CHIRAGH-I RAWSHAN – AN ISMAILI TRADITION IN CENTRAL ASIA

By:- Mumtaz Ali Tajddin S. Ali

The word chiragh is derived from the Syriac shrag or shragh, meaning lamp, and Chiragh-i Rawshan means shining or luminous lamp, which is one of the oldest surviving Ismaili traditions in the regions of the Central Asia. It is an assembly (majalis) of the believers, where a lamp is illumined, which is its hallmark, and the Koranic verses are chanted for the eternal peace of the departed soul, or for the prosperity of one who is alive.

It appears in the Northern Area of Pakistan that a white cloth is spread on the ground and a lamp (chiragh) is burned in the middle. No other light is allowed to be kept or used as long as this lamp remains burning. The Koranic verses and other religious formula are recited while preparing the wicks of the lamp and inserting the oil made of the fat of sacrificial animal. With loud chanting of salwat, the qadi stands in front of the khalifa (headman) and places the lamp down again three times. It exhorts the Oneness of Divine Light in the universe, but has three relations: the relation to God, the Prophet and the Imam of the age. When the lamp is kindled, the believers deduce that the Imam is the bearer of the living Light of God on earth. It is also known from the rites of Afghanistan and other regions of Central Asia that a piece of salt is put into the pan of the grained wheat (dalda), in which a knife is kept. Then, a certain amount of cotton is put into a pot. Someone picks up the pan in recitation of the salwat and presents to the khalifa. The participants stand up in reverence and the khalifa raises his hands and invokes a prayer of twenty-seven verses. The proceeding is followed by the sacrifice of a sheep, which is called dawati. It should not be lean or skinny. It should be fatty, so that the lamp may be burned from the oil of its fat, called rogan-e-zard. The sheep is thoroughly washed. Then, the khalifa picks up the piece of salt with his left hand and smashes into small pieces with the knife holding in his right hand. He relieves the knife and takes salts and three pieces from the grained wheat and puts on the palm of his right hand, mixing them and passes on to his assistant, who gets the sheep to eat the mixture. The khalifa utters the takbir and his assistant facing towards the qibla, slaughters the sheep. It follows the rite of cotton-making (kar pakhta). The khalifa picks up the cotton and gets it touched to his forehead and prepares a long wick (fatila) for the lamp amidst the chanting of the verses of Chirag-nama. This long wick is folded and the khalifa holds its circle in his finger, who cuts it into respectable pieces. Then, the ghee (rogan-e-zard) is poured into a bowl (chinni). The khalifa puts some ghee in the lamp (kandil), then he drenches all the wicks in the bowl. His assistant takes out the wicks and squeezes to make them ready for burning. Then, the wick is inserted in the lamp and lightened. It is placed in the lantern, which is usually made of a special stone (sang-i sanglej), looking like a ship. The lamp is gray in colour.

A.E. Bertels writes in Nasir-i- Khosrove-i Ismailizm (Moscow, 1959) that it originated in Badakhshan, whose inhabitants were the fire-worshippers and brought it in the Ismaili fold, which seems absolutely incorrect. The oral tradition attributes its introduction by Nasir Khusrao (d. 481/1088) during operation of his proselytizing mission in Badakhshan, but it also cannot be ascertained. Nasir Khusrao used to arrange the assemblies (majalis) in the villages, known as majalis-i dawat. It is however gleaned from different views that the majalis-i dawat later took the present form of majalis-i chiragh-i rawshan.

The word chiragh, dipak, kandil, fanus, siraj or misbah are common terms for the lamp. In Greek, it is called lampas (torch), in German lampein (to shine), in Roman liex or luc (light) and in French lampe or lampas. The lamp was invented in Stone Age about 70,000 B.C., which was a hollow-out rock filled with fat. It was followed by an invention of a pottery lamp, in which oil was burned in Mediterrean regions. Example from about 2000 B.C. have come from Greek rock tombs in Palestine. Sometimes shaped as bird or fish, and it spread in Iran, Africa, Asia and Rome. No lamp was prevalent in Greece till 7th century B.C. The oldest lamp is a shallow stone basin discovered from French Paleotilic. The Hebrew word lappidh also means lamp, and its description is found in the Old Testament: “God commanded that a lamp filled with the purest oil of olives should always burn in Tabernacle of the Testimony without the veil” (Exod. 27:20). The Arabic word misbah (pl. masabih) means lamp, occurring three times in the Koran, once in singular (24:35) and twice in plural (41:12, 67:5). Another word for the lamp is siraj (pl. surujun), occurring four times in the Koran (25:61, 33:46, 71:16 and 78:13). The light of the Prophet is also compared to a luminous lamp (siraj’i munir) in the Koran (33:46). It infers from the Diwan (Cairo, 1933, 1:44) of Ibn Hani (d. 362/973) that each Fatimid Imam was considered to be an emanation of the Divine Light, and numerous epithets described his brilliance and luminousness: al-agharr, al-azhar, al-mutalliq, al-mutadaffiq, al-mutaballij or al-wadda. As the construction of Cairo continued, new mosques would come to be known by names evoking this special quality associated with the Imam: al-Azhar, al-Anwar or al-Aqmar.

After the migration of the Prophet in Medina, the first thing to be done was to build a cathedral mosque. It was constructed on a plot, measuring 54 yards width and 60 yards in length, known as the Prophet’s Mosque (Masjid-i-Nawi). It is said that the palm-leaves (sa’af al-nakhl) were burnt for lightening the interior of the mosque. Qurtubi (d. 671/1272) writes in al-Ta’rif fil Ansab (Cairo, 1987, p. 252) that a Syrian merchant, called Tamim al-Dhari (d. 40/660) brought a lamp (kandil) with oil and wick from his native Syria to Medina and donated for the mosque. His lightening of a lamp in the mosque was an important social event, which was not only approved but also recommended by the Prophet who, gave him a nickname of Siraj (lamp). Thus, the use of lamps at night in mosque became a universal practice among Muslims. The Prophet is said to have permitted a woman, Maymuna to send oil in Jerusalem sanctuary (bayt al-muqadis) in order to light the lamps (Abu Daud, 1:48).

It was a custom of Ali bin Abu Talib to cause his friends to meet him in his house in Kufa and lit a lamp in their midst. Nasir Khusaro reported in his Safarnama (tr. W.M. Thackston, New York, 1986, pp. 55-58) a widespread use of lamps, made of brass and silver in the holy places of Hebron, Bethlehem and Jerusalem. He further noted that the lamp oil, called zayt harr was derived from turnip seed and radish seed. He also wrote that in the mosque of Cairo, there was a huge silver lampholder or chandelier with sixteen branches, each of which was 1½ cubits long. Its circumference was 24 cubits, and it could hold as many as seven hundred odd lamps on holiday evenings. The weight is said to be 25 kantars of silver, a kantar being 100 rotls, a rotl being 144 silver dhirams. More than a hundred lamps were kindled in the mosque of Cairo every night. On the north side of the mosque was a bazar Suq al-Kandil (lamp market).

When Imam Muhammad al-Bakir died in 114/733, his son Imam Jafar Sadik ordered to lit a lamp in the house (al-Kafi, 3: 25). The tradition also indicates that a lamp was also kindled in the house when Imam Jafar Sadik died in 148/765. It is probable that the adherents would have started the practice in their regions.

It is yet indeterminable point, how and when this obscure rite entered into the Ismaili tradition?

In India, the three centuries of Muslim rule (603-933/1206-1526), generally known as the Sultanate period, witnessed the rise and fall of five dynasties: the Slave (603-690/1206-1290), the Khaljis (690-720/1290-1320), the Tughlaqs (720-816/1320-1413), the Sayeds (816-855/1414-1451) and the Lodis (855-933/1451-1526). Then, the Mughal empire was founded in 933/1526. Qutbuddin Aibak (d. 607/1210) was the first Turkish king of the Slave dynasty in India, whose armies had evolved and developed in Persian lands, and consequently the Pesian stamp was very deep upon them. The armies were modelled on the armies of the Persia with the same arms, equipment and tactics. The slaves of the imperial household maintained the Persian tradition in Delhi. These Turks, in their social life also followed the Persian customs, etiquettes and ceremonials. The old Persian customs of zamindos (ground kissing) was also introduced. India specially provided benign climate to the festival of Shab-i Barat, which was festivated for four days.

Shab-i Barat (night of quittancy) is a popular fete among the general Muslims, which takes place on the 14th of the month of Sha’ban. Its native land is Iran, and the Slave dynasty brought and spread it in Indian soil, where the people very rapidly found it coherence in their own tradition. On this day, the people assemble and make offerings of bread, sweet rice, halwa and flasks of water and offer prayers and intercessions for the departed souls. According to Muslim Festivals in India (Paris, 1831, tr. W. Waseem, New Delhi, 1995, pp. 76-77) that the people kindle lamp (chiragh) and recite the following prayer, known as the Fatiha Chiraghan:

“O God, through the merit of the light of the apostolate, our Lord Muhammad, may the lamp that we burn on this holy night, be for the dead a guarantee of the eternal light which we pray to you for. O God of ours! Deign to admit them in the room of unchanging felicity”

Having expressed the above intention, they recite the first and the 102nd chapters of the Koran. This ceremony lasts for three days. There was a popular custom also to send lamps to the mosque, vide I’jaz-i Khusaro (Lucknow, 1876, 4:324) by Amir Khusaro (d. 820/1325).

The festival of Shab-i Barat fostered and dressed in Iran, and then introduced in Afghanistan and India also under the name of Fatiha Chiraghan during the 12th century, and it is possible that the Ismailis of Afghanistan had certain proctivity towards it. Thanks to an oral tradition in this context shrouded in mist for centuries in Tajikistan, which is a key to solve the complications hitherto remained unsolved. The tradition has it that an Ismaili, called Taj Mughal (d. 725/1325) of Badakhshan was deadly against the festival of Shab-i Barat. Instead, he transformed the local traditional assembly, called majalis-i dawat into a specific rite in the house, where a death took place. In the midst, a lamp was kindled and the Koranic verses and the qasida of Nasir Khusaro were recited. This was an original form of the presently known ceremony of chiragh-i rawshan. The selected qasida were reserved for it, whose collection later became known as the Chirag-nama, which is traditional more and historical less. We should however not ignore that the thought of majalis-i dawat was originally propounded by Nasir Khusaro about two hundred years before the advent of Taj Mughal.

Taj Mughal was an origin of Badakhshan, where he had given shelter to Shah Ra’is Khan of Trakhan dynasty of Gilgit and Hunza. Shah Ra’is Khan embraced Ismailism and married to the daughter of Taj Mughal. After some years he persuaded Taj Mughal to occupy Gilgit. Thus, he mustered a sizable force and conquered Chitral at first, then Yasin, Koh Ghizr and Puniyal were subdued. He entered Gilgit, ruled by Torra Khan (d. 735/1335), who submitted and accepted Ismaili faith. Shah Ra’is Khan became the ruler of Chitral, where he founded the Ra’isia dynasty and promulgated Ismailism. It was at this time that the Ismaili faith penetrated in Gilgit, Hunza and Chitral with the indescribable efforts of Taj Mughal. He is said to have proceeded to Sikiang through Pamir. The historians have described an extensive territory under his domination. On the north greater part of Turkistan, on the west the whole area including the city of Herat, and on the south-east right upto the border of Chitral. It implies that when the rite of chiragh-i rawshan was in its formative stage, Taj Mughal spread it in most parts of the Central Asia. The veracity of this tradition however cannot be substantiated from the extant sources, nevertheless, it cannot be brushed aside as untrue. Whether historically true or not, the above tradition embodies certain grains of truth.

In the course of its evolution, the ceremony was reserved for a long time only for the dead person, and was performed not on the night of 14th Sha’ban. It is also likelihood that the reason for giving it the ceremonial name of chiragh-i rawshan was to distinguish it with the rite of the Shab-i Barat, known as the fatiha chiraghan.

The chiragh-i rawshan was not emanated from Shab-i Barat, but exercised a safeguard against it. Neither the fireworks are conducted, nor the graves are venerated, and also no specific time is fixed for it. Later, it was divided in four different assemblies (majalis), namely dawat-i fana, dawat-i baqa, dawat-i safa and dawat-i raza. The last two majalis are now not prevalent.

Majalis-i dawat-i fana

It almost resembles the practice of the ruhani majalis prevalent in the Indian tradition. When one dies, his family members and relatives assemble in his house for three days, known as the dawat-i fana. His family does not cook food for three days, but only a lamp is kindled. Major J. Biddulph writes in Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh (Karachi, 1977, p. 123) that, “On the evening of the appointed day, a caliph comes to the house, and food is cooked and offered to him. He eats a mouthful and places a piece of bread in the mouth of the dead man’s heir, after which the rest of the family partake. The lamp is then lighted, from which the ceremony is called “Chirag Roshan,” and a six-stringed guitar called gherba being produced, singing is kept up for the whole night.”

The dawat-i fana exhorts that when a believer dies, it is his physical death not spiritual. His soul quits the earthy body and assumes celestial body (jism-i falaki). He was a dark himself on earth, but now he becomes light. The brightness is thus eluded symbolically in the lamp. There is a separation among bodies, but not in the light. There is nothing except union in the light after death. It emanates in another interpretation that the fire denotes ardent love and its light is the knowledge, therefore, unless a believer burns in the fire of love with Imam, the light of knowledge is not sparked in his heart. It will be interesting to note that Missionary Muhammad Murad Ali Juma (1878-1966), known as Bapu died in Bombay on February 4, 1966. In his message of February 14, 1966, the Imam said: “I grieved greatly the loss of one of my most devoted spiritual children. His services were above reproach and he was a Candle of Light and example to my jamats.”

Majalis-i dawat-i baqa

The chiragh-i rawshan is also solemnized for the longevity, prosperity and blessing of a person who is alive, known as dawat-i baqa. It also corresponds with the Indian tradition of the hayati majalis. It also exhorts that the Imam is an Everlasting Guide and Epiphany (mazhar) of God on earth. The believers must kindle the lamp of Divine Light in their hearts. Imam Sultan Muhammad Shah also said, “The lamp of the Divine Light exists in you and your hands. This is spoken metaphorically. This lamp always exists in you all” (Zanzibar, 13/9/1899).

This assembly’s purpose is also to reflect upon the unique wisdom of the ayat al-misbah (the lamp verse) of the Koran (24:35), in which God has compared His Light with a lamp. On that occasion, the person seeks forgiveness of his sins, and resolves to lead a virtuous life.

The tradition of chiragh-i rawshan deeply influenced the religious and social life of the Ismailis. It executed an ideal platform of the Ismailis for centuries, who were scattered in different villages of Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Northern Areas of Pakistan and other regions of Central Asia. It reflects an illustration of impermeable unity of the Ismailis in past.

It is said that an Ismaili dai of Badakhshan, called Sayed Yakut Shah visited Iran in 1253/1837 to see Imam Hasan Ali Shah in Mahallat. The Imam is reported to have accorded him permission to launch proselytizing mission in Gilgit and Hunza, including retention of the tradition of chiragh-i rawshan.

Pir Sabzali (1884-1938) had been in Badakhshan during his travel in Central Asia in 1923. He participated the majalis-i chiragh-i rawshan in a village, and seriously noted the defective content of the Chirag-nama being recited in its rites. He pointed out and promised to provide them its approved copy from the Recreation Club Institute. Later, a good copy was sent in 1924 from Bombay.

It is still practised with same spirit, vein and devotion. Muhammad Jamal Khan (1912-1976), the Mir of Hunza had written a letter to the Imam on September 4, 1965 regarding the fate of chiragh-i rawshan. In his reply of September 30, 1965, the Imam declined the request submitted to abandon the tradition of chiragh-i rawshan.

CHIRAGH-I RAWSHAN – AN ISMAILI TRADITION IN CENTRAL ASIA

-

star_munir

- Posts: 1670

- Joined: Tue Apr 22, 2003 12:55 am

- Contact:

‘Ismaili-Sufi and Ismaili-Twelver Relations in Badakhshan in the Post-Alamut Period: The Chiraagh-naama’

Introduction

In 1959 Wladimir Ivanow, the pioneer of modern Ismaili studies,published the text of the Chiraagh-naama in the Revue Iranienned’Anthropologie In the introduction to the published text, Ivanow briefly discusses Ismaili-Sufi relations. Expressing his joy at finding this valuable source that allowed him to elaborate his proposed theory of Ismaili-Sufi relations, he remarks:

I was therefore very glad when some pilgrims from CentralAsia brought a very interesting document, fully vindicating the proposed theory. It is called 'Chiragh-Nama,’ an opuscule of what may be called the purely darwish nature. It may be explained that wandering religious mendicants, who go under the general name of darwishes in the Islamic world, vary very much in their ways, habits and traditions.

According to the local oral tradition the performance of the ritual of Chiraagh-rawshan, lighting or kindling the lamp, was passed down from generation to generation and is linked to the figure of Nasir-i Khusraw (394–481/1004–1088), who is known in the region as Pir Nasir or PirShah Nasir-i Khusraw. The oral tradition draws our attention to the traditions of Chiraagh-rawshan and madaa-khaani , which were an integral part of religious assemblies. The tradition of madaa-khaani , singing devotional and didactic poetry, is as old as the tradition of Chiraagh-rawshan and, in many cases, these two traditions are intimately connected.

The article can be accessed at:

https://www.academia.edu/43189143/_Isma ... view-paper

Introduction

In 1959 Wladimir Ivanow, the pioneer of modern Ismaili studies,published the text of the Chiraagh-naama in the Revue Iranienned’Anthropologie In the introduction to the published text, Ivanow briefly discusses Ismaili-Sufi relations. Expressing his joy at finding this valuable source that allowed him to elaborate his proposed theory of Ismaili-Sufi relations, he remarks:

I was therefore very glad when some pilgrims from CentralAsia brought a very interesting document, fully vindicating the proposed theory. It is called 'Chiragh-Nama,’ an opuscule of what may be called the purely darwish nature. It may be explained that wandering religious mendicants, who go under the general name of darwishes in the Islamic world, vary very much in their ways, habits and traditions.

According to the local oral tradition the performance of the ritual of Chiraagh-rawshan, lighting or kindling the lamp, was passed down from generation to generation and is linked to the figure of Nasir-i Khusraw (394–481/1004–1088), who is known in the region as Pir Nasir or PirShah Nasir-i Khusraw. The oral tradition draws our attention to the traditions of Chiraagh-rawshan and madaa-khaani , which were an integral part of religious assemblies. The tradition of madaa-khaani , singing devotional and didactic poetry, is as old as the tradition of Chiraagh-rawshan and, in many cases, these two traditions are intimately connected.

The article can be accessed at:

https://www.academia.edu/43189143/_Isma ... view-paper

Chiragh-i Roshan, a ceremony of light, was established by Nasir-i Khusraw

Chiragh-i Roshan, a ceremony of light, was established by Nasir-i Khusraw

Posted by Nimira Dewji

Literally meaning “luminous lamp,” the Chiragh-i Roshan (or Rawshan) is a ceremony practised by the Nizari Ismailis of Afghanistan, Tajikistan, western China, and northern Pakistan. The ceremony, generally performed on the third night following the death of a family member, is guided by the authorised text Chiragh-nama which comprises poetry, supplication, and verses of the Qur’an, culminating in the kindling of light. The ceremony emphasises divine light as expressed through Prophethood and Imamat.

Fatimid lanterns on display at the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo. Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica

The ceremony is also performed for celebration such as on the occasion of Id when the community gets together and the principles and values are reinforced, the pivotal one being a collective expression of allegiance to one authority, the present living Imam.

The lighting of the lamp begins with the Qur’anic verse:

O Prophet, verily We have sent you as a witness and a bearer of glad tidings and a warner, and as one who invites to Allah by His command, and as a lamp brilliant (33:45–46).

While the lamp is burning a long poem glorifying the divine light is recited, each verse ending with the salwat:

The Qandil (candle) of the lamp which belongs to Mustafa, the Prophet,

The Light of Allah, the wa al-Duha, the splendour (Q 93:1)

Recite constantly this prayer: Whole heartedly recite Salawat on Mustafa.

Another verse states:

(O Prophet!) You returned from Mi’raj (celestial journey)

With the light of brilliance and crown;

The world is in need of you

Salwat be on Muhammad.

The poem continues with an explanation of how the light of the Prophet

continued in the Ismaili tradition as the light of Imamah and ends with the following

verse:

This line of Imamat

Is established till the Qiyamat (Day of Judgement)

For the salvation of the ummat (Muslim Community)

Salawat be on Muhammad.

The Chiragh-i Roshan was established by Nasir-i Khusraw in the eleventh century as representative of the Fatimid Caliph-Imam al-Mustansir bi’llah I (r.1036-1094) in Central Asia. Ismailis of these regions, under Soviet rule, faced enormous challenges in practising their faith, including the inability to have regular contact with the Imam of the time. Nasir-i Khusraw’s writings, teachings, and the ceremony of the Chirag-i Roshan enabled the community to preserve their faith.

The numerous Ismailis preachers and teachers who followed Nasir-i Khusraw in the region never overshadowed his role and status in the eyes of Central Asian Ismailis. He remains a role model for them in terms of knowledge, spirituality, dedication, ethical standard, and loyalty to the Imam of the time.

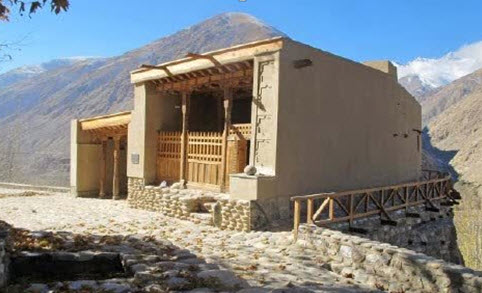

Nasir-i Khusraw’s shrine at Hazrat‐e Sayyed, Afghanistan restored by Aga Khan Trust for Culture Source: Archnet

Adapted from Mir Baiz Khan’s Chiragh-i Roshan: Prophetic Light in the Isma’ili

Tradition

https://nimirasblog.wordpress.com/2022/ ... i-khusraw/

Re: CHIRAGH-I RAWSHAN – AN ISMAILI TRADITION IN CENTRAL ASIA

The word 'Shab' has Persian origins, meaning night, while 'Barat' is an Arabic word that stands for salvation and forgiveness. On the night of Shab-e-Barat, Muslims worldwide ask for forgiveness for their sins from Allah.

This festival is marked with great enthusiasm across South Asia, including countries like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Central Asian countries such as Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan.

Many believe that this is a holy night when Allah is more forgiving and that sincere prayers can help wash away their sins. The night is also used to seek mercy for deceased and ill family members, and it is believed that Allah decides people's fortune for the year ahead, their sustenance, and whether they will have the opportunity to perform Hajj (pilgrimage).

Further, Shab-e-Barat has its unique traditions, depending on cultural diversity and local traditions. During the day, Muslims prepare delicious sweets like Halwa, Zarda, and other delicacies to distribute among their neighbors, relatives, family members, and the poor. Many visit the graves of their loved ones to pray for eternal peace for their souls. Some also observe a fast on Shab-e-Barat.

This festival is marked with great enthusiasm across South Asia, including countries like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Central Asian countries such as Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan.

Many believe that this is a holy night when Allah is more forgiving and that sincere prayers can help wash away their sins. The night is also used to seek mercy for deceased and ill family members, and it is believed that Allah decides people's fortune for the year ahead, their sustenance, and whether they will have the opportunity to perform Hajj (pilgrimage).

Further, Shab-e-Barat has its unique traditions, depending on cultural diversity and local traditions. During the day, Muslims prepare delicious sweets like Halwa, Zarda, and other delicacies to distribute among their neighbors, relatives, family members, and the poor. Many visit the graves of their loved ones to pray for eternal peace for their souls. Some also observe a fast on Shab-e-Barat.