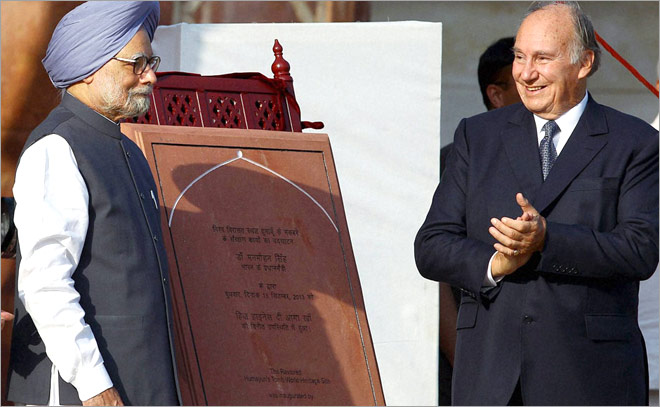

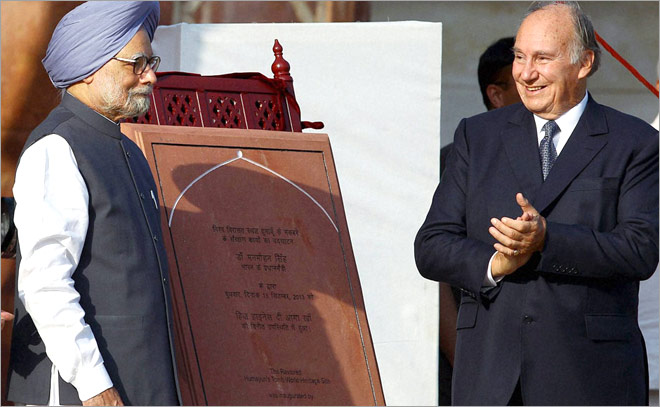

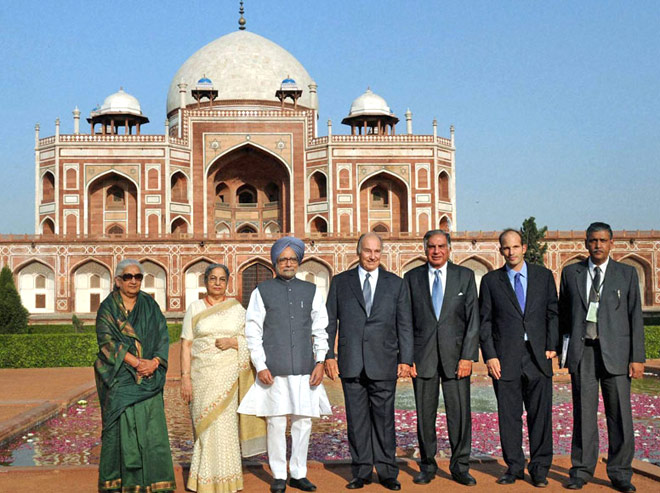

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh unveils a plaque to inaugurate the restored work at Humayun's Tomb as the Prince Karim Aga Khan applauds at a ceremony in New Delhi.

indiatoday.intoday.in/story/aga-khan-what-keeps-him-on-course-with-reviving-cultural-heritage/1/314461.html

Aga Khan: What keeps him on course with reviving cultural heritage in developing world

Sandeep Unnithan New Delhi, October 13, 2013 | UPDATED 20:29 IST

The Fourth Aga Khan, the spiritual head of the Ismaili community, also heads a unique Aga Khan Trust for Culture. The trust which revives monuments and cultural spaces to benefit local communities in Asia and Africa. The Aga Khan was in Delhi recently at the completion of the Humayun's Tomb project. In a rare interview, he spoke to India Today's Deputy Editor Sandeep Unnithan on the completion of this very unique project in the heart of Delhi, what keeps him on course with reviving the cultural heritage in the developing world.

Q: The journey that started with a request by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh at the Humayun Tomb in 2004 has ended here nearly a decade later. Most of the principal characters were back on the same stage. What are your feelings about this project today?

Aga Khan: The development exercise whether in culture or industry or agriculture projects have a timeframe which is between ten and twenty years. These projects take time and they take time before they produce results. The fact that you are talking to a consistent team on the other side is very very important. Particularly when you are doing something which hasn't been done before. If you are doing something which has been done before, you don't need to go through a consultation process but this form of cultural restoration exercise (the renovation of the Humayun's tomb), hadn't been done in this sort of a way in India.

So in my case, it was not only a privilege to have a continuity but it was a very creative dialogue and I mention this on purpose because it was the prime minister who in a speech in AKTC forum talked about public-private partnerships - we haven't heard that before on cultural activities we've heard it before on economic activities, but not on cultural activities.

Q: Was there something on your mind at that moment when he said he'd like you to take that project up on a PPP mode? Was there something in your mind that you wanted to do?

AK: Very much so. We really grateful for this concept and I'll tell you why without going into the details. We have done one small project in another country where we had not negotiated, where we did not agree on post-construction management. We returned the asset to a different management team...we were looking at the post-construction team…we were looking at an environment for the post-construction management of these assets. In fact this is immensely important for the project in Cairo, which is fairly old. If you took a survey of the people who use that project, you will find the one thing that they appreciate is not only the project but the quality of its maintenance.

Q: Is that the most satisfying aspect of this project? The post phase?

AK: Oh no. first of all the possibility of this project to go out of its original scale is very exciting because it has gone from 36 acres to nearly 100 acres. The scale of the project has multiplied by three, so that alone is a very exciting opportunity.

I think the second thing that we learnt on this project, every project we deal with some kind of local environment here we were dealing with a faith community and we needed to have the confidence of the faith community in order for the programme to be a success. Very often the local community have a tradition and a knowledge and experience of the asset and they are sensitive and in this case, Ratish (Ratish Nanda, the AKTC's project director in India) were able to get by - I don't like the word 'by' but whatever you would want to call it.

Ratish Nanda: There is a lot of buy-in your highness, both the government and the local community, hence we had sort of, as someone said, 'got the camel's nose under the tent'.

Aga Khan: There are two aspects: the first of it is the condition of this buy-in because ultimately these projects go back to the people in which the local community is responsible, so their attachment to this project in which they will see their interest is very important.

Q: Do you see this as an inspiration for other projects across the country. You are taking up another project in Hyderabad.

AK: Yes. Absolutely. We are taking up other projects in Hyderabad, more projects were mentioned to us today...discussions are on with various ministries. Essentially what we are talking about is converting dormant assets into productive assets for a local economy or a national economy.

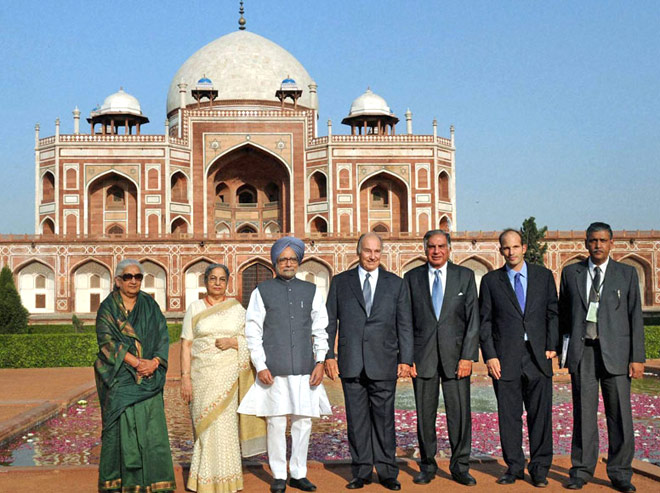

PM Manmohan Singh, his wife Gursharan Kaur, Prince Aga Karim Khan, Chandresh Katoch and Ratan Tata in the unveiling of the renovated Humayun’s Tomb.

Q: How is the project that you are taking up in Hyderabad, the renovation of the Qutub Shahi tombs, Is it similar to this, is it different from the Humayun's tomb?

AK: I don't know whether you want to describe this Ratish.

Ratish Nanda: The project, your highness, is very much derived from a combination of Humayun's tomb and Sunder Nursery. It's the scale of the area we are working on is very similar but the number of heritage buildings which are contained within are significantly larger.

AK: And some of them of them are significantly bigger than what we find in Sunder Nursery. Another aspect is the typology of the buildings that completes the portfolio of Mughal architecture.

Q: Could you explain the concept of the baseline study which you embark on before taking on a project?

AK: The notion of the baseline study is very important in these studies. What we've been trying to do is to convince municipalities, communities that this sort of initiatives are economically very very solid in what they do in terms of people and in order to demonstrate that, you have to have a baseline project which tells you what is the quality of life before, what is the quality of life when you're through…the baseline study has become one of the tools we use to demonstrate to municipalities, to direct donors to govt agencies that this is a restoration process, we are simply not restoring a structure.

Q: What factors do you look into before you pick up a project?

AK: A baseline study would tell us how many people we would hope to impact, in what time, in what ways, so, it will give us, what I would call it, targets in quality of life, numbers of people. It would also indicate to us, what are the fragilities of those communities. Very often, there are very real social problems in those communities and that's the first thing. The second thing is the degree of buy-in they can achieve, because none of the projects in this particular field could survive. It really is a condition. So the local community's attitude is important. The third thing would be our own attitude, do we have the resources? do we have the knowledge? We have multiple aspects in this project, healthcare, education, access to credit, all of this. And I would go so far as to say that probably these projects would not be able to go where they do go if they were single initiatives. They have to be multiple and that, I think is the conditionality.

The fourth one is what I would call it the legislative because these sites are very often complex. There are multiple owners, there are people who have claims, there are trusts, we have to deal with so, there are other ones from the Aga Khan Trusts' point of view, it would be, 'what is the dimension of this activity to other things we are doing?' and this does tend to consume considerable resources.

One of the threats of this program is what they call gentrification. That is, you change the nature of the environment, you bring new value to the assets, people tend to monetize those assets, so they tend to sell, to rent, move to other areas and very often, they don't manage their added wealth very well this process of gentrification is a well-known problem and in fact in Cairo, we had to negotiate to ensure that didn't happen.

Q: India is today richer than it has been in the past but not too many of its wealthy enterpreneurs give back to society. How do you view philanthropy? You had the choice not to do what you are doing.

AK: Its difficult for me to put myself in the position of an Indian entrepreneur. I wouldn't be able to comment on that. I think what drives our network is to enable people to manage their destinies. Once they manage their destinies, you will see, generally speaking, a take-off situation. Its when they cannot manage their destinies and cannot achieve a level of economic independence that they are indebted in a terrible way or are subject to climate change because they are in agriculture or because they are high-risk and they have an earthquak - these are situations which we try to assist. We are not interested in philanthropy in a western terminology as I would call it, because philanthropy or what they call it, charity, is not our notion of development. Our notion of development is to assist people to go from a notion of an unsatisfactory position of development to an autonomous position. That to us, is what is important. Once they are autonomous, our role is finished. They can manage their destiny.

Q: Do you have a favorite story about one of your experiences?

AK: I've been in this for so many years, it would be difficult to pull out individual situations. Generally speaking we have seen a process of change, the inputs that cause change. That is what we look at all time, what are the forces that cause individual societies to change. I think the other thing in the cultural domain is quite exciting, is that these cultural assets are sometimes in rural areas and if we can make those assets productive even if they are much smaller, it helps diversify the local economy. A farmer who has four children will have one child - you start seeing a process of stabilization of family. That for us, is quite exciting.

Q: When you recently spoke at the Aga Khan award for architecture you mentioned the power of architecture to transform lives. Is this what you referred to?

AK: One of the things we have seen over the years is of families in rural areas and urban areas starting to have disposable surplus. And you ask yourself, how do they use that disposable surplus? The first thing they will do is improve their habitation. They will put a metal roof over their house, instead of putting a bamboo roof. They hopefully will separately the water flows so that the cattle will no longer sully the water that they use in the house. They will improve the chimney so that they get smoke out of the hut, and later on, wealthier people still go on doing this, they keep trying to improve their habitat, so our sense is that there is a natural instinct in people to try to improve their living environment. So obviously, we would like to see more. Much of the Muslim world is in the seismic world, from China to the Mediterranean., there is a high concentration of seismic areas, and we're losing many communities due to earthquakes. That's the sort of thing that is cause for worry. During the crisis in Kashmir (the 2005 earthquake) for instance, we tried to assist the people not only during the crisis, but also how they could build better structures, in safer places. That sort of technology is simply not available. So that's the nature of what we're trying to do.

Q: What percentage of your time do the activities of the AKTC consume? Do you keep late hours?

AK: Probably goes into the night. There's a lot of work. I have excellent colleagues in many many fields, but in the end, there is a continuing process of change. There's a whole other dimension to culture. There is the rejection of pluralism. You can see a polarisation of communities, the rejection of people who don't want to live in plural societies and this, to me, is one of the great threats of our times and I think that the IT communications has added to this, because it has projected the individual out of his society and therefore, I would call it, the self interest mode has become more prevalent and I'm worried about this because if you look at the countries that we work in, we're beginning to see more of these conflict and hence culture can help solve this problem by pointing out that in most of the situations, they have an extraordinary inheritance and that inheritance is there, it's a history. It's important that they respect it. Its important that they understand that these previous societies were powerful, they were pluralist and if you look, most of the successful civilizations have been pluralist, they have drawn talent from every community.

Q: In one of your speeches you mentioned a phrase 'Clash of ignorance' as opposed to a clash of civilizations. Could you elaborate on this?

AK: Well, the clash of ignorance, the industrialised socities are not sensitive to different social mores. They're not sensitive to different faith attitudes. Materialism has become a major psychological goal, and that's fine, but, ultimately, people live in society.

Ratish Nanda: Through this conservation effort, the indirect benefit of this project. Many of the women in the Nizamuddin community have earnings upwards of 200 dollars a month, up from zero.

Aga Khan: if you get people to focus on common goals from the future, that would bring people together in rural cooperatives. That is a very attractive way to rebuilding societal forces. And what Ratish is saying is that these cultural projects will help do this.

Q: A lot of your projects are located in minefields around the world.

AK: It is a minefield and I'm not sure you can negotiate it. And ultimately, what you will see is civil society becoming a major force, in many of the civil societies what you are seeing is a major force or post these situations because the strength of these societies causes the civil societies to take root and in a country of Afghanistan, rebuilding civil society is absolutely critical. The problem there is that there is not one civil society, there are many civil societies, because we are talking about different ethnic groups, because different ethnic groups have their own dynamic. Our experience is to work with different groups with civil society. Let it be what it is, don't force change. Once it works with you, it is a wonderful resource. "You have to do it this way - you have to do it that way", by imposing priorities on the rehabilitation. I think in our rural support programmes if we've learnt anything, it is to listen.

Afghanistan was and is a difficult situation. Security was and is a severe problem. To bring security back into the civil domain as opposed to the military domain, is to my mind, a major issue.

Q: How long will it take Afghanistan to stabilize?

AK: I wish I knew the answer, but I don't. There are parts of the country which have moved. There are parts which have remained practically where they are. There are parts of the country which depend on the drug economy, there are parts of the country that are out of that situation. The frontiers are fragile. Therefore we are working in Tajikistan. Were trying to stabilize that. But it's a very difficult issue.

Q: There are many areas of concern?

We have Afghanistan, we have Syria, we were working in Khartoum. We did a lot of work in Mali. The East African coast is unstable today.

Q: Do you wait for stability or do you move in? is it a chicken and egg situation?

AK: There's no rule frankly. We have to work according to the situation. It depends whether the whole country is engaged or partially engaged. It depends on who are the external players. In some situations we simply stop. But there comes a time when it becomes difficult to work.

Q: How do you remember your association with India?

AK: I think about what I used to read about India, China: you remember, the word most used by the western media was 'basketcase'…you know..(laughs) I think over and muse over the stupidity of that word, and how silly it looks today, in relation to India and China. I wonder where the basket is nowadays, probably it is moving to other places. So, in a sense, what we are seeing is an extrodinary process of change in the last fifty years and I try to draw my conclusions from what has been learnt. And I try to understand where situations are going in a sense, creating a national purpose is perhaps one of the most difficult things…and when a country achieves that, it is on a course of self-determination. I've seen a number of countries which have failed to get there…generally younger countries with younger regimes. It takes time to get together. That's a very important issue. The cost of getting there is political, its security, its economics, its all these issues which have to be dealt with together. Ultimately, it is a form that has to be dealt with isn't it. So, Ive seen India mature in a very wise way and its made its place in the international community.

Q: Do you see a contradiction in India being an ancient civilization but a young country?

AK: Not really, because you've invested in education, you've inherited an extraordinary past but you haven't let that freeze you. There may have been forces at one time which may have wanted you to do that but I don't think that is part of the national psyche today…whereas the other countries of the world today-I wont name them-its pretty obvious, they might as well have their eyes at the back of the head rather than in the front. (laughs). In my own community, all these leaders are much younger than I am.

Q: Yours is a very vibrant, pluralistic community. That's a word you use quite often.

AK: Yes, yes, yes. Its helping people to live together to value their diversity rather than to criticize. The Ismaili community is a very international community in terms of its history, its background, languages. Just our religious education is in seven languages and I think the academy will be teaching in many more than in seven languages. We teach 12 to 14 languages in the whole network.

Q: If you were not the Imam of the Ismailis, what would you be?

AK: (Laughs). I would have to think back to when I was a junior in college. That was a long time ago.

Q: Would you have been an architect?

AK: I don't know, I don't know. I was aiming in doing a doctorate in Islamic studies. I was fascinated by the relationships between the Western world and the Muslim world, particularly in Spain. So that would have been my area of doctoral research, but I never got there, not for my own fault, I didn't have a choice. So I really don't know. Generally speaking, when you're doing a doctorate, you become an academic and I don't think I could have become an academic! (laughs) I don't think so.

Read more at: indiatoday