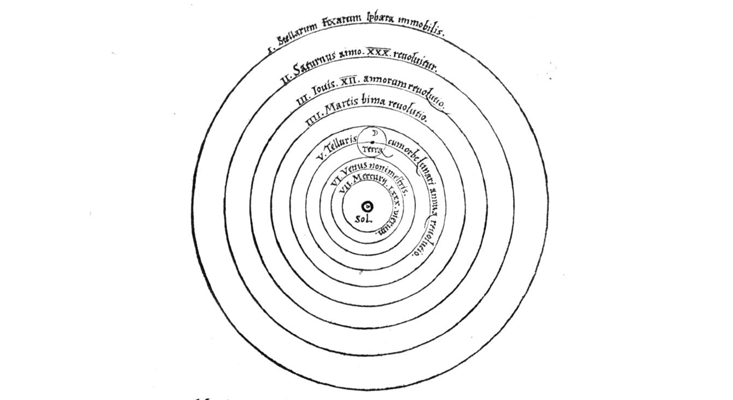

MEDIOCRITY #3: In the heliocentric system of Nicolaus Copernicus, Earth is just third in a set of planets circling the sun. But there is comfort in being part of a family.Mikołaj Kopernik

If Earth is mediocre, the logic runs the other way. We might live in a galaxy teeming with planets, many of them potentially habitable, some of them actually harboring life. In the mediocre case, we bipedal little humans might not be the only sentient creatures peering out into the depths of space, wondering if anyone else is peering back.

Today, the broadest version of exceptionalism has been thoroughly disproven, as astronomers have discovered 4,150 confirmed exoplanets, a tally that increases almost daily. The roster of alien worlds includes a remarkable variety of forms, many of which have no equivalent in our solar system. And that is just a limited sampling from the stars in our local corner of the galaxy.

We do not yet have the technology needed to find a close analog of Earth orbiting a close analog of the sun, so we still know little about how common or rare such worlds may be. The question of alien life is still wide open. What we do know is that the Milky Way is home to a tremendous number of other planets. In that sense, at least, we are certainly not exceptional, and Earth is certainly not alone.

More...

http://nautil.us/issue/79/catalysts/the ... b00bf1f6eb

It’s lonely to be an exceptional planet.

One of the greatest debates in the long history of astronomy has been that of exceptionalism versus mediocrity—and one of the great satisfactions of modern times has been watching the arguments for mediocrity emerge triumphant. Far more than just a high-minded clash of abstract ideas, this debate has shaped the way we humans evaluate our place in the universe. It has defined, in important ways, how we measure the very value of our existence.

In the scientific context, exceptional means something very different than it does in the everyday language of, say, football commentary or restaurant reviews. To be exceptional is to be unique and solitary. To be mediocre is to be one of many, to be a part of a community. If Earth is exceptional, then we might be profoundly alone. There might not be any other intelligent beings like ourselves in the universe. Perhaps no other habitable planets like ours. Perhaps no other planets at all, beyond the neighboring worlds of our own solar system.

Powell_BREAKER-3

MEDIOCRITY #3: In the heliocentric system of Nicolaus Copernicus, Earth is just third in a set of planets circling the sun. But there is comfort in being part of a family.Mikołaj Kopernik

If Earth is mediocre, the logic runs the other way. We might live in a galaxy teeming with planets, many of them potentially habitable, some of them actually harboring life. In the mediocre case, we bipedal little humans might not be the only sentient creatures peering out into the depths of space, wondering if anyone else is peering back.

Today, the broadest version of exceptionalism has been thoroughly disproven, as astronomers have discovered 4,150 confirmed exoplanets, a tally that increases almost daily. The roster of alien worlds includes a remarkable variety of forms, many of which have no equivalent in our solar system. And that is just a limited sampling from the stars in our local corner of the galaxy.

We do not yet have the technology needed to find a close analog of Earth orbiting a close analog of the sun, so we still know little about how common or rare such worlds may be. The question of alien life is still wide open. What we do know is that the Milky Way is home to a tremendous number of other planets. In that sense, at least, we are certainly not exceptional, and Earth is certainly not alone.

More...

http://nautil.us/issue/79/catalysts/the ... b00bf1f6eb

Why the "Universe from Nothing" is a Non-Starter

I was relaxing one evening when the quietness of the house was destroyed by the sound of a thunderous crash upstairs. Leaping to my feet, I yelled, “What was THAT?”

“Nothing!” was the reply that floated down the stairwell from a person not yet old enough to realize that there are few adults indeed who find such an explanation satisfying.

Strangely, using “nothing” as an explanation has recently been suggested for something much more impressive than a thundering roar on the second floor. I refer to the origin of the entire universe—the biggest crash of all, as it were.

During the course of the 20th century, scientists discovered something that poses a serious philosophical problem for atheism. Cosmologists observed that the entire universe is expanding. The consensus, working backward in time, is that it had a beginning which, of course, raises the question, “What caused THAT?”

Strangely, using “nothing” as an explanation has recently been suggested for something much more impressive than a thundering roar on the second floor.

There appears to be no escape from the reality of a beginning for physical reality, both scientifically (1) as well as mathematically. (2) Although Steven Hawking died an atheist (so far as I am aware), he had the insight to state, “A point of creation would be a place where science broke down. One would have to appeal to religion and the hand of God.”(1)

A point of creation would be a place where science broke down. One would have to appeal to religion and the hand of God. - Hawking

Why did he say that?

Logic requires that just as a woman cannot give birth to herself, so nature could not have given birth to itself. Instead, logic demands that it must be something non-natural, i.e., supernatural. (3)

In an effort to avoid the logical implications foreseen by Hawking, atheist physicist Lawrence Krauss published a book A Universe from Nothing. (4) In it, he attempted to explain how the universe might have come out of something he describes as “nothing”. Some mistakenly understood Krauss’s “nothing” to be absolutely nothing at all, when his “nothing” is actually “something”. So let’s look at both options to see if either works as an explanation for the origin of the universe.

More...

https://www.kirkdurston.com/blog/nothing

******

In the “Mathematical Glory” of the Universe, Physicist Discovered the “Truly Divine”

How did this slip through? John Horgan with Scientific American interviewed a physicist colleague, Christopher Search. The physicist is appealingly direct in rejecting the atheism associated with Stephen Hawking and other venerated names in the field. More than that, he says it was physics that brought him to a recognition of the “truly divine” in the universe:

Over the years my view of physics has evolved significantly. I no longer believe that physics offers all of the answers. It can’t explain why the universe exists or why we are even here. It does though paint a very beautiful and intricate picture of the how the universe works. I actually feel sorry for people that do not understand the laws of physics in their full mathematical glory because they are missing out on something that is truly divine.

The beautiful interlocking connectedness of the laws of physics indicates to me how finely tuned and remarkable the universe is, which for me proves that the universe is more than random chance. Ironically, it was by studying physics that I stopped being an atheist because physics is so perfect and harmonious that it had to come from something. After years of reflecting, I simply could not accept that the universe is random chance as the anthropic principle implies.

More on the anthropic principle and on multiverse theory:

Like string theory, this is not science. How do you test the existence of other universes? The universe is everything out there that we can observe. Another universe would therefore be separate from our own and not interact with it in any manner. If we could detect other universes, that would imply that they are observable by us but that leads to a contradiction since our universe is everything that is observable by us.

The anthropic principle is something I discuss in my freshmen E&M class actually. However, I think it is a total cop-out for physicists to use the anthropic principle to explain why the laws of physics are the way they are. The anthropic principle implies the existence of other universes where the laws of physics are different. But the existence of these other universes is untestable. It also implies that our existence is mere random luck.

At the end of the day, the existence of multiverses and the anthropic principle are really religious viewpoints wrapped up in scientific jargon. They have no more legitimacy than believing that God created the universe.

He came to these conclusions after breaking with “dogmatic” atheism:

I was always curious about how things work. When I was young, physics seemed to offer answers to all of the mysteries of the universe. It felt authoritative and unequivocal in its explanations of nature and the origin of the universe. In that sense it was the perfect religion for my teenage self as I went through an atheist phase, which admittedly was probably provoked by all the popular physics books that I was devouring at that age such as A Brief History of Time. Those books were always so dogmatic like the Catholic Sunday school I went to as a kid.

As it happens, these are all themes that are developed with great rigor and depth in Center for Science & Culture director Stephen Meyer’s next book, The Return of the God Hypothesis.

https://evolutionnews.org/2020/02/in-th ... ly-divine/

I was relaxing one evening when the quietness of the house was destroyed by the sound of a thunderous crash upstairs. Leaping to my feet, I yelled, “What was THAT?”

“Nothing!” was the reply that floated down the stairwell from a person not yet old enough to realize that there are few adults indeed who find such an explanation satisfying.

Strangely, using “nothing” as an explanation has recently been suggested for something much more impressive than a thundering roar on the second floor. I refer to the origin of the entire universe—the biggest crash of all, as it were.

During the course of the 20th century, scientists discovered something that poses a serious philosophical problem for atheism. Cosmologists observed that the entire universe is expanding. The consensus, working backward in time, is that it had a beginning which, of course, raises the question, “What caused THAT?”

Strangely, using “nothing” as an explanation has recently been suggested for something much more impressive than a thundering roar on the second floor.

There appears to be no escape from the reality of a beginning for physical reality, both scientifically (1) as well as mathematically. (2) Although Steven Hawking died an atheist (so far as I am aware), he had the insight to state, “A point of creation would be a place where science broke down. One would have to appeal to religion and the hand of God.”(1)

A point of creation would be a place where science broke down. One would have to appeal to religion and the hand of God. - Hawking

Why did he say that?

Logic requires that just as a woman cannot give birth to herself, so nature could not have given birth to itself. Instead, logic demands that it must be something non-natural, i.e., supernatural. (3)

In an effort to avoid the logical implications foreseen by Hawking, atheist physicist Lawrence Krauss published a book A Universe from Nothing. (4) In it, he attempted to explain how the universe might have come out of something he describes as “nothing”. Some mistakenly understood Krauss’s “nothing” to be absolutely nothing at all, when his “nothing” is actually “something”. So let’s look at both options to see if either works as an explanation for the origin of the universe.

More...

https://www.kirkdurston.com/blog/nothing

******

In the “Mathematical Glory” of the Universe, Physicist Discovered the “Truly Divine”

How did this slip through? John Horgan with Scientific American interviewed a physicist colleague, Christopher Search. The physicist is appealingly direct in rejecting the atheism associated with Stephen Hawking and other venerated names in the field. More than that, he says it was physics that brought him to a recognition of the “truly divine” in the universe:

Over the years my view of physics has evolved significantly. I no longer believe that physics offers all of the answers. It can’t explain why the universe exists or why we are even here. It does though paint a very beautiful and intricate picture of the how the universe works. I actually feel sorry for people that do not understand the laws of physics in their full mathematical glory because they are missing out on something that is truly divine.

The beautiful interlocking connectedness of the laws of physics indicates to me how finely tuned and remarkable the universe is, which for me proves that the universe is more than random chance. Ironically, it was by studying physics that I stopped being an atheist because physics is so perfect and harmonious that it had to come from something. After years of reflecting, I simply could not accept that the universe is random chance as the anthropic principle implies.

More on the anthropic principle and on multiverse theory:

Like string theory, this is not science. How do you test the existence of other universes? The universe is everything out there that we can observe. Another universe would therefore be separate from our own and not interact with it in any manner. If we could detect other universes, that would imply that they are observable by us but that leads to a contradiction since our universe is everything that is observable by us.